In the opening scene of Acting Class, Nick Drnaso’s new graphic novel, married couple Dennis and Rosie are trying out some role-play – they are on a first date, feigning to be strangers to one another. They make small talk about not dating for a long time, or how unbearable a previous relationship had become, but the play is brief: Dennis, whose idea it was, frets about how “organic” his performance is, while Rosie loses patience with the whole premise: “I hate that word. Organic. It’s meaningless.” The artifice, however well-intentioned, fails to transcend their dissatisfaction with the truth; they cannot get out of their own skin.

The question of what might be considered real or false, artifice or truth, is something Drnaso also explored in the Man Booker-longlisted Sabrina (2018). There, however, the contention was exteriorized: Sabrina’s brutal death sparks public debate about black sites, crisis actors, and the manipulation of the American people; private grief becomes national gossip. In Acting Class, Drnaso is more concerned with the vivid world of the interior, where truths and falsehoods tend to begin.

Acting Class Drawn & Quarterly

Nick Drnaso

$29.95

Cloth

248pp

9781770464926

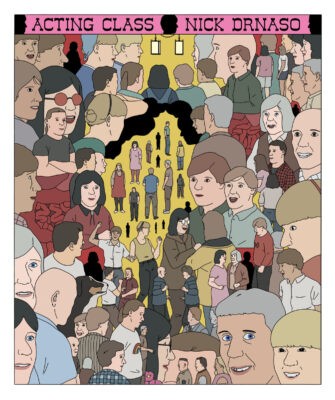

Manoeuvring so many people at once, particularly in a graphic novel, is a risk for both the writing and the imagery – so many heads in panels, so many voices to define. But Drnaso’s work is distinguished by its commitment to character and expression. The deceptive simplicity of his illustration permits for much more subtle emotion; the fact that he spends so much time lingering on these faces, and that they are made up of such basic shapes, allows for constant reinterpretation. What was previously a half-smile might later be a blank stare, and where there was once affection might now be concern.

In Sabrina, this made panels of intricate facial detail uncomfortable, almost shocking. In Acting Class, this soft matter-of-factness is still present, meaning that no scene ever feels too busy. But Drnaso’s style has shifted a little here. There is more delineation to hair and mouths, and everything has become somewhat more decided. This is most noticeable in the characters’ eyes. Where in Sabrina, eyes were simple black dots, here they are given colour. And while seemingly an effort to help distinguish each character (Rosie and Dennis look unnervingly alike), the colour instead suggests too much.

As the classes continue, and the characters come to trust the process, Drnaso transports us directly into their imagined scenes and triggered memories. The dull community college becomes variously a city at night, a bedroom, a lake house. When John assigns roles at one point, and asks Lou to be a family dog, he slips into that shape for the remainder of the role-play. Each character’s experience of the class delves deeper and deeper into personal metaphor and analogy: Rayanne, struggling with her three-year-old son, finds a green monster in his place, while Beth, who suffers from schizophrenia, plays Russian Roulette alone. Some of these lives are developed so meticulously that it is hard to disentangle what reality might be in the face of such invention and internal trembling. Others, however, seem to peter out, or hit a ceiling. Lou’s identification with his role as a dog is at first the most fascinating story of the group, but it doesn’t take long to plateau, and is eventually submerged beneath fleshier, more captivating stories.

Within a book as ambitious and beautifully told as Acting Class, though, these criticisms are practically negligible. Combined with Sabrina, and some elements of Beverly, Drnaso is capturing the palette and the pathos of everyday America, in a way that easily suggests comparison to Edward Hopper. His mastery of small talk and silence, and the vein of aggression that runs through so much of our interior lives, proves that he is deeply embedded under the skin of his characters. It means that even in a setting as artificial and as self-aware as an acting class, Drnaso’s work never reads false.mRb

0 Comments