In But When We Look Closer, her debut collection of eighteen short stories, Susan E. Lloy establishes a literary version of film noir, presenting us with characters whose suffering comes in many forms. In prose that fluctuates between stark and densely cinematic, Lloy explores the inner lives of the lost, the lonely, and the mentally ill. The majority of her narrators are women, but these are women as predators, as ambivalent mothers, as desperate junkies counting the minutes until their next fix.

The dark tone of the collection is set with the title story. Exhausted by their constant demands, single mother Gwendolyn sends her children out to play in a nor’easter with “hurricane-force winds and record amounts of snow.” The storm intensifies and the tension mounts as Gwendolyn spends the day drinking wine and brooding about her youthful dreams of “getting out of this place.” The vagaries of life have trapped her in Nova Scotia, where “plans evaporated like late morning fog on a warm day.” Long before she thinks to call the children back into the house, we suspect the tragedy about to unfold.

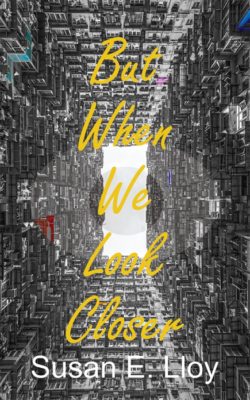

But When We Look Closer

Susan E. Lloy

NON Publishing

$19.95

paper

181pp

9781988098258

The strongest of Lloy’s stories feature complex, energetic characters who transcend easy judgment. In “Even Sad Dogs Smile,” a young painter is diagnosed with schizophrenia but believes that she must choose between her medication and her creativity, while the fate of her adopted dog hangs in the balance. The darkly playful “Escape from Reform School” explores the allure of childhood games that grow more dangerous with each passing year, and “Bad Clock” is an unapologetic paean to the pleasures and dangers of cocaine: “It was always great in the beginning hours, but then the down came. Like the great force from an ocean wave that pins you against the bottom.”

At times, Lloy’s writing loses momentum, with certain stories becoming mired in repetitive sequences of events or stilted, unrealistic dialogue. But as a whole, the collection succeeds as a haunting series of portraits of characters mourning past lovers, past selves, and the ghosts of happiness.mRb

0 Comments