Richard Tardif showed up for his first day of work at the Eastern Door, a Mohawk community newspaper at Kahnawake, just across the Mercier Bridge from home in Lachine, in a “suit and tie, notebook and voice recorder in hand,” chewing on some big questions: “Why the heck was I here; among the Mohawks, in Kahnawake? What business did a Canadian reporter have reporting in Kahnawake, a Native community?”

Tardif came out of Concordia’s journalism program after a military stint and a security job in downtown Montreal. A short internship led to six years as a full-time reporter at the Eastern Door.

He quit, asking himself where he was going next because he wasn’t sure where he’d been. “I was uncertain about on which side of the river I belonged. Why was I in such limbo? It took an examination into the perspectives of cross-cultural reporting to find my answer.”

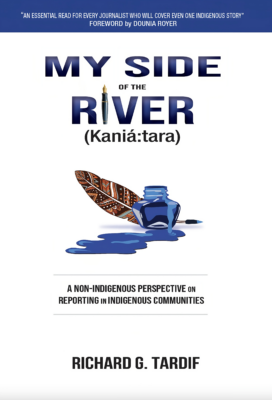

My Side of the River Smiling Eyes Press

A Non-Indigenous Perspective on Reporting in Indigenous Communities

Richard G. Tardif

$14.95

paper

154pp

9781778014130

Tardif admits, “I don’t have a clue about Native People,” except the few individuals he’s met in the military, working security at Woolworths, or as a prison guard. “I lacked empathy watching the Natives and also non-natives, spending their welfare cheques,” he writes. “They were lumped into one category – Canada’s Indians, easy to fool, easy to get drunk, easy to criticize.”

Unfortunately, not much happens with this implied journey as a journalist, because the book takes a left turn and never comes back.

It becomes a rehash of old stories that the author covered, and some he didn’t, while working as a white journalist stuck in a cultural rut. A drunken Cree father in northern Saskatchewan is charged with abandoning his two children to die in a freezing blizzard. The father pleads guilty to criminal negligence causing death. Tardif questions whether Indigenous “sentencing circles,” the community’s choice, are valid alternatives to prison, but without any historical, cultural, or statistical context. Idle No More and the UN’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) – major Indigenous rights stories – are dismissed with a shrug. A story of Innu people protesting the impacts of low-flying NATO jet flights in Labrador seems to begin but leads nowhere.

Stories about the Mohawk at Kahnawake are about clashes with the province and police over taxes, tobacco, and cheap gasoline. More stories about Iroquois (Mohawk) passports; eviction letters sent to mixed (Mohawk and non-Indigenous) couples by the Kahnawake band council; disputes with a Quebec union over who gets the jobs to repair the Mercier Bridge.

These are stories about grinding areas between nations and cultures, governments and jurisdictions, different peoples with different histories and values. Yet the author seems unwilling or unable to explain why it matters to readers.

Also, what happened to that personal journey implied by the title, dangled in the introduction, and teased on the book’s back cover?

Lessons from a white journalist covering an Indigenous society aren’t there. Even Tardif’s use of the word “Natives” throughout, a term replaced by more acceptable terms like “Aboriginal” (1980s) and “Indigenous” (since 2000) indicate resistance to even a basic change of terminology.

A telling sentence is found near the end of the book.

“In my time in Kahnawake… I began to see myself transforming into a Native journalist, losing some objectivity.”

As though only white journalists can be objective, and this somehow becomes the symbolic river that Tardif decides he will not cross.mRb

0 Comments