Deni Y. Béchard begins with an ending in Cures For Hunger, his beautiful memoir about longing to connect with – and escape from – his mad, bad, and charismatic father. The story starts with André Béchard’s suicide at age fifty-six inside an empty house on the outskirts of Vancouver. It is winter; the power has been cut off, André’s car repossessed. A country and a coast away in Vermont, his son is too broke and broken-hearted to attend the cremation. As Béchard says, “I’d fought so long to be away from him that not even his death could bring me back.” Nonetheless, he senses that “a father’s life is a boy’s first story,” and that by unravelling the secrets of his Dad’s life, he will unearth the key to his own.

“Every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end,” said the Roman philosopher Seneca. The death of Béchard’s father catalyzes his commitment to be a writer and to tell André’s story. In fact, Béchard hammered out the first draft of what would eventually become Cures For Hunger in two weeks, just three months after his father’s suicide. “It was a story I had to write for myself,” he says. Seventeen years of rewriting followed. “I realized how the repeated telling of any story separates it from the original events and gives it a life of its own.”

Given Béchard’s nomadic nature, it is fitting that he is on the road in New York City when I catch up with him to chat by phone. Currently, the thirty- six-year-old author is on tour, promoting both Cures For Hunger and his Commonwealth Prize-winning debut novel, Vandal Love, which are being released simultaneously in the United States by Milkweed Editions, a first- rate independent, mid-sized press.

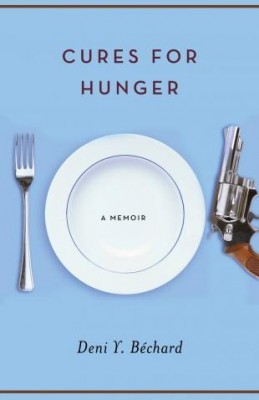

Cures for Hunger

Deni Y. Béchard

Goose Lane Editions

$29.95

cloth

322pp

978-086492-671-5

Growing up in rural British Columbia, Deni idolizes his Dad, his stories, his old “Indian” tricks, and his perilous adventures. A favourite: racing trains, where his father piles the kids into his green truck and outstrips a train, only to pull onto the crossing, as warning lights flash and bells ring. Then he turns off the ignition: Deni and his brother spot the oncoming train and scream. Just in time, Dad twists the key and lurches onto the road.

When he is with his father, Deni feels “more alive, charged … with sudden, mysterious joy.” He loves his father’s smell, pine sap and coffee, gasoline and sweat; he even loves his foul mouth and short, passionate temper. Deni is sure they are alike, though he knows little of his father’s family, life, and past.

While his Dad encourages him to fight and cuss, his mother urges him to find his true purpose. Interestingly, she makes Deni study in French, though his father, originally from Gaspésie, rarely uses his mother tongue.

Deni’s mother has her own quirks: she hates Christians and processed food with equal fervour; attends a psychic church; and believes in meditation, levitation, teleporting, and spirit guides. While all the other kids come to school with peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and cookies, Deni and his siblings get lettuce and tomato on dark crumbly bread and flat, hard cookies that look like “wet mud thrown at a wall.” His mother is also a talented artist, though sadly, she relinquishes this dream.

When Deni is in fifth grade, his parents’ acrimonious marriage falls apart. His Mom flees with all three kids to a trailer park in Virginia. Not only does Deni miss his Dad, but he also pines for the woods and streams, the mountains and valleys of his B.C. home. For the first time, he experiences hunger, subsisting on ramen noodles. Before the move, their Dad managed to keep spaghetti and meaty soups on the table through his fish stores and Christmas tree sales. Now, hunger stalks Deni “like a school bully. Hunger slept on my belly, like a hot cat. Hunger barked me into a panic like a vicious neighbor’s dog.”

As Deni probes his mother and talks to his Dad long-distance, he unearths his father’s history in jigsaw pieces. André left home as a teen, working jobs in mining and construction, so he could send money back to his poverty-stricken family. Though he never got an education, his siblings did. He loves his mother, but is bitter about his early life. Eventually, he turns to bank robbery and safe cracking, and spends time in prison. Hearing these gritty, dangerous tales only inflames his son’s imagination.

As a teen, Deni is a badass and a bookworm, aspiring to be a bank robber and a book writer. At fifteen, he flees Virginia and moves in with his father. Surfacing after bankruptcy, André now has three seafood stores and breeds German shepherds. Flea powder edges the rugs in his ramshackle house; he stashes dirty plates in the fridge, so he can reuse them without a washing.

Deni is repulsed by the slimy, smelly fishmongering business and the unromantic realities of survival – within the law. He wants to go to school, but his father hopes to hook him into fishy business. André continually tells his son that they are the same; he never needed school, why should Deni? The risk is being caught in Dad’s net: If Deni sticks around, he will end up like his father.

After André’s death, Deni contacts his father’s family who had not seen him for thirty years. He knows French: quelle action de grâce! Deni writes a letter in French to his grandmother, Yvonne, saying that he is Edwin’s son, the name his father was known by at home. A week later, he receives a call from his uncle, and sets out for Quebec, uncertain of what awaits him. His fears are quickly dispelled. His uncle resembles his Dad physically, but is gentler, kinder, a successful businessman. Deni’s grandmother is 90 and lives in her own apartment. (He tells me Yvonne is now 104 years old; he will see her and the rest of the family this summer in Rimouski). The next few days are filled with visits, all-night talks, and tears. From his father’s family, Deni learns the word agrémenter – a composite of the words meaning “to embellish,” and menteur, liar – which epitomizes his Dad, and frankly, quite a few writers. The reconnection with extended family offers joy, a bit of hope, completion.

Béchard’s memoir is alternately funny and poignant, with a meditative, leisurely pace. The narrative is at times repetitive, diffuse, and rambling, like memory. Though more colloquial and less rich in image and myth than Vandal Love, Cures For Hunger is embedded with insights. The complexities of hunger are the core of this story. Hunger is not simply a clawing emptiness in the belly: It is the yearning “for truth, for love, for a single thing that we can trust”; it is “the perfect pleasure of wanting.”

Béchard writes daily, wherever he is. When he returns to Montreal this summer, he will be “on lockdown,” in order to complete his third book, which centres on his travels in the Congo and work on grassroots conservation.

Though Béchard was the child of adversity, he managed to absorb the gifts each of his parents had to give. Thanks to his mother, he found his purpose as a writer. His Dad’s legacy was a talent for telling stories and taking chances, an almost ruthless adventurous spirit. His family’s struggles fed his commitment to human rights and activism. Ultimately for Béchard, writing is freedom and Cures For Hunger is both a journey and a coming home. mRb

This review makes me long to read the book ( and I don’t usually want to read memoirs). Thanks Amy!