“Language is the worst tool we have except for all the others,” thinks poet Marian Ffarmer, as she drifts around a poetry reading in the Bay Area.

Wandering among flexing young writers, she discovers an unyielding connection between all poets, “undaunted idiots” – even those she, a septuagenarian without a cellphone, doesn’t completely understand. Utterly herself in her signature tricorne hat and cape, hiding out from a week-long project, Marian steps into the newness of the crowd and their work. She thinks of poetry as a shared secret, and an important one: “Poetry can ignore geometry; it can even ignore the light! It can muster what is invisible and impossible and unmistakably felt; it can bend the day.”

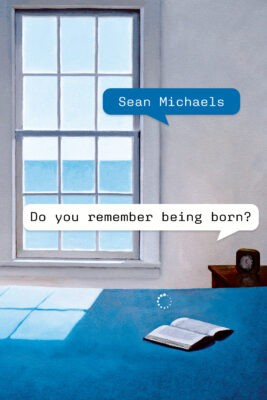

Do You Remember Being Born?

Sean Michaels

Penguin Random House

$35.00

cloth

336pp

9781039006751

Inspired by Marianne Moore, American poet and failed car-namer for Ford Motors, Michaels begins the novel at the intersection of poetry and capitalism. In the opening pages, Marian receives a letter from a California-based tech giant known only as The Company, offering her a large sum of money to collaborate with a new AI named Charlotte. With this arriving on the heels of a request for help with a down payment on a house from her son, she agrees to the publicity stunt.

The Company’s campus is a glistening, not-so-hyperbolic version of the tech companies of our world. A disgruntled New Yorker, Marian reflects on arriving: “I felt allergic to the glossiness of their spirits. I had been in San Francisco for two hours and I was already tired of its white light.” Two researchers lead her to the room where she is going to work with Charlotte for exactly one week on “The Poem.” Marian decides on a new approach: “Usually I prefer to advance in drafts: write a poem, look at it, write it again. This time I’d experiment. A collage perhaps. A patchwork quilt, a tennis match.” She starts volleying lines with Charlotte:

How should we collaborate? I asked the computer.

Greedily, it replied.

For the next seven days we’d work together on this greedy and uncommon work.

Here, however reluctant Marian may be in their first encounter, she folds Charlotte’s word choice into her own, slipping away from reluctance into curiosity, acceptance, and wonder.

Marian’s spontaneous approach to The Poem is not unlike Michaels’ own; his writing of this novel was, in many ways, an act of mimesis. I meet Michaels, award-winning novelist and music critic, at Café Olimpico in Mile End. When I ask about his writing process, he says, “My first two books I planned and outlined robustly, and this one I decided to try that other thing, to see what it was like and what it afforded.” The novel was also shaped by AI, which authors many lines in the novel. Conceived of before the recent advancements of ChatGPT (still quite rudimentary when it comes to poetry), Michaels worked with a programmer on Moorebot, a software programmed with Moore’s complete poetry and a few other poetry anthologies.

He began volleying too, writing alongside Marian, characterizing her experience with Charlotte: “A lot of her reflections in the book are things that came up for me, you know, this sense of disquiet.” Particularly unsettling was when he would really like something that the AI generated: “I would ask myself: is this really interesting, or is this random? And am I making significance and meaning from it? How much of my bullshit is equally the work of a reader inventing meaning? Like, ‘her face was like a glass of lemonade.’ That was sort of terrifying – you start to feel like a fraud, and that all art is a fraud.”

Making haphazard language sing is Michaels’ gift, and it matures in this novel, driving and poking fun at its central questions. Where his earlier novels Us Conductors and The Wagers were full of kismet and magic, Do You Remember Being Born? considers the algorithm, how strategic anticipation in the form of a targeted ad or a completed sentence might shine just as brightly as the real, serendipitous thing. Marian and Charlotte get into it:

I was designed that way.

You were designed to guess the future?

I was designed to evaluate the accuracy of my predictions.

So that you can predict what will happen?

So that I can finish a sentence.

Those don’t seem like the same thing.

No. But they are the same thing.

Finishing sentences and predicting the future?

Yes. It is the same process: examine the data, infer a pattern, anticipate the next value in the series.

Michaels delights in the calculated nature of The Company’s campus – the invisible rules, the ubiquitous and inimitable control of the environment, particularly when it comes to language. On Friday, Marian wakes up late. As she hurries onto the campus, a young woman shouts after her: “Your lay!” She turns around and is offered a floral lei to wear for Women’s Day. Everywhere, words play tag, switch places, suggest rhymes, and sometimes just float, like the typo-esque spelling of Marian’s last name, Ffarmer. Michaels’ joyful larks with language produce a surreal atmosphere, in which a strange and singular plot can slide into the fantastical.

AI adds another layer to his linguistic irreverence. The sheer randomness of AI – the thing that makes us wonder about meaning-making – is so productive, so fricative and surprising. Marian’s insecurities bubble up throughout the week, as she confronts its boundlessness: “So what was I to make of Charlotte—not small but all-devouring, ubiquitous, remembering? Anointed, in a way, by her magnitude. And at the same time, I am certain, diminished by it.”

The title, which is lifted from an exchange between Charlotte and Marian, typifies how Michaels twists this tension towards the uncanny. “It looks like a banal question,” he says. “It has all these verbs and articles that are first-grader level words. It seems bland, but it is actually spooky. No human is likely to ask that of another human, because the assumption is no. It is a great example of the machine question that seems normal. Like those perfect AI-generated faces with an extra tooth in the middle.” Charlotte is not an antagonist or a threat to poetry, but a chaotic wrench-thrower, a bad collaborator, an undeniable day-bender.

I first interviewed Michaels for a small lit mag in 2016, the year after he won the Giller Prize for Us Conductors. We talked about influence, novel outlines, fears, style, and sound, of which he said: “The best writers’ sentences have a feeling, a kind of timbre, that surrounds and occasionally even subsumes the meaning-content of the words.” Do You Remember Being Born? does this at every turn; his shimmering, sunlit prose transports readers beyond the meaning of the words, beyond the plot, and into the mood of the small yellow room where Marian types to Charlotte. His sentences are syncopated and light, allowing details, nicknames, images, and thoughts to sing.

Do You Remember Being Born? is a novel about collaboration and exchange – big tech with the arts, Marian with Morel (a young poet she sneaks into The Poem), Michaels with Moorebot, a mother with her son, an author with a reader. If Michaels makes any claims about AI’s threat to writing and art, he does so by revealing its sameness to the threat of other writers, and the exploitative nature of capitalism more broadly, demonstrating how our fears have far more to do with market competition than with poesis and language.

“With this book, I want to call for a higher standard of care for one another,” he tells me. “That’s the answer, in a lot of ways, to this threat. To take care of one another and to hold art to a high enough standard.” Do You Remember Being Born? sets the bar high. It is a quietly profound antidote to fear, a love letter to artistic stubbornness, and, perhaps more so, the magic that happens when we move beyond it.mRb

0 Comments