“How do you want to die?”

This question was posed to Adam Leith Gollner at a recent talk by a gruff Bostonian in a Hawaiian shirt with grey hair slicked back “gangster-style” and an oversized watch.

“And it wasn’t said like ‘If and when you do die, how would you choose for it to happen?’” Gollner says. “It was more like this murderer standing over you, saying ‘Pick your way.’ It was such an antagonistic statement.”

It seems that when you’re the author of an in-depth treatise on the subject of eternal life, things can get a little personal.

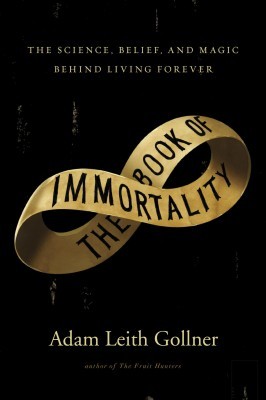

Gollner’s latest publication, The Book of Immortality, is a sweeping, eclectic examination of a few of humanity’s deepest obsessions. From the fountain of youth to the eternal soul to the concept of “singularity,” in which we will merge our consciousness with computer intelligence to become infinitely powerful divine beings, Gollner examines our ability and need to imagine life after life.

The Book of Immortality

The Science, Belief, and Magic Behind Living Forever

Adam Leith Gollner

Doubleday Canada

$29.95

cloth

416pp

9780385667302

Gollner also comes in contact with a wildly diverse set of beliefs and practices, including those of immortalists, several of whom were present at the same talk as the steely Bostonian. Immortalists, as we discover, are people who believe that death is not the natural and unavoidable outcome of life, but rather a bad habit – one that can be kicked.

“They find the idea that death is inevitable to be offensive,” Gollner tells me. “They speak of death as this ism like sexism or racism, this backwards way of thinking that needs to be eradicated.” Expressing his own belief – that death comes for us all – was enough to raise the hackles of more than one immortalist.

“Their belief system that death is not real is one of the most warping things to me,” Gollner says. “What an alien mindset. It hurls you into this place where nothing you know is real; your way of making sense of the world is being challenged. And when you’re in that place of uncertainty, well, the mind doesn’t like that. We’ve entered into the cesspool of belief.” But Gollner gamely straps on his hip waders and sloshes around in that cesspool, spending many pages grappling with situations where logic has clearly left the building.

Early in the book he visits St. Augustine, a Florida town that claims to be the home of the “genuine” Fountain of Youth, found by Ponce de Léon in the sixteenth century. What ensues, as Gollner tries to verify the fountain’s authenticity, is a regular maelstrom of contradictions, logical fallacies, spurious reasoning, and straight-up magical thinking. In one passage, he asks the fountain’s media spokesperson, Michelle Reyna, if Ponce de Léon really discovered the fountain in St. Augustine. Reyna replies:

Absolutely. Although some people claim he may not have made it this far north. We agree to disagree with those people. In either case, because this is known as the Fountain of Youth, and it has been here for over one hundred years, we’re going to say that he was here, because no one else is taking the lead on it. If no one else can produce any evidence that he landed elsewhere, then why not?

Later, Reyna points out some Spanish moss, which she then informs Gollner “is not Spanish, and it is not moss.”

The mental gymnastics needed to follow Reyna’s reasoning are, in fact, only a warm-up for the rest of the book. By definition, Gollner’s subject evades easy understanding. He tells us early on that immortality is unknowable and inconceivable, and then goes on to spend four hundred pages trying to know it and conceive of it. The Book of Immortality is, in a way, a creative non-fiction account of one man’s attempt to drive himself crazy by confronting the unconfrontable.

“‘Huge mindfuck’ is an apt description of what [writing the book] was like,” Gollner tells me. “I barely remember, to be honest. I remember being grateful when I came across the description of immortality as a preoccupation resistant to articulation, and feeling like, oh yeah. There are breakthroughs in terms of understanding what you cannot understand.”

Belief is really the linchpin of his research, the itch Gollner returns to over and over and can’t quite scratch. The longer you spend in the book, the more you become attuned to your own inclinations toward convenient suspensions of reason. I might chuckle or cringe at men having goat balls implanted in their scrota to ramp up their sex appeal, but hey, I’m writing this by the light of a Himalayan salt lamp. I don’t have a leg to stand on. What unites Gollner’s various narrative threads is this universally human ability to put faith in something outside of our understanding, whether it be a supreme being or an eight-thousand- dollar jar of skin cream. Some of these leaps of faith are numinous, sublime, while others have a strong whiff of snake oil, but the principle is the same: we want to believe. And there’s something compelling, and charming, and scary, about absolute credulity, even – or especially – when it comes from those on the fringes of what’s acceptable to believe in.

Curiously, although nearly everyone in this book is obsessed with living forever, or at least radically extending their lifespan, only a few talk about why, or what they would actually do with their bonus years. Gollner muses that life eternal, at least life as we know it, might not be quite the garden of delights the immortalists imagine. “Borges said something like prolonging man’s life means prolonging his misery,” he says. “I don’t think about it that starkly, but it does mean prolonging reality. And reality is good and bad. Like, if we live forever, will we have to work menial jobs forever to support ourselves? Would I want to write books forever? Like, actually forever?”

Gollner recounts his response to the floral-clad Angel of Death he encountered in Boston. “Just to be clear, I don’t want to die,” he told the guy, and the audience, and me. “I accept the fact that it’ll happen, but I don’t want to invite it. Don’t kill me, if that’s what you’re saying. And if you have to kill me, please do it in my sleep. There’s a difference between accepting that death is real and wanting to die.”

“I’m not on a death trip,” Gollner tells me, serious and unironic. “I like to think of myself as being on a life trip. A journey of life.” mRb

0 Comments