Almanda Siméon was an orphan, nomad, hunter, artisan, avid reader, and the resilient great-grandmother of Innu writer and journalist Michel Jean. Kukum, beautifully translated from the French by Susan Ouriou, is inspired by the story of Almanda’s life, which spanned almost a century.

Almanda was raised by a couple she refers to as her aunt and uncle in the small town of Saint-Prime. One evening, an encounter with a young Innu named Thomas Siméon completely changes the course of her life. They fall in love fast; they marry young. She joins the Siméon clan and starts travelling with them across Pekuakami (Lac Saint-Jean), up the Peribonka River to Passes-Dangereuses, a territory defined by its waterfalls, where they spend winters. She learns how to hunt and survive in the cold and in the wild. She learns the language and traditions of her new family. She becomes a “real Innu woman.”

Told from a first-person point of view, Kukum is in many ways a love story. Just as Almanda falls head over heels for Thomas, so too does she with the lands he inhabits and the Innu way of life. Jean writes: “Happiness is something that is hard to define. But happiness is what I felt at that moment, in the canoe I shared with Thomas, surrounded by our people, looking out onto the lake. Our lake.”

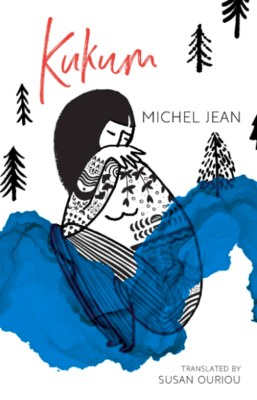

Kukum House of Anansi Press

Michel Jean

Translated by Susan Ouriou

$22.99

paper

224pp

9781487010904

Eventually, the nomadic life adopted and adored by Almanda Siméon is taken away from her, her husband, and her children. The lumber industry invades their traditional route, blocking the river and the way to Passes-Dangereuses. They’re forced to stay in the community of Pointe-Bleue (the First Nations reserve of Mashteuiatsh). The rest, as we say, is history. Sedentism doesn’t agree with them. Residential schools, dependence, substance abuse, language loss – Jean traces all of it to the moment his people were sent away from the forest.

Kukum is an admirable book. Jean makes us feel the loss experienced by Quebec’s Innu community through a highly personal story. With Almanda as a narrator, the reader discovers and falls in love with Innu culture, just as she does. The growing immersion into their world makes the eventual tragedy of its loss that much more heart-wrenching.

Jean refers to this book as a work of fiction based on his great-grandmother’s version of facts. There’s no one to corroborate that she actually trekked to Quebec City and sat in Maurice Duplessis’ office for days until he agreed to hear her complaints about drunk drivers in Pointe-Bleue. Fact or fiction, Kukum bears an undeniable historical backbone that would make it a worthy addition to any Canadian high school or college curriculum.

Beyond lessons about the past and present of the Innu, Jean teaches us that loss of land and culture has a universal impact. His great-grandmother believed that life is a circle, and that destruction will always come back to haunt the destructor. Kukum serves as a reminder to listen to your elders, heed the lessons of the past, and question what is done in the name of progress. In the end, after ninety-seven years of hardships and struggles, what Almanda worried about the most was the world left behind for her great-grandchildren.mRb

0 Comments