Buried midway through his memoir Line Breaks: A Writing Life, George Galt leaves a surreptitious note to would-be reviewers. He writes that, as the book-review editor of the Toronto-based magazine Saturday Night, he “tried to discourage reviewers for committing gratuitous violence on innocent authors.” To characterize Galt himself as an innocent author would be an injustice to his keen expertise as the wearer of manifold literary hats, as much as to his deep familiarity with Canadian literary history. But I shall, in any case, hope to commit no such gratuitous violence on Line Breaks. It is an engaging and humanistic memoir that braids together an autobiographical account of Galt’s own “writing life” with a history of the anglophone Canadian literary scene in the late twentieth century.

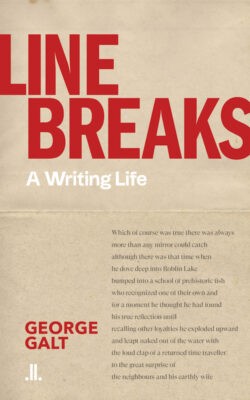

Line Breaks

A Writing Life

George Galt

Linda Leith Publishing

$24.95

paper

190pp

9781773901565

Having left Montreal, Galt navigates the feeling of being a “nobody” who has deemed his own writing to be “dreck.” The big “breaks” in Line Breaks arrive with the publication of his Greek travelogue Trailing Pythagoras, and the mentorship-turned-friendship of Al Purdy, who looms large throughout the book. In a memorable scene, Galt recounts coming to drunken blows with Purdy over the treatment of his wife, Eurithe Purdy. But the two men patch things up, and Galt hotly defends Purdy against charges of racism and misogyny in recent literary scholarship. Purdy’s is undoubtedly the most well-crafted of a subsequent revolving door of character portrayals, including those of heavyweights such as Margaret Atwood and Pierre Trudeau, who dominate the latter half of the book. Although there is certainly rich material for literary sociologists here, the speed with which Galt moves means these portraits are of more import to those with prior knowledge of Toronto’s literary scene.

Galt’s focus is on the material conditions that need to be in place to facilitate a “writing life” – the social and financial capital of navigating the who’s who of Toronto while ensuring sufficient funds through adjunct teaching or freelance writing assignments. He expends less ink on the ephemeral, the process of and motivations for writing. For example, the reader is given limited insight into the affordances of the various literary genres and forms that populate Galt’s CV: his turn to poetry later in life is only mentioned in passing in the book’s final pages. Ultimately, though, Galt succeeds in providing a from-the-trenches account of “years that were transformative for Canada’s literary culture as the old analog world began to slip into history.” The result will be of interest to all those whose lives involve writing of any kind in Canada today.mRb

0 Comments