You may be looking for a bit of literary escapism to lighten the depths of winter, a “fun romp” to distract from the drag. I can say with confidence that Edem Awumey’s Descent into Night does not fit that category. However, if you seek something harrowing and suffused with poetic elegance, this may be the book for you. With a sensual realism that at times bleeds into fantasy, Awumey lays before us the life of West African playwright Ito Baraka. Shifts in tense and voice mark the separation between Ito’s existence in Hull, Quebec, and his deeply tragic past. Phyllis Aronoff and Howard Scott have done an exceptional job translating Awumey’s prose, maintaining a style that is lyrical, yet never overwrought. This is a novel of emotional complexity, of what it means to survive through trauma, and the repercussions of that survival.

Ito returns to Hull from a reading in Quebec City and scribbles feverishly in his notebook, recounting a previous life in an unnamed West African capital city. In his student days, idealistic and naive, he discovered a faith in the power of literature to incite real change in the world. While journalists were being gunned down in the streets, Ito and his friends were “dreaming with eyes open,” envisioning the shape of the country to come. Surely, a series of flyers using quotes from Beckett’s Endgame would more effectively express the absurdity of the political climate than run-of-the-mill sloganeering. And though they knew they were poking the monster with a stick, youthful hubris didn’t allow them to see their powerlessness, the riots that would devour an entire city, or the victims – Ito included – who would arbitrarily be swept up and taken away. The Ito of the present is burdened by the yoke of guilt, dying slowly of alcoholism and leukemia, “playacting at a normal life” with his equally troubled girlfriend, Kimi. And though writing his story resurrects the horned beast that fed on him and those he loved, Ito is compelled to put it onto the page as an act of both redemption and surrender.

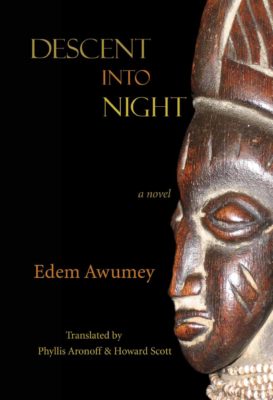

Descent Into Night

Edem Awumey

Translated by Phyllis Aronoff and Howard Scott

Mawenzi House

$20.95

paper

160pp

9781988449166

Cruelty, degradation, betrayal, regret, grief, and self-pity are just words. But Edem Awumey shows us the ways these abstractions can live and breathe in the bones, blood, and mind of a person, in time poisoning every aspect of their existence. If all of this seems a bit heavy, I can assure you that it is. But there’s an undeniable power pulsing through this novel that rewards those who can see beyond suffering and find beauty. mRb

Author photo by Julie Artacho

0 Comments