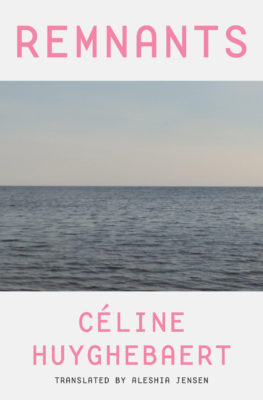

Remnants is a novel in the same way a personal diary is a novel. Céline Huyghebaert assembles bits and pieces to remember, or rather to try to discover who her dad was before his sudden death at the age of 47 from cirrhosis. Huyghebaert is a multidisciplinary artist who fuses visual art and literature, and Remnants is a beautiful example of her art. The novel works as a sort of collage, with questionnaires, photos and documents, interviews, and short stories arranged in no specific order. First published in French at Le Quartanier under the title le drap blanc, Remnants won the Governor General Award for French-language fiction in 2019. Book*hug Press published an English translation by Aleshia Jensen this June.

Remnants Book*hug Press

Céline Huyghebaert

Translated by Aleshia Jensen

$23.00

Paper

259pp

9781771667500

Jensen, who’s also translated works by Maude Veilleux, Julie Delporte, and Catherine Ocelot, does a marvellous job at translating these remnants, as it were. Dialogue, lists, dreams, and recollections: every part feels organic and has its own rhythm.

Having left her native France for Montreal in 2002, Huyghebaert missed her father’s death by a few hours only: in one interview segment, she accuses her sister Christelle of having withheld the diagnosis of their father’s illness and condition for too long before telling her to board a plane. She’s shell-shocked for the rest of her visit, and laments at how quickly her father’s apartment had to be emptied, telling her younger sister during another interview: “I felt like we were hurrying to get rid of all his things so we could forget him as soon as we could.”

She asks her sisters about how they perceive her project, and both of them have very similar answers: they see it as her way to grieve and reclaim who their father was. It feels like it’s important for her to know how her family feels about it, as if it’ll bring her some validation. She wonders if what she’s doing is right, or if she’s overstepping some boundaries by bringing up the past, especially as she prepares to undertake a second round, which is what is documented in the novel:

The first interviews were especially hard. I had this naive idea that I would be leading my family to a point of no return. But I wasn’t brave enough to break the silence. I didn’t even manage to make us relive the events; we barely pieced them back together. So I returned three years later for a second series of interviews. I wanted to talk to the same people, ask them the same questions. They would be free to correct the text as they read it, on camera.

In the end, it doesn’t feel like we’ve missed out on the accounts of those who refused. The perspective that matters most is the one we, as the reader, build alongside Huyghebaert.mRb

0 Comments