For generation after generation of devotees, jazz music remains fresh and innovative in part because of the longstanding genre tradition of re-exploring, variating, and interpolating classic pieces. Composers and musicians reinterpret jazz standards in a quest to dig deeper, drawing forth new textures where familiar pockets of rhythm and melody intersect with their creative instincts.

In the same spirit, the best jazz music archivists employ a similar approach to revisiting the genre’s history and the mythology that surrounds many of its greatest figures, especially those whose careers predated contemporary record-keeping practices.

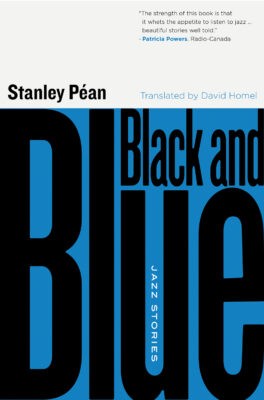

In Black And Blue: Jazz Stories, acclaimed Quebec author and host of ICI Musique’s nightly show Quand le jazz est là Stanley Péan combines his considerable knowledge of jazz history with his talent for editorial fact-finding – or debunking, as the case calls for.

Black and Blue Véhicule Press

Jazz Stories

Stanley Péan

Translated by David Homel

$21.95

paper

240pp

9781550656114

First published in 2019 in French as De préférence la nuit, Péan’s work is now available to an English-language audience, thanks to the help of Governor General’s Award-winning translator, and Péan’s fellow author and friend, David Homel.

Black and Blue emerged from an essay Péan penned unsolicited while preparing to compose liner notes for a Radio-Canada concert compilation.

“I was looking for a quote by Jean-Paul Sartre because I’m a writer and I wanted to do it properly,” Péan explains. “I thought [the quote] was in La Nausée. So I re-read La Nausée and I never found the quote I was looking for. But what I did find – because I had [last] read it when I was fifteen – was that Jean-Paul Sartre didn’t know what the fuck he was talking about!”

The work that would become the first essay in Black And Blue was born of Sartre’s hubris: Sartre had invented facts about a vocal jazz staple, “Some of These Days,” made popular in the iconic existentialist author’s era by the singer Sophie Tucker.

In La Nausée, Sartre, off the cuff, credited the song’s composition to an unnamed Jewish fellow in Brooklyn. In fact, it was the work of a man named Shelton Brooks, a Black composer from Amherstburg, Ontario.

“And it bothered me!” Péan exclaims. “I thought, ‘How can he write these things about that song, ‘Some of These Days?’

“Of course, La Nausée is a novel,” he continues. “But you can’t make up facts about a song that was not written by a Jewish guy in Brooklyn, but by a Black guy from Ontario!”

Upon finishing his reflection, Péan had the inkling to send it to Quebec literary giant Robert Lévesque, a friend and former colleague.

“I’m rarely satisfied with the things that I write,” Péan, the author of over two dozen books, confesses. “And I was tackling Sartre. And who am I to criticize Sartre? So I said to myself, ‘I’m going to send this to the harshest critic that I know, Robert Lévesque.’”

Lévesque, intrigued by the fact that his peer had not written the piece for any other reason than to write, came back to Péan enthusiastically the very same day. He requested ten more essays, proposing that they become a book in the collection he curates at Les Éditions du Boréal, Liberté grande.

Concurrently, Péan was writing a series of columns about Black life in the United States, jazz culture, and the civil rights movement for a magazine called L’Inconvenient. These would become interlude chapters in Black and Blue, which helped Péan create a bigger-picture narrative thread that lends the essay collection a sense of further cohesion.

Born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Péan immigrated to Canada with his family in 1966, when he was only eight months old. His early life in Jonquière and the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean region of Quebec was coloured both by the sounds of his mother’s music collection and her opinions on the pop culture influences the teenage Péan looked up to, which at the time included Elvis Presley, the artists of Motown, and later, Kool & The Gang and Earth, Wind & Fire.

“In my late teens, I saw Miles Davis live at the Jazz Fest,” he recalls. “I guess that was the moment that I decided, ‘This is my music.’ That was in 1985. I was nineteen years old.”

But his first interactions with the genre that would become Péan’s niche were impartial, if not indifferent.

“I was exposed to jazz very early. My mother had this huge record collection that had almost everything in it. It went from Haitian popular music and dance music to classical music, French chanson, pop and rock, and world music,” he explains. “And then you had a lot of jazz and blues. So I listened to it, not knowing that I would become obsessed.”

As recounted in a chapter that contrasts events in the life of the legendary jazz vocalist Billie Holiday to her portrayal on film, Péan and his mother’s tastes diverged along the lines of generational allegiances to taste and style.

“I saw that mediocre movie [Lady Sings the Blues] with Diana Ross when I was a kid, and I didn’t know who Billie Holiday was,” Péan says. “I was watching it because I was in love with Diana Ross. I was thirteen years old and I thought she was the most beautiful woman on the planet. And my mother said, after like twenty minutes of the movie, ‘It’s okay what she’s doing with the songs, but she’s no Billie Holiday.’

“And I’m like, ‘You cannot criticize Diana Ross!’” Péan recounts, intoning a scoffing, adolescent indignance. “My mother sent me to the record collection saying, ‘Whenever you want to listen to the real thing, go ahead and pick up a Billie Holiday record and you’ll see.’ And I did. And I didn’t like it,” he admits. “Because to me, Diana Ross was the one. I had to grow into Billie Holiday. She’s my favourite singer now. But when I was thirteen, I thought she couldn’t hold a tune.”

Péan’s obviously personal connections to the subjects in Black and Blue are the element that distinguishes his riffing on jazz lore from the myriad other chronicles that came before, providing his texts with their signature style.

Homel’s translation captures the tonal aspect of Péan’s prose with the passion that informs his perspectives. The two collaborated on the translation, often sharing lunch, music, and personal perspectives on the stories and situations Péan’s writings revisit.

“I was happy to see that Stanley Péan is serious about facts,” Homel says by email. “A lot of the time when I do translations, I fact-check and find that things are wrong. My [own] translators do the same, and [they] sometimes find mistakes,” he offers forthrightly. “I discovered the opposite here. Other online sources were wrong and [Péan] was right.”

As the reader will discern, neither personal affection nor disdain for his subjects interferes with Péan’s process. While his point of view is subjective, it is his observations, and not his judgments, that give weight to this entry into the vast literary landscape of jazz history.

Black and Blue is a distinctive, engaging read, accessible to casual fans of jazz biography, and filled with the type of minutiae that die-hard jazz enthusiasts hunger for.

“[I chose] a lot of the artists firstly because I like those artists, even though I’m not praising them all the time,” Péan explains. “I like Chet Baker’s music. But he was an asshole!

“I’m a writer and (primarily) a writer of fiction, so I like to tell stories,” the author tells me. “I happen to be telling stories about people who really existed, [whereas] in my other books, I tell stories about people I invented. You have an obligation to be as close as you can be to the truth.

“But then again, it’s a story: I’m trying to tell a story and illustrate a point.”mRb

I have come to know a lot of things from here. Thanks a lot.