Neil Smith first discovered heaven in 1974, when his family moved to Salt Lake City. Utah was completely foreign to him: he had been a committed atheist since age six, and now, as a ten-year-old, he was surrounded by Mormons. It wasn’t the first time he’d met believers – his father’s job required the family to bounce around, and when they lived in Boston almost everyone in his class was Catholic. But faith in New England was tight-lipped: hardly something to talk about in public. Not so in Salt Lake City. At school, his classmates’ first question for him was whether he was Mormon. When he went over to their houses, he was shocked to find basements stacked with canned goods – enough to keep the family alive for at least three months in the event of apocalyptic shortages.

Yet what intrigued him most of all was their concept of heaven. Before 1978, the participation of Black people in the Church of Latter-Day Saints was restricted, and the racist policy had filtered down into the beliefs of Smith’s classmates. “Mormons believed that heaven was segregated,” he says. “They didn’t want to be with atheist Canadians or Black Africans or Japanese. Their heaven was their neighbourhood with their friends and their family.”

Boo

Neil Smith

Knopf Canada

$21.00

paper

320pp

978-0-345-80814-1

The Mormons may have been surprised at Smith’s interest in minutiae, but his readers shouldn’t be. The short story collection Bang Crunch, his first book, is packed with wacky details that prompt the reader to do a series of double takes. No character or situation is too far out: in “Extremities,” he writes both in the voice of a severed foot and from the perspective of a pair of calfskin gloves. And in “Green Fluorescent Protein,” a widow converses with her late husband’s ashes, which she keeps inside a curling stone.

The book was an international hit. It was auctioned off to the highest-bidding publishing houses around the world, “instead of being hawked around small presses in his native Canada,” as Michel Faber put it in the Guardian.

Yet, Alice Munro aside, reputations are seldom made with short stories, and nearly every review of Bang Crunch speculated about the novel that was to follow. In May – eight years and one discarded novel later – Boo will come out in both Canada and the United States. While details in the new book are as bizarre as in Bang Crunch, the setting is markedly different. Smith’s zaniest short stories take place on Earth: even the innermost thoughts and feelings of a pair of gloves are revealed against the backdrop of downtown Chicago. Now, in Boo, Smith brings his off-the-wall imagination to a whole other realm: the afterlife. And unlike his Mormon classmates, he leaves nothing out.

He tells us what kind of toothpaste they use in heaven (baking soda), and what kind of houses they live in (red-brick dormitories that look like housing projects). He tells us that there are no insects in heaven and that people get high by smoking chamomile leaves instead of dope. He shows us how heavenly buildings “fix themselves,” the shattered windowpanes inching back into being, the cracks in cement closing of their own accord. He even tells us about the kind of pineapple you get in heaven: “certainly more canned than fresh.”

In case that seems too similar to the afterlife you’d been looking forward to, don’t worry. There’s more.

Everyone in heaven is thirteen years old. And they will stay thirteen for the next fifty years – at which point they “redie,” and pass to some other realm. Our guide to this strange world is Oliver Dalrymple, nicknamed Boo because of his pale skin. He idolizes Jane Goodall and Richard Dawkins. When he is stressed out, he recites the periodic table. And he prides himself on his rationality. As he tells the “do-gooder” who welcomes him into heaven, “I’ve never had a spiritual day in my entire life.”

Smith calls himself a “science-head,” and the way that his novel echoes his own life is as minutely planned as a chemistry experiment. Boo’s last days on earth take place in the same Chicago suburb where Smith lived when he was thirteen. In fact, Boo attends Smith’s old middle school, Helen Keller Junior High. The author was not bullied the way his character is, but he wasn’t popular either: because his family never lived anywhere longer than a year or two, he hardly ever had the time to cement his childhood friendships. Boo, on the other hand, is socially inept. “He really wants friends, but he doesn’t know how to have them,” explains Smith.

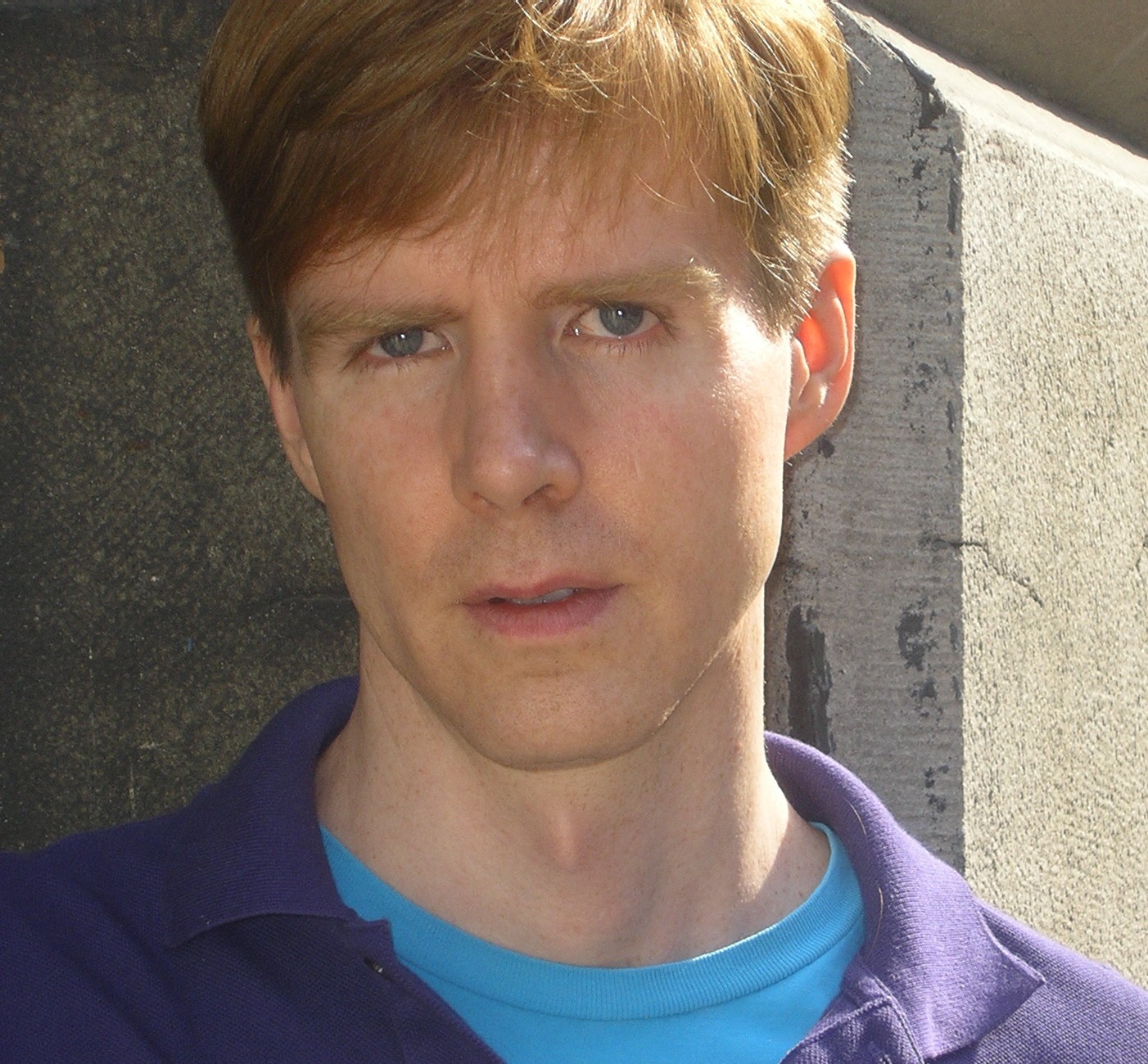

At fifty, Smith is still boyish, with a shy smile and a sheet of sandy hair he brushes out of his eyes. While working on Boo, he was also translating a Québécois novel written in the voice of a fifteen-year-old. Most people would rather forget that awkward transitional stage between thirteen and fifteen, but Smith has fond memories of it. Those are, he says, “the years when your imagination is the wildest. If you don’t have religion, you might have books. Those fictional worlds I read about were as alive to me as the Bible might be if I were religious. Every book is a Bible in its own way.”

This Bible might seem lighthearted, almost silly in its tone, which Smith admits can verge on the twee – “I have a really, really high tolerance for twee,” he says – but there is an undercurrent of deep loss. When Smith wasn’t much older than Boo, his brother died of an overdose, and it changed the way he understood the afterlife. “I’m intrigued by exoplanets, not by Jesus,” he says. “But when someone close to me dies, I can’t help imagining a parallel universe where that person lives. I know that world is fictional, but fiction brings me comfort.”

This novel is that fictional world, a kind of imperfect, secular heaven where the God-figure – Boo calls him Zig – seems to be a bumbling hippie. Smith’s late brother even makes a cameo appearance, dressed as a goth, white makeup “caked in his nostril folds.”

But the book is also an adventure story, and a fable about friendship. When Johnny Henzel, a classmate of Boo’s from Helen Keller, arrives in heaven, he fills Boo in on the gruesome details of their deaths. Boo didn’t die of a heart defect, as he originally thought. Both he and Johnny were shot by a kid at their school. And because their killer also committed suicide, Gunboy, as he is known, is among them in heaven.

Boo and Johnny’s search for Gunboy reveals the underbelly of the afterlife – the support-group-turned-militia of kids who want to avenge their violent deaths, the infirmary for thirteen-year-olds so sad and confused they want to “redie.”

Smith knows that his vision is quirky, and might not appeal to everyone. “I’m not one of those authors who want their books to live on for centuries,” he says. “I’ll be happy if it lives on for a year.” But he does hope that thirteen-year-olds will read it, that he can provide the kind of inspiration he got from writers like Paul Zindel and Shirley Jackson when he was a young adolescent.

And who knows? Maybe it will even reach the bestseller list of the Salt Lake Tribune. mRb

0 Comments