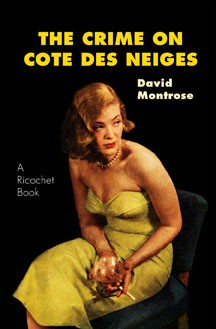

The Crime On Cote Des Neiges

David Montrose

Véhicule Press

$12

paper

160pp

978-1-55065-284-0

“His name is Charles Ross Graham,” she said. “In the early fifties he wrote three pulp-noir novels under the pseudonym David Montrose.”

“Never heard of either of him,” I said, wishing she wouldn’t do that thing with her eyes.

“Few people have,” she replied.

She handed me a spiral-bound stack of 8.5″ x 11″ paper. On the cover was a sultry blonde in a strapless gown and pearls, cigarette in one hand and brandy snifter in the other, very fifties-pulp.

“These are the galleys of The Crime on Cote des Neiges,” she said, “featuring Montreal private investigator Russell Teed. It was originally published in 1951 and is being reprinted by Véhicule Press as the first in their Ricochet Book series. Brian Busby wrote the Foreword.”

“And who’s he when he’s at home?” I asked.

“He’s a writer and literary historian,” she said. “He wrote Character Parts: Who’s Really Who in CanLit. If anyone knows anything about Graham, it’s him.”

“What do you need me for, then?” I asked, smelling fish.

“We’d like to know more,” she said, fanning me with her eyelashes.

“Okay,” I said, not wanting to seem too easy.

I took myself back up the hill to my office, put my feet up on my desk – it was too early in the day for Scotch – and got to work.

To learn my trade, I’d read Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, and Mickey Spillane, so I knew what to expect from The Crime on Cote des Neiges in terms of character, plot, and style. But how good could it be? After all, who’d ever heard of David Montrose? If he was any good, why wasn’t he as famous as his contemporaries?

When I finished the book, the answer seemed obvious: Graham simply hadn’t written enough. Being in the business, I consider myself something of an expert on private eyes and figure that if Graham had continued writing (and had had better editing), David Montrose might have become as well-known as Chandler and Spillane, and Russell Teed might still be duking it out with Philip Marlowe and Mike Hammer.

In some ways, Teed is more likeable than his American counterparts. He isn’t quite as tough as Philip Marlowe, nor as quick with his fists or gun as Mike Hammer. But he’s as cynical and hard-drinking and drives his Riley roadster through the streets of Montreal with a casual disregard of the speed limits.

No mean streets for Russell Teed, though. He grew up in Westmount. He’s university-educated. He dabbles in interior decoration: “It was the nicest living room I could put together and I liked it. One wall was dark brown and the others were heavy cadmium yellow. There was a very dark green Indian rug on the floor . . . . There were the usual tables, in blond walnut; lamps with straight drum shades the colour of the rug; and a chesterfield suite of yellow-green that a woman would call chartreuse.”

He even cooks: “I snipped a few rashers of bacon fine with scissors and dumped them into the griddle. When they were hissing hot but not crisp I threw two eggs on top of them and scrambled everything together and . . . . ate it with a glass of milk and Scotch, just enough Scotch to give the milk a proper tang.”

Hmm.

Teed is hired by Mrs. Martha Scaley, the top-tier Westmount mother of Teed’s childhood playmate Inez Scaley Sark, ostensibly to find Inez’s missing husband, night-club owner, former rum-runner, and alleged bigamist John Sark. What Mrs. Scaley really wants, though, is for Teed to track down Sark’s possibly not-so-ex first wife, thus extricating Inez from what Martha is certain is a bad marriage.

It doesn’t take Teed long to find Sark. Problem is, he’s dead, shot to death in his Côte- des-Neiges apartment. Things take a twist when Teed follows a map he found in Sark’s wallet to a Laurentian cabin, where he discovers another body, which also appears to be “The Sark.” Soon Teed is tangling with temptresses, torpedoes, molls, and hopheads, not to mention Dt. Sgt. Raoul Framboise, the only French character in the book, who has zeroed in on Inez as the prime suspect in the murder of at least one of the Sarks.

Good stuff, with enough beautiful women and dead bodies to keep the pages turning. But I wasn’t being paid to enjoy myself: I was being paid to dig up something on David Montrose himself, a.k.a. Charles Ross Graham.

So, who was Charles Ross Graham? According to Busby’s Foreword, he “belongs to a select group that includes Brian Moore, newspaperman Al Palmer and transplanted Englishman Martin Brett, writers who six decades ago brought pulp-noir to Montreal.” Born in 1920 in New Brunswick, Graham got a BA in science from Dalhousie, and came to Montreal in 1941. He did postgraduate work at McGill, served with the Canadian Army Operational Research group during WWII, then earned a master’s degree in economics at Harvard, before returning to Montreal.

He may have kept body if not soul together as a university lecturer and wage slave, but unsurprisingly his three pulp-noir novels were ignored by the Montreal papers. He cranked out The Crime on Cote des Neiges (1951), Murder over Dorval (1952), and The Body on Mount Royal (1953), which Busby considers the best, then – nothing. By 1967, after burying one wife and divorcing a second, Graham had moved to Toronto where he tried to make it as a freelance writer, finally writing a fourth David Montrose book after a hiatus of fifteen years. Gambling with Fire was also set in Montreal, but the hero was a displaced Austrian aristocrat Franz Loebek. Graham died in 1968, shortly before Gambling with Fire was released in 1969, although according to the dust jacket Montrose was “living in Toronto.”

But the lady wanted more – and I hate to disappoint a lady . . .

I contacted Busby and asked him if there was anything he could add. “I’m afraid not,” he said. “Putting together the intro all but exhausted my skills as a detective.”

My detective skills were not exhausted. I got Simon Dardick of Véhicule Press on the horn, hoping he could tell me something about Montrose/Graham. “We’ve wanted to reprint his books for a long time,” he told me. “But we know almost nothing about Graham himself. We’re hoping that a relative, friend, or colleague will see the books and come forward and tell us something about him.”

I wasn’t sure the lady was willing to wait that long.

Crime Writers of Canada is a professional association of, well, crime writers in Canada. Cheryl Freedman, former Executive Director, put me in touch with David Skene-Melvin, founding member of the CWC, antiquarian book dealer, and author of Canadian Crime Fiction 1817-1996. Could he tell me anything about David Montrose? I asked.

“Nothing you didn’t get from Busby,” he replied.

He did, however, refer me to a 1992 article entitled Montreal Confidential by Professor Will Straw, Chair of McGill’s department of Art History and Communications Studies. Along with Al Palmer’s Sugar-Puss on Dorchester Street (1950) and Martin Brett’s Hot Freeze (1954), Montrose’s first two books are briefly mentioned. “I’m glad these novels are being reissued,” Professor Straw told me. “I know nothing whatsoever about Graham, though. Sorry.”

I then did what any good investigator does when all else fails: I turned to Google. I scored half a dozen links to Montrose’s books, mostly the upcoming Véhicule Press editions, as well as a second-hand original of Gambling with Fire that you can pick up for $400, but nothing about the man behind the writer.

A couple of other leads likewise led nowhere. The trail had gone cold; Montrose had faded into almost complete obscurity. It looked like I was going to disappoint the lady after all.

“Not much to show for my money,” the lady said, when I filed my report. “Perhaps you should consider a new line of work.”

“Maybe you’re right,” I said. “Maybe I’ll become a mystery writer.” mRb

Thank you for writing this note-perfect review! I saw these books for sale in Ottawa and will have to try them out.