Though it is almost impossible to imagine the area as anything other than a trendy, largely gentrified, and densely populated residential neighbourhood, Montreal’s Southwest borough was once the beating industrial heart of the Canadian economy. Stretched out along the Lachine Canal, from the Peel Basin and the Old Port in the east to Lac Saint-Louis in the west, the canal was the key point of connection between the Atlantic and the Great Lakes. Providing a local source of power, and integrated into railways connecting other major cities, it was a natural site for the development of major industries. Crammed into seemingly every available square inch of land that wasn’t being used for industrial and transportation purposes was the working-class housing that supported one of the largest and most densely concentrated industrial workforces in North America.

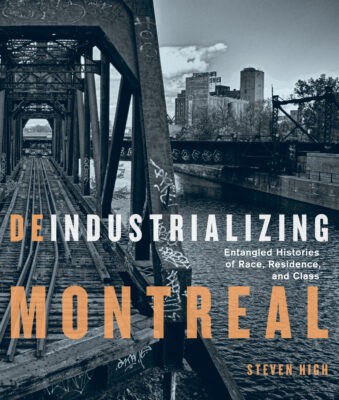

How and why this area came to be transformed from an industrial harbour to a gentrified “condoville” is the subject of Steven High’s Deindustrializing Montreal: Entangled Histories of Race, Residence, and Class. It’s the culmination of the author’s fifteen-year journey discovering his adopted neighbourhood of Point Saint-Charles and the interrelated, though socially and culturally distinct, working-class neighbourhoods that compose the Southwest borough.

Deindustrializing Montreal McGill-Queen’s University Press

Steven High

$49.95

Cloth

440 pp

9780228010753

High, a professor of History at Concordia University, focuses primarily on “the entanglements of race, residence, and class in two of these hard-hit neighbourhoods. Point Saint-Charles, a historically white working-class neighbourhood with a strong Irish and French presence, and Little Burgundy, a multiracial neighbourhood and home to the city’s English-speaking Black community.”

Though these communities share certain characteristics (and actually face one another across the Lachine Canal), the forces of depopulation and deindustrialization seem to have had opposite effects on each of the communities: where boundaries came down and solidarity emerged in the Point, solidarity remained elusive and neighbourhood boundaries were reinforced in Little Burgundy. Today, both have become highly desirable urban neighbourhoods (like much of the Southwest borough) in no small part due to their apparent historical value. It’s ironic: the historical aspect (and working-class authenticity) that drives gentrification of the area simultaneously undermines and erases the forces that have allowed these communities to last long enough to be gentrified. Longstanding institutions and lifelong residents are pushed out by those who ostensibly value their community and lifestyles.

An innovative and community-focused professor with a knack for original pedagogical activities and approaches, High, along with several other academics, tethered fourteen undergraduate and graduate courses to the communities of the Southwest borough between 2014 and 2019 (full disclosure: I took one of them, and it’s largely why I now have an MA in Public History). High mentions that this community-focused and integrated approach helped him learn through the work of his students. Students put their studies into practice conducting oral history interviews with elders and local leaders, and these in turn were developed into unique public history projects. High includes two projects developed by his students in this volume.

For an academic text, High’s writing style is accessible and – most importantly – engaging, and Deindustrializing Montreal has plenty of archival photographs and maps to help keep readers situated, even if they’re not intimately familiar with the social geography of the city. High’s expert integration of oral history into the text keeps it well grounded in lived reality, giving a history text the immediacy (if not urgency) of journalism. Gentrification, as an aftershock of deindustrialization, is as much a problem in today’s Montreal as it was forty years ago – a point underlined in this book. That we now have a history of this ongoing, largely under-appreciated, and misunderstood problem is perhaps a reminder that Montreal’s post-industrial transformation may be more an illusion and good advertising than substantive change.

Deindustrializing Montreal is a must-read for anyone seeking a better understanding of the how and the why of contemporary Montreal, and the role working-class communities played in preserving all that is now so sought after.mRb

A very interesting review of what sounds like a must-read book for anyone interested in the history of Montreal. Many thanks. I’m requesting it for my local library, and I anticipate that many will do so.