October 1970. Montreal. The kidnapping of James Cross, the murder of Pierre Laporte, the nation watching as Trudeau orders troops into the streets to search for FLQ terrorist cells. We know the story.

Or do we?

Louis Hamelin, in this peerless translation by Wayne Grady, tells another version through the eyes and words of Samuel Nihilo. Sam learned the uniquely Quebecois intellectual métier of investigative poetry at the knee of Chevalier Branlequeue, a grizzled separatist publisher. The latter holds court at the Lavigueur Taverne on Ontario Street where his group meets to discuss key FLQ members and decode the texts of newspaper articles published during the crisis. (Can’t you taste the Molson and feel the Export “A” smoke absorbing into your skin?) His mentor’s death leaves Sam in possession of Chevalier’s FLQ crisis files and plunges him into a world of conspiracy.

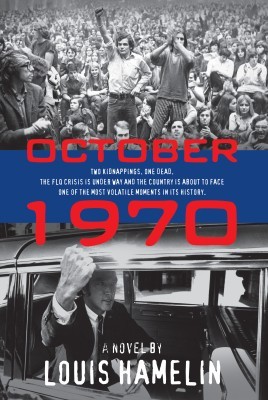

October 1970

Louis Hamelin

Translated by Wayne Grady

Arachnide

$24.95

Paper

600pp

978-1-77089-103-6

Sam flees the past, to a cabin in Abitibi, raising chickens and screwing his barmaid girlfriend, who is also lead actress in a theatre company that stages Camus plays for the mill town rubes. The conspiracy haunts Sam, as does an apparition of Laporte and a lynx just like the one he saw a trapper strangle with his bare hands when he was a boy. The book’s original title was La constellation du lynx. In the animist pantheon, the lynx represent secrets, and constellations speak to the human tendency to project shapes and meaning onto abstract points. Do we see a secret or do we see what we want to see?

Novels whose plots consist of a big reveal have the same structural challenge in that making an entire work point to something hidden, and then finally showing it, can be anticlimactic. Hamelin’s expository devices are primarily didactic, but the burlesque pacing of the uncovering keeps the reader interested throughout the book’s six hundred pages, although there is some begging of the point at the end. What’s the conspiracy? (Spoiler alert!) The FLQ had been infiltrated by agents provocateurs – the SQ, RCMP, Canadian Military, and even the CIA knew what was going on the whole time and could have stopped it earlier, but they let the events escalate so that they could justify sending troops into Quebec to intimidate the nascent separatist movement. The story is told as fiction, however Hamelin adds one single footnote to say that a particular story from the police round-up is likely apocryphal; does the single authorial incursion imply that the rest of the anecdotes are factual?

If this novel is to be taken as histoire masquée then it has revisionist or apologist intentions. FLQ members are mainly portrayed as sympathetic characters whose crimes are explained with a boys-will-be-boys wink. Whether led astray by provocateurs or not, these weren’t kids who chucked a brick through the school window on a dare – the cell members held hostages for months, set bombs, robbed banks. The book’s villains are police, army, and the agent provocateurs, especially Yves Langlois, who is renamed Francois Langlais for the novel (tongue-in-cheek, one hopes).

October 1970 is a marvellous work. Perhaps it’s the current political climate, but in brushing aside FLQ brutalities to replant heirloom seeds of indignation over the Saint-Jean-Baptiste day riots and the War Measures Act, it feels almost like a separatist book of Exodus – persecution waxing poetic to establish moral authority for the chosen ones. For those of us who experienced the FLQ crisis from elsewhere in Canada, the story educates, entertains, and provides important insight about the formative years of the generation that drives separatist politics. No matter what you call it, October 1970 is one of the most important reads of recent memory and could perhaps even be considered the Quebecois answer to Two Solitudes. mRb

0 Comments