We’re not likely to get a more thorough biography of Calixa Lavallée than Anthems and Minstrel Shows, Brian Christopher Thompson’s huge and meticulous account of the life and times of the composer of “O Canada.” It’s exhaustively researched, even if sometimes the bigger picture is lost in the denseness of facts.

Composing “O Canada” was, as this book makes abundantly clear, but a moment in Lavallée’s busy musical career. He was a working musician, composing, concertizing, teaching, striving, particularly towards the end of his short and not especially easy life, to elevate the status and quality of music in North America.

Yes, North America. Lavallée spent most of his working career in the United States. He was born in 1842, in Verchères, just down-river from Montreal, and grew up in Saint-Hyacinthe (where his father led the town band). By his early teens he could play any instrument, but specialized in piano, violin, and cornet. He moved to Montreal at thirteen, and at sixteen made his debut in what was then the leading theatre in the city, the Theatre Royal on Côté Street, drawing, the press reported, “thunderous applause.”

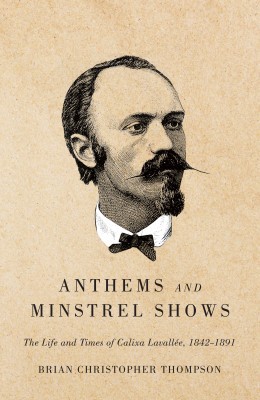

Anthems and Minstrel Shows

The Life and Times of Calixa Lavallée, 1842–1891

Brian Christopher Thompson

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$49.96

cloth

556pp

9780773545557

It’s hard to imagine today that blackface was ever so popular, but it was, and, as a highly competitive field, it drew not only huge audiences, but also the most talented performers. Still, according to Thompson, Lavallée had nobler ambitions. He spent two years in the mid-1870s studying in Paris and returned to Quebec determined to do more composing, give more concerts, and establish a state-supported conservatory of music.

Lavallée taught, he composed cantatas, Irish songs, piano études (including Le Papillon, his best-known piece during his lifetime; it’s on YouTube today),

and operas (one, The Widow, was a small- scale success). Then in 1880, he was commissioned to compose a piece – eventually “O Canada” – for the Congrès Catholique Canadien-Français in Quebec City. Thompson reveals that Lavallée’s politics were generally radical, anticlerical, and republican (in 1885, he organized a concert to benefit Louis Riel’s family), but he teamed here with a thoroughly conservative judge, A.-B. Routhier, whose text, Thompson notes, “emphasizes the primary characteristics of the French-Canadian conservative ideology of the era and of the conference: historical memory, a pastoral way of life, religious faith, patriotism, and status quo politics.”

“O Canada” had a successful premiere at the Congrès, specifically in Quebec City’s Skating Rink – in a hockey rink! – and it never looked back. It was taken to heart by French Canadians, and with Robert Stanley Weir’s we- stand-on-guard-for-thee English lyrics in 1908, by English Canadians, too.

One thing Lavallée could never get off the ground in Quebec was a state-supported conservatory of music, and Thompson suggests that this disappointment, perhaps more than anything, led him to abandon Canada in 1881 and spend his last decade in Boston where he threw himself into the promotion of homegrown American music. He was widely admired for this, but the cost was high: he died in 1891, of tuberculosis, at just forty-eight years old.

Thompson is a music scholar, formerly at McGill, now at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and we are much in his debt for so thoroughly unearthing Calixa Lavallée’s life. mRb

0 Comments