Regardless of age, many people are still fascinated, even enthralled, by fairy tales and their characters. How else can we explain the resurgence of fairy tale adaptations – many of which are not necessarily aimed at children – in both movies (Maleficent, Into the Woods, etc.) and television (Once Upon a Time)? While most of us are probably more familiar with the fables of seventeenth-century French writer Charles Perrault and nineteenth-century German brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, we may not realize that fairy tales and otherworldly phenomena are much older than that.

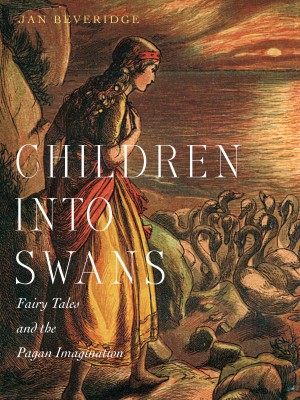

In Children into Swans: Fairy Tales and the Pagan Imagination, Jan Beveridge explores the stories, characters, settings, and themes that have preceded and often inspired the tales we know today. Mostly focusing on Irish folk tales and Norse mythology – they are “among the oldest narratives of Europe after the Classical Age … so old that their origins have long disappeared into prehistory” – Beveridge seems to particularly revel in a manuscript written around the year 1100, the Book of the Dun Cow, whose history she covers in great length and whose ancient stories she often uses to illustrate her themes.

Children Into Swans

Fairy Tales and the Pagan Imagination

Jan Beveridge

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$34.95

cloth

300pp

978-0-7735-4394-2

A companion book to Children into Swans, containing most, if not all, of the fairy tales mentioned (especially the obscure ones that can’t be found in Perrault, Grimm, or the Poetic Edda) would be an interesting idea, especially since this reviewer often googled the stories mentioned to read them in their entirety with all their lovely details, spells, and language. Furthermore, a small glossary at the end of the book for certain recurring words and peoples such as Tuatha Dé Danann (the first gods of Ireland), Fomorians (a race of demonic sea-raiders in Ireland defeated by the Tuatha Dé Danann), and Æsir (the wisest and oldest gods of Norse mythology, such as Odin and Thor) would be helpful.

The book certainly reinforces the notion that, as Audre Lorde wrote: “There are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt.” J. R. R. Tolkien dipped heavily into the old stories when creating Middle-earth (which comes from Midgard, the earth inhabited by humans in Norse mythology). Indeed, giants in Britain were sometimes called “ents,” the first dwarves in the Poetic Edda had names like Thorin and Gandalf, and there is a forest called Myrkwood in Norse mythology. What’s more, it’s hard not to think of Game of Thrones’ weirwood trees when Beveridge describes trees as having “a connection to the magical or spirit world.”

Clearly aimed at the general public as well as academics, Children into Swans is a wonderful introduction to the inner workings of Northern- European fairy tales and mythology. mRb

0 Comments