What constitutes a person other than a collection of memories, both those acquired in one’s own lifetime and those passed down through generations? If you strip someone of his memories, do you strip him of his soul? And if memories are the very building blocks of humanity, who decides what to construct?

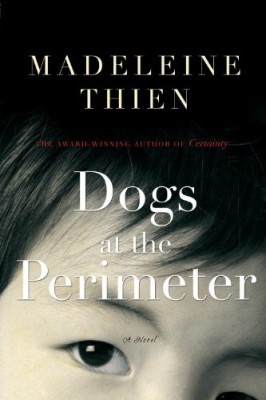

These are the kinds of questions one might ponder while reading Madeleine Thien’s second novel, Dogs at the Perimeter, a work that bravely remembers the 1970s Cambodian genocide.

Janie, the book’s principal narrator, is a Montreal neurological researcher who escaped Cambodia as a child. Yet, in 2005, the ghosts of her past still rap relentlessly on memory’s door. She recalls a discussion with her friend and colleague Hiroji about a memory theatre constructed by Camillo, a once famous sixteenth-century Italian philosopher. Apparently, when standing in this room, “one could be simultaneously in the present and within the timelines of the past.” When Hiroji suddenly disappears, Janie leaves her husband and son, and moves into her friend’s apartment, restoring a sort of “memory theatre” of her own.

Dogs At The Perimeter

Madeleine Thien

McClelland & Stewart

$29.99

hardcover

256pp

9780771084089

The Angkar (“the organization”) split apart families, forcing people to relinquish any attachment to the past, which was redefined as “memory sickness.” Those expelled from the cities were brutally brainwashed to abandon loved ones: “To pray, to grieve the missing, to long for the old life, all these were forms of betrayal.”

To survive, victims had no choice but to forge new identities and disown

their pasts. But forced amnesia invariably gave birth to a sense of shame – a recurring theme throughout the novel. Some refugees, such as Hiroji’s friend Nuong, were consequently unable to adapt to their new lives: “America’s bright smiles and proud efficiency, its endlessly flowing water, cinemas, fairgrounds, and easy optimism shamed him. He felt out of place, unknowable.”

While Thien’s portraits of human suffering are stark, and at times painfully graphic, a vague hue of beauty nonetheless clings to their edges, like a memory wishing to be expressed: “I remembered beauty. Long ago, it had not seemed necessary to note its presence, to memorize it, to set the dogs out at the perimeter,” recalls Janie.

The author’s narrative is poetic and tinged with longing, like a deep blue moan, threading its way through her characters’ lives. She tugs on this thread, bit by bit, as though unravelling the stitches of a collective wound. In quasi-dream-like fashion, she often blurs the lines that divide time, place, and character, so the reader must pay close attention, and sometimes even backpedal, to keep track of whose story is being told. Lives intersect and tangle, mimicking the interdependence of personal and collective memory.

In the end, one is reminded of memory’s holistic nature. Try to sever some of it, and chances are the disowned part will cry out louder than ever – like a phantom limb begging for reconnection. Similarly, Janie’s ghosts refuse to be silenced. Instinctively – and heart-wrenchingly – she attempts to reappropriate what her oppressors stole: “How many lives can we live?” she wonders. “How many can we steal back and piece together?” mRb

0 Comments