C ouched in the English title of Madeleine Gagnon’s newly translated autobiography is a consciousness of the inability to accurately convey the facts of one’s life. Memoir refers not only to a Life, but more specifically to a Life in Writing: “fiction is everywhere when you tell your own story,” Gagnon writes. Autobiography emerges from the contradiction between a unified life and multiple selves.

Gagnon tells her story chronologically, starting with her happy childhood in Catholic Quebec. She then stars as an avid student and doctoral candidate in Paris, a wife and mother of two sons, a professor, a feminist activist, and, above all, a writer. Anecdotal in style, the book remains factual rather than sensational, divided into short chapters, each focusing on a specific memory.

Some chapters recount shocking misogyny during the Grande Noirceur in mid-twentieth-century Quebec. For example, during Gagnon’s studies at the Université de Montréal, one professor announced to the class that he never gave a woman more than seventy percent for an assignment, declaring “everyone knows that girls don’t go into philosophy at university to study, but to find a husband.”

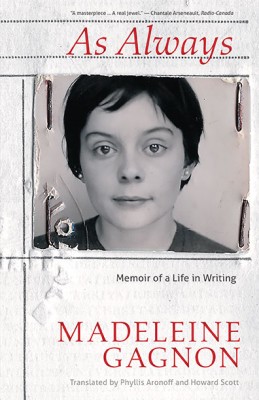

As Always

Memoir of a Life in Writing

Madeleine Gagnon

Translated by Phyllis Aronoff and Howard Scott

Talonbooks

$22.95

paper

321pp

9780889228962

Another prominent iteration of Gagnon’s persona is her “task as ambassador of Quebec literature.” Politically in favour of Quebec’s independence from Canada, her pride in local writing shines through the pages. It was during her career as an academic that Québécois, French Canadian, and francophone literature became recognized as serious subjects for study. Teaching at universities in Canada, or touring and lecturing throughout Europe, Gagnon consistently promoted Quebec writers, especially her contemporaries such as Marie Savard and Nancy Huston. She also incorporated the regional flavour of joual into her own poetry. Gagnon writes that as “an institution, literature is national: it is dependent on a nation, a people, and a geographic space. Whereas writing always transcends borders: it is universal.” The borders of nationalism are significant but limited to the edges of the page; the eyes of readers wander international terrain.

Foremost is Gagnon as a writer, poet, novelist, and critic – passages in the book illustrate her poetic perceptibility, while others employ the logical clarity of academic writing. Yet in her memoir, Gagnon’s own books and literary achievements feature as side notes. New publications are so deeply intertwined with other aspects of her life that they are inserted incidentally as contemporaneous with them. For example, one finds her writing both Poélitique and Pour les femmes et tous les autres in the summer of 1972 at a countryside cottage, but the chapter focuses on her children playing in nature while she socializes with friends, discussing Kantian transcendentalism. She recounts the devastating circumstances of her parents’ death in the same breath as her 1991 Governor General’s Literary Award.

It is exactly this marginalization of her writing that highlights its importance. Literature does not need designated segments of narration; it is omnipresent. Always generous to family, friends, and fellow writers, Gagnon is ultimately dedicated to her writing, which is her life. She writes “I walked alone. I wrote alone … I even went to a jewellery store one day to buy myself a ring to celebrate what I called my engagement to myself.”

As Always is an engaging read that invites both admirers of Gagnon’s writing and a scholarly audience. To the credit of Phyllis Aronoff and Howard Scott, Gagnon’s voice is unmistakable – intelligent, passionate, and determined – in what appears to be an effortless English translation. mRb

0 Comments