Kent Nagano, the Orchestre symphonique de Montréal’s music director since 2006, is more than just a conductor; he’s an outreach worker, constantly trying to win over new audiences to classical music, from hockey fans to street kids to Inuit communities in the Far North. He puts this mission in writing with Classical Music: Expect the Unexpected (co-written with Inge Kloepfer) – part manifesto, part impassioned plea, part sincere sales pitch for classical music as a whole. Don’t be put off by the unimaginative subtitle (“Expect the Unexpected” was the slogan for my high school yearbook in the early ’90s, and it was pretty hackneyed back then); this is a thought-provoking, entertaining, and thoroughly convincing read.

Aside from a brief chapter on Nagano’s idyllic childhood in California, where he attended a school with an exceptionally strong music program, the book is short on biographical detail, with any anecdotes serving only to back up his points about music, his life’s work. For him it’s all-encompassing – “Nothing I do has not to do with music,” he states early on – and yet the book covers a lot of thematic ground, with everything from global economics to urban planning to neuroscience worked into his passionate argument for the importance of classical music, both to society and to the human soul itself. Firmly rejecting the idea that classical is only for a greying elite, Nagano proposes that it can and should be for everyone, explaining not only why but how he’s tried to broaden its appeal.

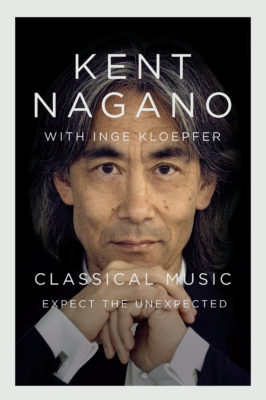

Classical Music

Expect the Unexpected

Kent Nagano and Inge Kloepfer

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$34.95

cloth

248pp

9780773556348

Despite being of the rock-adjacent baby boom generation, Nagano seems to have lived his whole life in a classical bubble, and regards other music with the bemused air of a complete outsider. His first (and seemingly only) rock concert was a Frank Zappa show in ’79, to which the potty-mouthed provocateur invited Nagano in a (successful) effort to bring the conductor’s attention to Zappa’s orchestral work.

In spite of this, Nagano takes pains not to seem like an anti-pop snob. He takes a few light-hearted potshots at easy targets (Britney Spears, Katy Perry), but stresses that he doesn’t consider classical music superior per se, just in a different realm. Essentially, his argument is simple: classical music takes more effort to appreciate, but it’s worth it. He disdains classical-pop crossovers, but had no problem with hiring Misstress Barbara to spin house music in the lobby after an OSM performance as a means to lure the ever-elusive kids into the symphony hall. (Montrealers will get a kick out of his heartfelt salutes to the city, which he calls his “lab” for trying bold new ideas.)

At times, I wondered who Nagano’s intended reader was. The book is certainly not a primer – anyone without a basic knowledge of music theory and history will struggle to keep up with his descriptions, let alone his arguments. Conversely, anyone already familiar with the classical world doesn’t need to be convinced. But if you (like me) are in the middle ground, the classical-curious if you will, you’ll come away inspired, ready to open your musical mind, and armed with some good listening tips to get started. mRb

0 Comments