The subtitle of Shelagh Plunkett’s memoir – Intrigue and Lies from an Uncommon Childhood – cuts to the heart of the matter. If every family has its myths and secrets, those of the Plunkett family are particularly absorbing.

In 1974, at the age of thirteen, Plunkett travelled with her parents, older brother, and younger sister to Guyana. Then eight years into its independence from Britain, Guyana was a poor and violent society, divided along racial lines, and careening towards communism. Patrick Plunkett, Shelagh’s father, was a civil engineer ostensibly there to study the country’s hydroelectric potential. Shelagh, whose world until then encompassed suburban Vancouver where “the most exciting concern was what we were having for dinner,” was plunged into a sensuous, tropical world fraught with both delight and danger. Determined at first to hate the place, she tumbled headlong in love with her exotic and precarious new home. When her family abruptly and secretively left Georgetown – her mother sewing uncut diamonds into the hem of her dress – she was bereft.

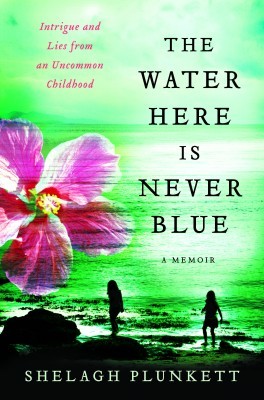

The Water Here is Never Blue

Intrigue and Lies from an Uncommon Childhood

Shelagh Plunkett

Viking Canada

$30.00

Cloth

295pp

978-0-670-06699-5

The Water Here Is Never Blue is a beautifully written hybrid: by turns coming-of-age story, travelogue, and mystery. Plunkett sheds light on the customs and cultures of two post- colonial societies in crisis, at the same time tapping into the stormy waters of adolescent angst.

A freelance writer and journalist who won the prestigious Canadian Literary Award for Personal Essay in 2007, she moved to Montreal seven years ago “because I always wanted to live here.” We spoke a couple of weeks after the publication of The Water Here Is Never Blue at Nick’s restaurant on Greene Avenue.

Elaine Kalman Naves: Was there a eureka moment when you knew you had to write this book?

Shelagh Plunkett: It started with an essay called “In a Garden,” that won the CBC Literary Award. There was a bit of a eureka moment then. I was working as an editor and freelance writer, and I got to the point where I wanted to write in a different kind of voice. And I decided I’d write about an experience I’d had as an adolescent in Guyana. I started it in what I’d call a straight-up voice, the style you’d read in a magazine like The Walrus. Then all of a sudden, these interjections of a Guyanese-sounding voice jumped into my head. I submitted it for the award and it won!

EKN: It’s an unusual voice, not just the slipping into the dialect, which is amazing, but also the voice of the “Shelagh” character – you.

SP: I wanted to write the main part of the book in the voice of a girl with the limited knowledge and understanding I had at the time. But the Prologue and Epilogue are in a different, grown-up voice that includes knowledge of the political situation that I didn’t have back then. One of the biggest challenges was to try to keep that adult combination of censorship and too much information from the main part of the book. At the same time, I hope that the voice evolves a bit. I hope that’s noticeable.

EKN: I did notice. In Timor, I think the character acts…

SP: [laughing] More troublesome!

EKN: [laughing] More out in the world. The book is a really interesting blend of the personal and the political. You show what it’s like to live in a state of adventure and excitement, but yet to not understand what’s going on. It makes the reader feel on edge, waiting for something ominous. Was that deliberate?

SP: I didn’t set out to consciously create that sort of atmosphere, but it’s what we were living with. The more I went into the past the more I remembered how it felt, and the points of discomfort I felt. I guess that infused the writing. Moments like when I was sitting with my [Indo-Guyanese] friend on the school steps, and she was telling me about her reality, how uncertain her future was going to be in Guyana, and how frightened she was. I was a fourteen- year-old muddling-along kid from the suburbs of Vancouver and I suddenly realized her life was very different from mine.

EKN: Talk about the research process for this book.

SP: At the beginning I read everything I could get my hands on about what Guyana was like and what Indonesia was like when we were there. I read lots about St. Rose’s, the [all-girls private] school I went where I learned so much. And the Internet is absolutely brilliant! I found a website where people from all over the world have posted recordings of birds. I could listen to what birds in Guyana or in Timor sound like. That really helped to immerse me. Also my father had shot thousands of slides and I watched and archived those. I was sitting in my office with the curtains drawn and watching carousel after carousel. And then my mother came to visit and she went over them with me and it triggered a lot of memories for her. I spoke a lot with her and my sister and brother. I ate Guyanese and Indonesian food. I listened to Guyanese music.

EKN: And the other part – the accessing of emotions?

SP: I don’t know how to explain accessing the emotions. Some days it worked, some days it didn’t. It was hard to predict, almost like achieving a self-hypnotic state, except that makes it sound too passive. It’s as if you have to challenge yourself. It’s a funny process.

EKN: What’s the impact of the reality of family secrets, family lies, on a growing, perceptive, and introspective child/young woman? Are those secrets and lies what led to your subsequent rebellion or was it the lack of stability in your life?

SP: [slowly] In a way. Also, my father was away a lot. I misbehaved most when Dad was away, because he and I were very close. When he was away, I put my mother through a lot.

EKN: You don’t say for sure in the book that he was spy. But I believe you pretty much think he was. Can you speculate about his motivation? You make the point in the book that, when you came back from Indonesia, you were living in a much nicer home than when you had left. And you also say that he held very conservative political views.

SP: Very conservative. In the mid- 1970s, Canada was putting a lot of money – or considering doing so – into these countries. And he was an engineer doing his job. I just think they might’ve said to him, “Just keep an eye on things, take pictures, send a report.”

EKN: Who do you think “they” were?

SP: The Canadian government! These were mostly Canadian International Development Agency (cida) projects.

EKN: Would he have seen it as protecting Canadian interests?

SP: Yes. With his politics he would’ve felt that you don’t just hand out money to struggling countries because of philanthropy. He would have felt it was right to poke around. mRb

0 Comments