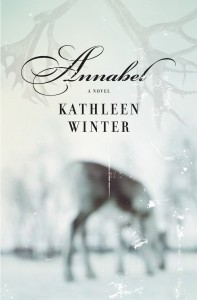

Annabel

Kathleen Winter

House of Anansi Press

$32.95

hardcover

472pp

9780887842368

Winter’s novel could not be more different from her first book of fiction, BoYs, a collection of 24 vignettes about small-town life on Canada’s East Coast. (Winter spent much

of her life in Newfoundland, though she now lives in Montreal.) Written in a minimalist style with close attention to detail if not to plot, BoYs won the Metcalfe-Rooke Award and the Winterset Award. Annabel, on the other hand, weighs in at 472 pages and is driven by an adrenalin-fuelled plot as Wayne Blake tries to solve the mystery of his identity.

At his birth, Wayne’s parents vow to divulge the secret of his ambiguous nature to no one but a neighbour who helped with his delivery. This interdiction applies even to Wayne who,

throughout his childhood, is fed pills of various colours and sizes, which he believes are for a blood disorder. In fact, they are male hormones, allowing the boy in him to dominate. His father, a traditional Labrador trapper named Treadway, tries to protect Wayne by insisting on strict conformity to the male stereotype.

Only Wayne can’t do it. From the start, he is different. His best friend in primary school is a girl. At eight years old, his preferred sport is synchronized swimming, in which he cannot participate. He spends hours watching Elizaveta Kirilovna, soloist for the Russian Olympic team, on television and dreams of purchasing an orange swimsuit and gold bathing cap, just like hers.

This story of a child struggling to understand himself, when important truths are being withheld, is powerful and moving. Winter depicts Wayne’s confusion with skill, and draws with equal dexterity a portrait of parents who, though they wound him in terrible ways, nonetheless try to love and protect him.

Winter’s descriptions of Labrador, referred to as “the big land” by locals and dominated by a hyper-masculine hunting culture, are fascinating. The city of St. John’s, Newfoundland, where Wayne’s mother grew up, and where Wayne establishes himself after high school, is vividly portrayed: the Majestic Cinema on Henry Street has “gold-painted pillars swirling with plaster curls, leaves, and Roman faces” and the houses and fish sheds of a district by the wharfs called the Battery stand on “half-rotted stilts awash with weeds.”

Offsetting these strengths are occasional lapses into sentimentality and a narrative voice that at times seems too simple to support such complex adult content. There are a few heavy-handed images, like the bridge (between the sexes?) that Wayne builds in his back yard one summer, only to see his father destroy it; or the Battery in the following passage: “The night on the Battery was a necklace of floating light, a world of dreams, part city and part ocean, a hybrid, like Wayne himself, between the ordinary world and that place in the margins where the mysterious and undefined breathes and lives.”

But these are minor objections. Winter has written an ambitious first novel set in a little-known corner of the country and peopled by memorable guides. mRb

0 Comments