Writers of fiction are said to stand on the shoulders of giants. In her fourth novel, Abitibi writer Jocelyne Saucier has climbed onto the shoulders of Joseph Conrad. Her setting is northern Canada rather than the Congo and her main character is a female photographer rather than the seagoing Marlow, but And the Birds Rained Down still bears a striking resemblance to Heart of Darkness.

Saucier has made a name for herself in French Canada writing novels about the North, in particular Quebec’s Abitibi region and the mining towns created when gold and other metals were discovered in the area in the late 1920s. In Les héritiers de la mine (2000), she tells the story of a Québécois prospector and his large family who lose everything when the bottom falls out of the zinc market. In Jeanne sur les routes (2006), translated as Jeanne’s Road, she describes a visit by famous labour activist Jeanne Corbin to the mining town of Rouyn in 1933. Like Conrad, Saucier is a political writer.

In And the Birds Rained Down, Saucier steps across the border into northern Ontario. She also steps out of traditional novel structure, telling her story with multiple first-person narratives. The first narrator, identified only as the Photographer, is the protagonist. We learn only one thing about her: she is on a quest through the wilderness to find a man she has never met. Sound familiar? The man’s name is Boychuck not Kurtz, and she drives a pickup not a steamboat, but these are details.

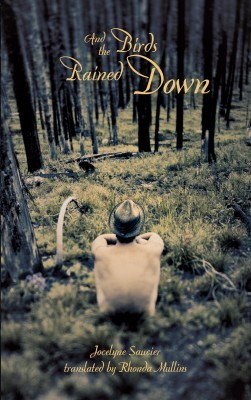

And the Birds Rained Down

Jocelyne Saucier

Translated by Rhonda Mullins

Coach House Books

$18.95

paper

155pp

978-1-55245-268-4

She never finds her man. He dies a week before she reaches his remote camp. What she finds instead is a pair of fiercely independent octogenarians, friends of Boychuck’s, eking out an existence in this unlikely northern setting. The men have freed themselves from all their past ties and responsibilities.

Their only links to civilization are two young marijuana farmers who drop by periodically with food and supplies.

This discovery astonishes the Photographer. When one of the dope growers arrives at the camp with his elderly aunt, an escapee from a psychiatric institution, things take an unbelievable turn. Like Conrad, Saucier takes a dim view of civilization. Her elderly characters have been victimized by a rapacious, consumer-oriented, institutional society, and have sought refuge in the wilderness. Unlike Conrad, though, Saucier suggests that there’s a better way forward.

She creates a Canadian utopia in which an old man can be miraculously cured of kidney failure; a woman who’s spent sixty-six years in a mental institution can discover she’s not really mad, just misunderstood; a lifelong drunk can give up scotch without a tremor; and sex can stay great to the end of one’s days. No murmurs of horror here.

Evocations of landscape are the best part of this novel, ably translated into English by Montrealer Rhonda Mullins. The historical research is strong, and Saucier plays with promising themes like aging, self-determination, and death. But her book might have shed a truer light on the human condition if it had carried a little more darkness in its heart. mRb

0 Comments