Issa J. Boullata was nine years old when he saw a Palestinian rebel open fire on guards at the Government Printing Press across the street from his family’s house in Jerusalem. Soon, armed British soldiers began searching (and often ransacking) Palestinian homes in his neighbourhood. One day the soldiers arrived earlier than usual, and Boullata watched as his father was taken away in pyjamas with shaving foam still on his face.

In Boullata’s memoir, The Bells of Memory: A Palestinian Boyhood in Jerusalem, such details illustrate the tense atmosphere of Jerusalem during the 1930s and 1940s, a period when Palestine was under British control. Everything changed in 1948; the events of that year, called the Nakba in Arabic, are central to Boullata’s narrative. “No year is burnt into the memory of the Palestinians as deeply and as painfully as 1948,” Boullata writes.

For them, the Nakba was “the catastrophe of being dispossessed by Israel of their livelihood, their homes, and their homeland.”

Before getting to the political, however, the narrative delves into the personal, beginning with a brief family history. Boullata’s paternal grandfather was a master mason whose work included a school and a shopping complex in the Old City of Jerusalem. His maternal grandfather, a goldsmith, was the last person buried in the Orthodox Christian cemetery before it became part of the Israeli-controlled area of Jerusalem in 1948, which meant that his family could not visit the grave. A few chapters describe Boullata’s ascent through school, and the teachers who influenced him and his love of literature, at some length.

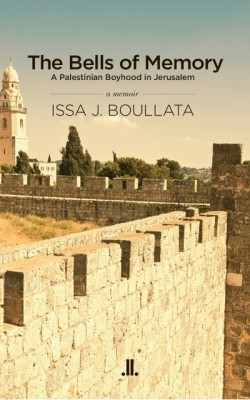

The Bells of Memory

A Palestinian Boyhood in Jerusalem

Issa J. Boullata

Linda Leith Publishing

$12.95

paper

100pp

978-1927535394

Descriptions of elaborate meals (including, for example, a “traditional lamb soup containing spicy meatballs and parsley” and “sweet semolina cookies”) tantalize the senses, and one chapter offers a fascinating portrait of the Old City of Jerusalem:

One had to go on foot through the Old City’s cobbled alleys and markets, trying to avoid laden donkeys and camels, porters carrying heavy burdens of crates of goods on their backs tightly tied by ropes to their heads, or carriers transporting dripping water-skins or large carcasses of animals from the slaughterhouse.

The Old City of Boullata’s youth is depicted as a harmonious blend of cultures, a place where “Jerusalemite Christians did not eat publicly in the presence of Muslims in consideration for their fast” and where Christians and Muslims alike enjoyed the Ramadan pastries and sweetmeats. The Jewish quarter, however, was outside Boullata’s “circle of daily life and boyhood experience.”

Written in a straightforward manner, the prose is very readable. As a whole, however, the book suffers from some structural awkwardness, shuffling around in time and sometimes repeating itself, producing somewhat uneven results. The author seems to apologize for this in the preface, stating that it “is presented to the interested reader with all the simplicity with which its parts were originally written.”

Yet, overall, the author accomplishes his stated goal of portraying what it was like to grow up in Jerusalem at that time, while he was being “unwillingly made into a person without a country.” The reader may be left hungry for details about what happened to the author and his family after the fateful events of 1948. In some ways, it feels like the first half of an autobiography, leaving ample room for a sequel. mRb

OH MY GOD….a piece of nostalgia for me as I am a Jerusalemite too, and happened to have known Issa Boullata and all his family on a very personal level: Issa was one teacher of mine at Freres College in Jerusalem( in 7th grade), besides the family considered as neighbors since living one block only from us, plus knowing his brothers quite well.

How can I buy the book? I am ready to send you a check as prepayment

Nice review thanks. I had the pleasure of meeting Issa Boullata a couple of times through my friendship with his younger brother the artist and writer Kamal Boullata. The Old City of Jerusalem that Issa writes about, which we referred to by its Arabic name Al-Quds (the Holy One) exists in our hearts and in the dreams of every Palestinian. Those who experienced living there know it for the microcosm of humanity, for its Holy Sepulchre, its Mosque of Omar, the Wailing Wall, and in our generation, for no-man’s land – a desolate barbed-wire strip that separated what was then Arab territory from the part of Palestine conquered by the Zionists in 1948, and which was and still is inaccessible to most Palestinians. Now even Palestinians living in Ramallah, a mere half hour bus ride in our time from AlQuds, cannot enter Jerusalem except with hard-to-get Israeli military permits. When a beloved Palestinian writer Henrietta Siksek ( see http://thisweekinpalestine.com/details.php?id=104&ed=21 )passed away recently, my two sisters in Ramallah applied for a permit to attend her funeral. Only one was allowed to go. Thank you Issa for reliving our Lost Paradise through your gentle memoir, balm for our exile.

This book was terrible! He says he can’t remember this or that, and then proceeds to describe it. He describes the multicultural aspect of Christian and Muslim communities, but the many Jewish migrants that settled in the area — refugees from eastern Europe, North Africa, Yemen, Syria etc — ar e all simply “Jews,” and the language of vermin is also employed in the way he describes them taking up residence in his old house, which he can apparently see from miles and miles away. A challenging situation, but I can believe a word from the arrogant, self-pitying narrator when antisemitism permeates every page. I can’t believe this was published — terribly written and, miraculously also boring!