Kim Thúy “has a thing” for ice cream. On her Italian book tour, she wanted to eat gelato. Her publicist took her to a tiny shop. “I thought there would be, you know, thirty flavours.” But no, there were only ten. “I said I wanted all ten,” she says, eyes twinkling. But there were only three scoops per cup. Okay, she said, she would have three, three, three, and one. She only made it through six – white chocolate, roasted almond, mascarpone, pistachio …

She is a marvellous storyteller, full of energy, vibrant and animated, quite unlike the jewel-like precision and restraint of her writing. The question of ice cream arises again, demonstrating the way attention to small things can exalt a life, a theme that runs gently through her new book, Mãn, recently translated into English by Sheila Fischman. She speaks of a Japanese ice-cream maker who only makes eight scoops of green-tea ice cream every year, when the tips of the tea leaves are at their tender, flavourful peak.

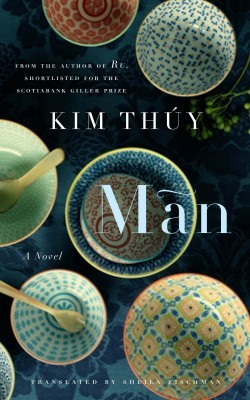

Mãn

Kim Thúy

Translated by Sheila Fischman

Random House Canada

$25.00

cloth

139pp

978-0-345-81379-4

“The next book will be about the same,” she says. “It’s my breath. I can only do that size. It’s rhythm, probably, and my rhythm is that short.” It is typical of Thúy to offer a realistic assessment of her work with both humour and humility. “I’m very loud in person, and I can never tell a short story,” she laughs. “But when I write I become very economical. Because I don’t have the vocabulary, and the knowledge of the language. I don’t feel I have the leisure of a real author who can play with the structure. So I remain quite primitive … My knowledge of French is quite restrained, so I don’t have the luxury to spread myself. I can’t fly. I fly like a chicken, only for half a second. My writing is like a chicken trying to fly.”

Of course, not every flying chicken wins the Governor General’s Literary Award on its first flapping foray. “Every word for me is a jewel, a treasure,” she says. “I worked very hard to gain that … I can sometimes understand a word very well for a long time before I know how to use it … I love those words. I have carried them.” In both books she has listed in the margins Vietnamese words linked to the text, with their French or English translations. This is intimately connected to Thúy’s experience of moving between languages and cultures. Thus the reader shares her discovery of the words.

She offers examples that demonstrate the richness to be found between languages, and the generosity of her impulse to draw the reader into her lush bicultural space. “In French when you say goodbye it’s adieu, you give someone to God. In Vietnamese when you say goodbye to somebody it’s to accompany somebody to the next starting point. So in one culture it’s the end, in the other it’s the starting point.”

She also says, “I appreciate the words for love in Vietnamese … in English and French it’s more limited.” In Vietnamese there is a word for love of a spouse, a word for love of a parent, another for love of ice cream. In French and English we have only the one verb. “If I only knew Vietnamese, I wouldn’t have appreciated this richness.”

Thúy is conscious of the distance she has traveled from her refugee childhood. She is a constitutional lawyer who also has degrees in translation and linguistics, an accomplished cook and restaurateur, wife, mother to an autistic son, and now internationally acclaimed writer. Many of the stories in her books come from her experiences or those of women in her family, but she was also a lawyer in Vietnam for three years, where she made a point of meeting ordinary people and hearing about their experiences of the war and its aftermath. She is sensitive to the many small acts that make a life, and how many of those are the daily hard work, small attentions and sacrifices of women caring for their families – even more so in time of war. “We tend to forget that without these mothers, Vietnam would have disappeared. Ordinary, everyday heroes.”

Mãn is one of those heroes, and the daughter of one. Her mother marries her to a Vietnamese man who lives in Canada. The marriage is never passionate; Mãn focuses on daily acts of care. She finds her talent for cooking in his restaurant, building a community by creating dishes that have emotional resonance for the Vietnamese immigrants who eat there, evoking the lost past of their country of birth. Then, slowly, Mãn emerges into the wider society. She meets Julie, who has an adopted Vietnamese daughter and an interest in Vietnamese culture. Julie helps Mãn open herself to friends’ love and affection, and encourages her to expand her career. Julie teaches Mãn to laugh out loud, to let go some of the restraint that allowed her to survive her childhood and marriage. The passionate love into which Mãn falls with blue-eyed Luc is a logical next step – another form of love, another enlargement of life. “Julie came in and gave her something very tangible,” Thúy says, “that Julie loved her and cared for her, that the shop would have her name, and have the plates printed with her name, and then with this Luc it becomes tangible and physical. That she could touch love.”

Julie is a composite of people Thúy says helped “carry” her. “If there is one character in this book who is close to me it is Julie. Because I am Julie now, I try to pay back by being the person who carries. I want to have the strength to carry someone. I know how to smile today, so I want to help someone who doesn’t smile.”

In Mãn, Thúy has created a gorgeous fusion not only of languages and cuisines, but of a double-cultured life. “I feel rich,” Thúy says. “You can have one culture, but when you have two you can appreciate them both, because you have a point of comparison. I’m lucky enough to have two, to know both cultures intimately.” mRb

Wonderful interview,,,