In pediatric psychology, a “dandelion child” is a person who has resilience embedded deeply within them, biologically encoded into their DNA. Like the omnipresent yellow-petalled weed, they will thrive regardless of the environment they’re brought up in – even in situations that would destroy others’ spirits. In her autobiographical novel Dandelion Daughter, Québécoise author and trans woman Gabrielle Boulianne-Tremblay recounts the difficult circumstances of her upbringing – her dysfunctional childhood home, struggles with gender identity, and experiences of abuse – and the ways she pushed past these challenges to blossom into the person she is today, like a dandelion pushing relentlessly and diligently through rubble and catastrophe to reach the open air.

An actress and writer, Boulianne-Tremblay is perhaps best known for her supporting role in the 2016 independent film Those Who Make Revolution Halfway Only Dig Their Own Graves. For that part, she was nominated at the Canadian Screen Awards – the first transgender actress to receive a nomination in the whole history of the awards, a bittersweet victory of inclusion considering its more than seventy-year history. Dandelion Daughter is her debut novel, initially released in French as La fille d’elle-même and now translated into English for the first time by Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch.

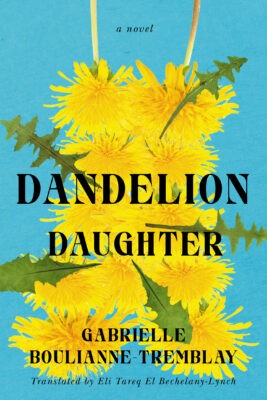

Dandelion Daughter Esplanade Books

Gabrielle Boulianne-Tremblay

Translated by Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch

$21.95

paper

280pp

9781550656183

Eventually, the protagonist leaves her semi-rural life for the anonymity and freedom that the big city provides, moving first to Quebec City and then to Montreal. In these metropolises she integrates herself into queer nightlife, finding space to experiment with her gender and blossom into the person she wishes to be. Ostensibly a transition novel, Dandelion Daughter avoids the one-dimensional cage of the form, preferring to deal in multiplicity. Rather than attempting to flatten a complex life into a single-issue narrative, Boulianne-Tremblay is interested in documenting and describing her coming-of-age experiences and the world that shaped them with ruthless honesty and dazzling detail. Transition doesn’t become a central issue until much later in the book, instead lurking quietly in the background of the narrative at first, a shadow waiting to be understood.

Where Dandelion Daughter shines brightest is in its uncanny ability to express the protagonist’s emotional realities with power and depth. Boulianne-Tremblay expertly communicates the unease and frustration of growing up in a difficult environment, with her dysfunctional family and the bullying from her peers, as well as the pain and injustice of growing up trans in a cisnormative world that seeks to stifle trans existence. Her prose succeeds at bringing the reader intimately into the feelings of the protagonist, so that we share her experiences with her; as a writer, she has a masterful grasp of fostering profound empathy through language.

Part of what enhances the emotional experience of the narrative is the style of prose. The book is written in a highly poeticized, sentimental style of prose more or less typical to the French-language memoir. Where it works, like in descriptions of emotions, it’s powerful, but sometimes it goes over the top and becomes jarring. Ways of sentimentalizing and romanticizing that may have been unremarkable in the original French occasionally become overly sappy and awkward in English, taking the reader away from the narrative.

Dandelion Daughter is a worthy addition to today’s trans literature renaissance, injecting a small-town Québécois sentiment and perspective into the increasingly popular trans memoir form. Poetic, emotional, and frequently profound, the novel showcases in gorgeous and sometimes heartbreaking detail a journey through a world that can be cruel and hostile in search of beauty, love, and acceptance.

0 Comments