Seth is a genre unto himself. The cartoonist, born Gregory Gallant, has been exploring and refining his singular vision of one corner of Canada for more than three decades. A constant over most of that time has been Clyde Fans, the saga of brothers Abe and Simon Matchcard and their doomed stewardship of the titular business they inherited from their father – yes, they’re selling oscillating fans, at a time when fans are being superseded by air conditioning. Serialized at regular intervals since first appearing in the author’s Palookaville in 1991, Clyde Fans is now finished, gathered between two hardcovers in a handsome slipcase, an objet d’art in its own right. And even for those who have been following from the start, it is a revelation.

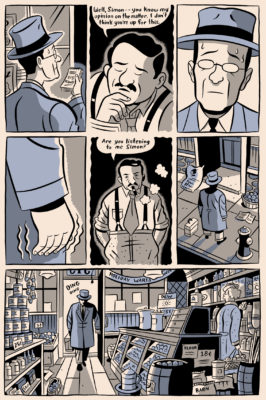

Reading Clyde Fans all in one go, it turns out, is the best way to do it. This is a story of inertia that counter-intuitively gathers a powerful momentum as it proceeds. Abe and Simon, their relationship long sundered, both obsessively picking at old emotional scabs, are emblematic of a specific type of mid-twentieth century, middle-class, white North American male: repressed, profoundly lonely, prone to an existential despair verging on nihilism. Picture Mad Men’s Don Draper, but stuck in a backwater without a trace of glamour. Dominion, their home, is Seth’s composite of various past-their-prime southern Ontario communities and older parts of Toronto. A world defined by neglect and entropy, it is also very much a post-World War Two milieu: even when the time frame extends into the 1970s, you’d barely know it, such is the brothers’ resistance to anything like true change. It all might almost be too much to bear, were it not for the sheer beauty of Seth’s images and the perfect economy of his integrated text. He wrings the maximum melancholic impact from what might look, at a glance, like a limited palette, one dominated by shades of blue, masterfully varied perspectives – and shadows, always shadows.

Seth was interviewed for the mRb by email from his home in Guelph, Ontario.

Clyde Fans

A Picture Novel

Seth

Drawn & Quarterly

$64.95

cloth

488pp

9781770463578

Seth: Not tremendously. Mostly I suspect this is due to the fact that my thinking remains remarkably consistent over time. I certainly feel like I am a different person today than I was twenty years ago, as I am sure most people do. But if I read a diary entry or an old note from ages ago I discover I haven’t changed much at all. This might be a pretty damning statement – a sign of stagnation – but I hope not. I feel like I am constantly engaging with new ideas and following new creative threads, but perhaps I have a bit of a monolithic world view. Or to put it another way, I think I was very powerfully shaped by my experiences as a child with my much older parents, and I’ve been following/examining the ideas or patterns of thinking that came from those experiences in a pretty consistent way for most of my adult life.

IM: How was it transitioning out of (and back into) Clyde Fans while taking on (and finishing) other projects?

S: Not a big problem. I’m a plodder. I plod along. I always have many, many projects on the go. I get excited about them for a week and then forget about them for a month, and then one day I come back to them, excited again. When that happens I am ready to dive in again. So a bit gets done here and there, and eventually, even if it takes twenty years, the project gets done. I sometimes feel guilty about being so scattered, but ultimately I suppose this is my desired work pattern. As I get older, the variety of the projects I am working on increases and I have come to realize how important it is to be trying different things. You learn so much from every whim you follow. If I hadn’t done Wimbledon Green (2005) as a sketchbook experiment, I would not have learned how to structure a fragmented story and then I wouldn’t have been prepared to do George Sprott (2009) for the New York Times when the opportunity arose. The tragedy of not trying something new isn’t the loss of that imagined work itself, it is the loss of several better projects down the road you will never do because you never learned the lessons that imagined project would have taught you.

IM: Your work has taught me to see certain Canadian landscapes (and cityscapes and small-townscapes and interiors) through new and more appreciative eyes. It strikes me that an essential part of your artistic mission is to find the beauty in what you call the “drab” – and that finally, the drab isn’t really drab at all. Does that strike you as an appropriate response?

S: That is a dead-on accurate insight on your part. I’m not sure when I realized it myself, but my aesthetic is extremely focused on “drabness.” And you are right, “drab” is a funny catch-all term for me. It encompasses a great deal of what might be labelled as “everyday” or “mundane” or “invisible in plain sight.” Things that many people consider dull. A lot of what I am focusing on is, of course, backward looking – much of it from the post-war era. I’m not entirely sure why I find these old buildings and streetscapes and rural scenes so beautiful, but it is not entirely nostalgia. It’s certainly not about a “golden age.” That “everything was simpler in the past” stuff is such obvious guff. That said, the lingering relics of the past in our landscape (or mindscape) have a kind of sad beauty to them – they do speak of loss and neglect. There is a strange beauty to decay that perfection cannot compete with. I have always found that a perfectly preserved building from the past – say, some Art Deco masterpiece – does not have that profound feeling of time about it in the same way as does some forgotten storefront you stumble onto while wandering about.

As a young man I was very struck by John Cage’s Indeterminacy. This spoken-word piece, ninety stories in ninety minutes, had a lasting effect on me. One of the stories is about how, in class, Cage plays a record of a very challenging Indian raga. As the tone of the music rises higher and higher, finally some student shouts out, “Turn it off! I can’t stand it any longer!” Then, after Cage turns it off, another student says, “Why did you turn it off? I was just getting into it.” This points to the idea that anything is interesting if you really take the time to study it. It’s essential to my thinking. We’ve been told that certain things are interesting and certain things are boring, but maybe that’s not true. Maybe handmaking little paper buildings is more interesting than a blockbuster action film. To be fair, you can get carried away with this idea. To paraphrase Animal Farm, “Nothing is boring, but some things are less boring than others.”

.

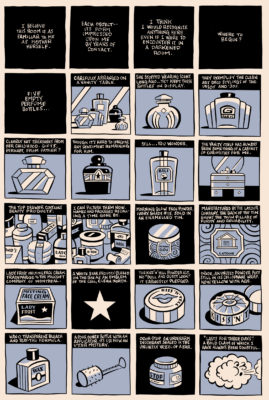

IM: One of the most striking passages in all of Clyde Fans comes on pages 282-286: the near-forensic itemization of things in the recently deceased mother’s room. Do you have a general belief in the talismanic power of the ephemeral? Are we the things we hang on to?

S: Yes, to a big degree we are. That passage stems from the fact that I grew up in a house filled with the leftover objects from an earlier time. My parents were rather old when I was born. There were siblings before me, but they were largely grown and out of the nest when I came along. Much of what was in the house were the relics of those earlier children and the relics of my parents’ earlier life, mostly post-war stuff. This clearly formed my aesthetic and much of my thinking about objects. I was fascinated by all these old gewgaws. The home I live in now is almost a symbolic recreation of that environment. It’s filled with the same kind of relics, and they have a definite totemic potency to me.

All this is a rambling way of saying that I do believe we construct ourselves, consciously and unconsciously, by the elements we graft to our personas. We do this by possessing things and by consuming things. I don’t think we are born blank slates, but I do believe we spend our lives associating ourselves with the objects and culture we consume or reject. So much of what we do is about constructing our persona. Just the other day I was thinking about how I don’t read books for pleasure – I read them to add to my sense of self. If I like a book, I am adding it to some interior treasure pile. Letting it define me. If I don’t like it, well, even the disapproval is part of some self-defining project. If you think about this too much, the idea of ego/persona gets to feel monstrous, a nightmare world of self. But if one calms down and just embraces it, it is just our way to navigate the strangeness of having an inner and an outer life. Thomas Merton, the monk, said something like – and I am mangling this quote – “To fully realize that material objects are unreal, one must first recognize just how real they are.”

IM: Is it part of your artistic impulse to make a record of a vanishing world before it’s completely gone?

S: No. I don’t think so. I’m not much of a preservationist in the true sense. I recognize, however sadly, that all things must pass. We have our time in the sun, and that’s that. I lament the loss of things and places I love, but I’m not trying to make a record for anyone else. I think what I am trying to do is impart my feeling for the vanishing world. To impart some sense of time and the potency of memory. Memory is interesting. I’ve been starting to ponder how memory might be an art form in itself. I mean, each of us is constructing a complicated work in our heads – a big, rambling assemblage crafted and edited together out of the stuff of day-to-day life. We don’t remember everything – it is extremely selective – and we don’t remember accurately. We change the memories over time to fit our makeshift narrative. It is an interesting skill. I’m fascinated by that memory world I’ve put together in my own head. It is a work in itself. Probably much more complex a work than anything I’ve ever got down on paper.

IM: Given how steeped in Canada and Canadiana so much of your work is, I’m curious as to how it “travels.” Have you found that international readers can readily relate to it? Have you had any responses from non-Canadians that have particularly surprised you?

S: Personally, I’m surprised how easily some of my most Canadian stuff has travelled. The GNB Double-C book I did a few years ago (The Great Northern Brotherhood of Canadian Cartoonists, 2011) has been translated into several languages now, and I would’ve bet money no foreign publisher would have picked that up. It’s nothing but jokes about Canadiana! Admittedly, I haven’t received a ton of feedback in general about my Canadianness. But I haven’t had any pushback, either. The American or European audiences for my work don’t seem particularly perplexed by any of the obvious Canadian elements. I’m not sure it’s an actual selling point, but it doesn’t seem to have been a stumbling block either. I admit, I’ve wondered myself if being too Canadian might be a drawback for readers, but so far…

IM: Is there a sense of liberation in having completed this enormous project and gathered it into a single volume? Conversely, is there any sense of regret? Is it like waving an old friend goodbye?

S: No sense of loss whatsoever. I am very grateful to have this millstone off my neck. Clyde Fans already feels like old work to me. I mean, I’ve been planning what book to make following Clyde for at least a decade now, and it is very nice to not have another chapter of it looming over my drawing board. In fact, I think I may be feeling a renewed interest in comics right now. Making them, I mean. In the last few years I admit to feeling some diminishing of passion for the form. I’ve been fiddling with several non-comics projects in my studio; my passion seemed to be moving elsewhere. I figured this might simply be a function of getting older, of moving on. However, that has turned around. I’ve been drawing short strips in my sketchbook lately and feeling a real joy in the work. Hopefully this joy will translate into the next book, which I am just beginning. Comics is a labourious medium. It often takes years to finish a book. Plodding along. I’m past middle age now, so I am actively wondering just how many more graphic novels I will finish before I die. That thought is not exactly a motivator. So, the joy in the doing is what counts. The feeling you get in the studio. That’s what you live for. mRb

0 Comments