“Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in,” moaned Al Pacino’s infamous gangster Michael Corleone in the third Godfather picture. John Dunning – producer, writer, and cinematic Renaissance man – earned his rightful title as the godfather of Canadian genre filmmaking, but may also have envied Corleone the privilege of being able to leave the family business. Unwillingly roped into the celluloid trade following the untimely death of his theatre-owning father, Dunning rose through the ranks: he began as a concession hawker at age thirteen, was a theatre manager at seventeen, and co-founded Montreal’s Cinepix Inc. at thirty-five. Along the way, he caught the film bug and put Canadian genre cinema on the map, introducing the world to influential filmmakers (David Cronenberg) and memorable exploitation trash (My Bloody Valentine and Ilsa: She Wolf of the SS).

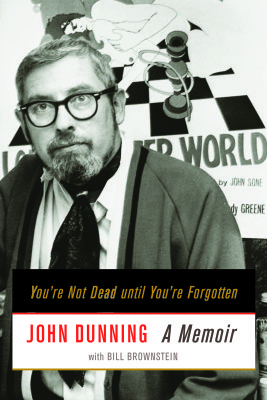

His memoir, You’re Not Dead until You’re Forgotten, paints a portrait of a man who would have preferred to remain out of the public eye. Born in 1927 in Montreal’s Verdun suburb (“the Brooklyn of Montreal,” to hear him tell it), Dunning had a life marked by poor health, frequent automobile accidents, and a crippling stage fright that plagued him until his death in 2011. The memoir, unfinished at the time of his passing, has been collected by Bill Brownstein and bookended with testimonials from Brownstein and a coterie of industry names who owe at least part of their fame to Dunning, one-half of a pair dubbed “the Roger Cormans of Canada.”

You’re Not Dead Until You’re Forgotten

A Memoir

John Dunning with Bill Brownstein

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$29.95

cloth

244pp

9780773544024

Despite those achievements, it was always the sleaze that best defined Cinepix and Dunning.

Never finding much success with anything that wasn’t outré, Dunning’s cultivation of grotesqueries and “maple-sugar porn” gave Canadian film a bad name in the eyes of some, but to others this was better than no name at all. The recollections in You’re Not Dead until You’re Forgotten are rapid- fire – scarcely is any anecdote or film allotted more than a page – yet Dunning’s passionate belief in each Cinepix picture shines through. Quietly prolific, he rarely shares a harsh word about anyone in the industry (at least not those he is willing to name), but when it comes to the censors and institutions that meddled with his provocative programming, he’s more candid.

Indeed, a cleaned-up Cinepix would have seen Dunning’s career end with a tragic quietude unbecoming of his macabre, grindhouse roots. Cinepix’s combative dealings with American studios ceased only upon its acquisition by Lionsgate in 1998. Dunning evolved his father’s business with the times, but in the new millennium the world outpaced him. His memoirs mirror the industry’s dispiritingly bureaucratic progression: exciting quick ‘n’ dirty shoots and small-time boundary-pushing gave way to the boardroom meetings and corporate head-butting of the big leagues. The closing testimonials lavish more praise on Dunning than he would likely have appreciated, but that’s because, like the screen idols he was raised on, Dunning was the rare white hat in a field of grey. mRb

0 Comments