Time, in the way that we experience it, in the way that we feel it, is not linear. It’s totally elusive: one hour can stretch into eternity, while certain days pass in the blink of an eye. What is the present? It’s a time-space that’s always happening but almost impossible to stay inside of: a hungry monster constantly chewing on the future and turning it into a haunting memory.

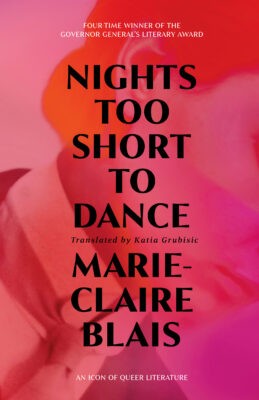

Nights Too Short to Dance

Marie-Claire Blais

Translated by Katia Grubisic

Second Story Press

$22.95

paper

260pp

9781772603507

René’s aging transgender body forms the nostalgic axis of the book. Once a chic and vivacious part of Montreal’s queer nightlife, René’s late-night piano-playing days are over, as well as his passionate forays into activism. The novel’s narrative poetry forms around him in a pool of reminiscence as he sits in his grand old home surrounded by dusty books. Visited in memory by a constant stream of friends and lovers who appear in the intensity and beauty of their youth, René is never really alone. At the end of the book, the characters that inhabit his fantasies slip into reality. Louise, Johnie, Gerard I, Gerard II, Lali, Doudouline, Polydor, and l’Abeille, all of his favourite girls, arrive in their own age-ravaged flesh to cheer up the sickly René.

The novel’s perspective, while centered around René, is not anchored there. Often we enter the minds and experiences of others, learning incredibly intimate facts about their unique lives. Doudouline has an actress mother who she both worships and feels belittled by. Gerard I does not have her mother, and fills the void with a spiralling addiction problem. Lali, from Berlin, is haunted by memories of a house that burned down on top of her family, and Johnie’s sister has disappeared. Blais seamlessly moves between these perspectives, occupying a vantage point that is at once personal and omniscient, as if the group shares one complex and varied mind or soul.

The solidness of bodies, the physicality of them, is a central problem in the novel. René sometimes feels trapped in his body, an imperfect and expiring flesh-prison that holds his eternal, masculine soul. He longs for “a perfect birth in a body that fits perfectly,” and is frustrated with his inability to move, to waltz out into the city-night with a girl or two on his arm. Louise’s body betrays her in another way: cancerous cells eat her from the inside out, forcing her to chop off parts of herself to survive. And Gerard I’s body weakens and eventually perishes in the wake of the chemicals pulsing through her veins. Gerard II (whose given name is Teresa) adopts the former’s name in respect, as a way to ensure that Gerard I lives on. Curses and blessings are passed down through family lines, and reincarnation is an idea much repeated. Blais’ characters ask us: what if the body is less fixed than we have been made to believe? Perhaps two souls can share the same body, or multiple bodies can share the weight and pain of one soul.

Nights Too Short to Dance is a poetic rumination on what it means to live. Blais reminds us, in her novel filled to the brim with love, of the agonizing fleetingness of life: to love is also to make yourself vulnerable to loss, and to feel loss is to know that you have once loved.mRb

0 Comments