Are You Willing to Die for the Cause?, Chris Oliveros’ new graphic novel on the emergence of the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ), begins in 1963 with a Belgian immigrant. A World War II veteran and protégé of Fidel Castro who’s sick of daily Francophobia from English Canada, Georges Schoeters decides to organize. In the tiny basement apartment he shares with his wife and two children, Schoeters and his fellow FLQ founders write their manifesto. Schoeters makes his Molotov cocktails at the kitchen table and stores his boxes of stolen dynamite in the pantry. In the manifesto, they call themselves the “suicide commandos,” and after the enrolment of more revolutionaries, they plant their first bomb at the John A. Macdonald monument. Except, they don’t. Things quickly go wrong. People start to die.

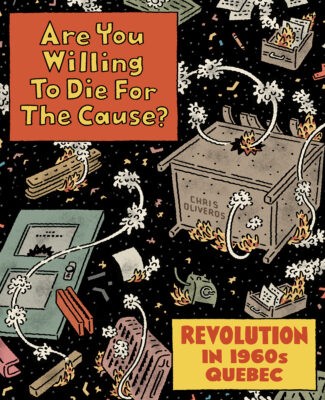

Are You Willing to Die for the Cause?

Chris Oliveros

Drawn & Quarterly

$24.95

cloth

168pp

9781770466616

Focusing on the individual men and their activities, rather than providing a widespread account of each and every FLQ attack, plot, and arrest, Are You Willing slips easily between their respective ideals and environments. While Schoeters’ story unfolds like a domestic drama – “I had taken on a [second] job to make more money,” Jeanne is quoted, “but food and rent and keeping Georges in expense money always left me flat broke” – Schirm’s in turn is more like a wartime drama, with his “guerilla army” holed up north of Montreal in the snowy forest, surviving without food or local support. Finally, with Vallières, we are deep in the territory of class violence; his management more socially involved, more charismatic, and yet still victim to the same dangerous flaws: disorganization, slipshod planning, events spiralling out of their hands.

Oliveros’ illustration of these narratives is immediately disarming. His figures and scenes are reminiscent of mid-twentieth-century comics, giving the bombings and police beatings a faux-innocent quality, as if violent, socio-political history might be the misadventures of Dennis the Menace. When guns fire they do so in clouds of “BLAM!,” and when Vallières falls to the street after a police attack, he does so with a “SPLAT.” This style easily lends itself to the slapstick comedy of chases through Montreal’s streets, or a close-up of Schoeters’ dynamite beside his kids’ cereal.

But Oliveros has done a fantastic job understanding his strengths as an artist. There is, as you might imagine, an overwhelming amount of history to cover in order to understand the FLQ and the variety of revolutionary ideals umbrellaed below those letters. And yet at no point in Are You Willing is the reader buried beneath this history. We are instead buoyed along by it, informed in every panel with a light touch. We are also led headfirst into moments of real tragedy, as with Jean Corbo, a sixteen-year-old member of Vallières’ cell, killed by the bomb he was tasked to deliver.

Are You Willing does suffer at times, however, under its baggage of history. Much of the dialogue shared between characters is historically self-aware, something that tends to work, given the comic-strip style and its lack of room for subtlety. At times though this means shoehorning in important detail – as when Schoeters says to his wife, “Remember what I told you about how when I was fourteen I fought alongside the Belgian resistance during the war?”– it can also reduce relationships to information, and people to numbers, with the francophone working class, for whom the FLQ fought, remaining faceless crowds. And given the hefty appendix detailing Oliveros’ meticulous research – as entertaining to read as the rest of the book – perhaps there was room for more small, human touches between revolutionaries; more room for difficult figures like Raymond Villeneuve, who appears here as a footnote in Schoeters’ story.

As the first of two graphic novels (the second to cover the October Crisis), Are You Willing has the potential to become a seminal text in Quebec’s assessment of its bilingual past. By writing in English, which at first seems a contentious decision, Oliveros makes available a wealth of research and history, often dismissed in the anglosphere as a local and French-Canadian issue. Looked at in this light, the book becomes a Trojan horse, one built from old-school charm and adventure, smuggling in a crucial education.mRb

Wow! Looks like something I’m interested in.