How many people once played in a band, tried their hand at writing songs, and eventually let the whole music thing fall by the wayside – but have a nagging feeling that someday they’d like to take it up again? No doubt the number is too high to count, but Montreal writer Eric Siblin decided to take up a personal music revival in earnest, and to write about the experience. Studio Grace is an intimate, at times exhaustive account of Siblin’s journey in writing and recording an album.

Writing in a straightforward, conversational style, Siblin (author of the award-winning The Cello Suites) finds himself adrift after a breakup and decides to dust off his decades-long dream of recording his own songs. He has a muse of sorts in Jo, a friend and unrequited crush who gives him sometimes brutally honest feedback on his songwriting, as well as an ally in Morey, an old friend and music business veteran with a tricked-out home studio. Later, Siblin also tries his hand at live studio recording with engineer Howard Bilerman at the storied Mile End studio Hotel2Tango, where famous records by Arcade Fire and others were laid to tape.

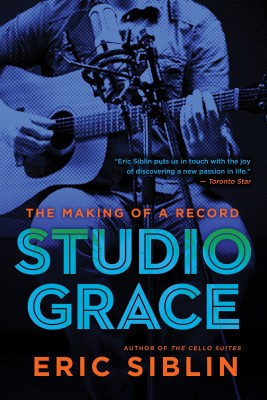

Studio Grace

The Making of a Record

Eric Siblin

House of Anansi Press

$24.95

paper

328pp

9781770899353

Like anyone entering the recording milieu this century, Siblin has to contend with radically different philosophies on the appropriate way to record. His old friend Morey is a convert to the doctrine of digital perfectionism, meticulously creating a piece with endless plug-ins and minute tweaks, while the Hotel2Tango’s Bilerman is a purist for analogue equipment and capturing the authentic moment of a live performance. As Siblin discovers, the grey area between these creative polarities is huge, and part of making music in the twenty-first century is that each artist has to figure out where they stand.

Though his musical reboot is framed as being motivated by a painful breakup, Siblin doesn’t open up much emotionally in the book. His self-portrait is of a perpetually curious, somewhat naïve fish out of water in the music community. As such, he’s a useful tabula rasa for the recording lessons he learns, though I would have found more to identify with if he’d delved a little deeper into the emotions behind the process.

One of the book’s curiosities from a Montreal perspective is the cultural split that it reveals within the city. No, not the language divide – Francophones, musical or otherwise, are barely present in the book. I’m referring to the gap between the entrenched Anglophone culture of Westmount, NDG, and the West Island, and the “hipster” artist milieu in Mile End and its environs. As a member of the latter, I found Siblin’s perspective on my community, very much an outsider’s take, to be both puzzling and strangely touching. Are we bohemian types really so strange that a fellow artist, based in the same city, who speaks the same language, still regards us as an exotic specimen? Perhaps we are.

Anyone who is already involved in recording will be intimately familiar with Siblin’s process – some might find it a refreshing reminder of the struggles we’ve all gone through, while for others it might be simply retreading old ground. A more likely ideal reader for Studio Grace is the person who’s always dreamed of recording their own songs, but never got up the nerve or the drive. For that reader, Siblin’s journey is bound to be inspirational. mRb

0 Comments