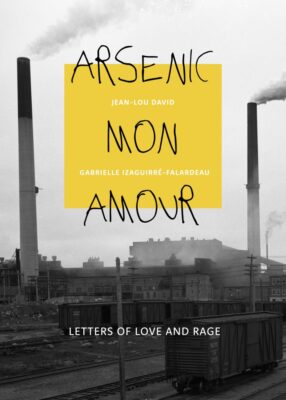

To bury into the earth and strip it of minerals is to cut holes and tunnels out of its body. What happens beneath the surface has a visible exterior effect: the leaching of the skin, the depressing pimples of industrialism. This is the image that young Québécois writers Jean-Lou David and Gabrielle Izaguirré-Falardeau paint of the mining region of Abitibi-Témiscamingue, Quebec, in their “letters of love and rage,” collected in Arsenic mon amour and translated by Mary O’Connor. Both continuously drawn to this region, the authors weave a tapestry of longing and rejection, nostalgia and despair.

Arsenic mon amour

Letters of Love and Rage

Jean-Lou David & Gabrielle Izaguirré-Falardeau

Translated by Mary O’Connor

Baraka Books

$9.95

paper

56pp

9781771863384

Another complication is unearthed in David and Izaguirré-Falardeau’s despairing love for their shared hometown: that of decaying visions of the past, “the muck and shame of broken dreams.” David’s fascination with the ghost towns scattered around Abitibi is especially evocative: ghost towns are abandoned places, buildings left to rot. They also imply spaces filled with spectres, hauntings by those who worked in the mines. These empty towns are the ruins of the good life that the gold rush guaranteed. Perhaps they are the result of the earth demanding its pound of flesh: an eye for an eye, soil stripped of its gold for the lives of its miners. What are the ephemera of a greed laced with hope?

The letters in Arsenic mon amour, clearly filled with passion and poetic talent, occasionally verge on pretension and vagueness. The title itself – a bold nod to Alan Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour (1959), a film about a love story in postwar Hiroshima, groundbreaking in its depiction of the palimpsestic present and the complex tango between personal and communal pain – is case in point. While David and Izaguirré-Falardeau illustrate, gorgeously, their personal ties to Rouyn-Noranda, their attempts at philosophizing about abstract concepts fall flat. We learn little about the protest(ors) of the past or the contours of the action that this book is supposedly calling for.

Izaguirré-Falardeau, whose father is originally from Honduras, struggles to write effectively about the impossibly complex (and ultimately exploitative) relationship between the Global North and the Global South. In an effort to combat the tragedy-porn of media coverage about Honduras, she paints the country as a place of eternal sunshine and the people as ambiguous, heroic victims of the West, an oversimplification that strips the country and its residents of agency and power. The same can be said about David’s allegorical musings on the vague “empire” that he trashes, which serves more to mystify than explain how power struggles work on a practical level.

The contemporary moment is rife with enigmatic horrors. Worldwide pandemics, climate change, the effects of globalization, and more impossibly huge issues, taken on an abstract scale, feel insurmountable. Books like Arsenic mon amour are vital in illuminating specific areas with specific issues; however, they must be careful not to fall into the same abstracting patterns that they attempt to work against. We don’t need more impenetrable anxieties or texts that slip into the passive-aggressive tone of too-late. What we need right now are specifics and plausible action points.mRb

0 Comments