“Dropping bombs is the purest form of capitalism,” begins Jacob Wren’s latest book, Dry Your Tears to Perfect Your Aim. This bleak declaration underpins Wren’s polyphonic novel, a distinctly anti-war narrative that grapples with questions of violence, complicity, authority, collectivity, resistance, and doubt.

A depressed writer from a wealthy nation travels to another country, which is being bombed by missiles that are funded by the writer’s own government. The friend he stays with for the first few days advises him repeatedly to go home, telling him that he would be far more effective in stopping the bombing if he were to pressure his government from within his own country. Though he knows she is right, he doesn’t follow her advice; instead, he proceeds to walk for days into the most dangerous parts of the conflict area, until he accidentally finds himself in an autonomous zone, a “thin strip of land” that is being organized and defended by a nascent feminist revolutionary group.

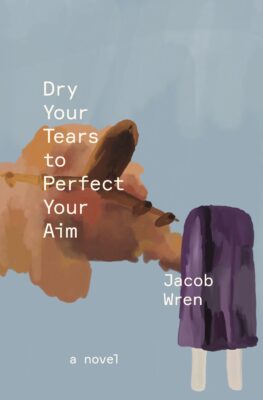

Dry Your Tears to Perfect Your Aim

Jacob Wren

Book*hug Press

$24.95

paper

220pp

9781771669047

Eventually, it turns out that he is in fact writing a book, which is the book we are reading, or a version of it. Once he returns to his home country, after being captured, imprisoned, tortured, and released by one of the military forces in the region, he sends his manuscript back to the thin strip of land, to ask for feedback from the people he has been writing about.

To summarize Dry Your Tears in this way is to simplify it considerably, and perhaps to diminish its energetic inventiveness. This is not a straightforward novel about a white saviour getting educated through travel, or even about how to make a revolution. Throughout, we get the sense that the book is being written as we read it, that its events are unfolding in real time, but also that the book is not reality, which the narrator-protagonist insists upon frequently. Wren uses an array of narrative forms – monologues, speeches, interviews, question and answer sessions, letters, and more – to counteract the supremacy of his protagonist, which is the supremacy of being both a white western subject in a world plagued by colonial violence and the narrator/author of the book in question. The result is a work written by a single author that reads in some ways like a collectively composed text.

When I speak with Wren over Zoom at the tail end of summer, he tells me that although he has been co-creating collective performances for thirty-five years (with PME-Art and other groups), he finds that process painful. Even though he is drawn to the idea of a collectively written novel, the results of his writing alone are much stronger than when he has attempted to write with others. “When I’m writing, a lot of different perspectives come up that I have to negotiate, because I contain multitudes,” he says. “And this is something that writing can do, where you can examine all the different aspects of a question alone.”

Writing from multiple voices and perspectives that often contradict or question his protagonist allows Wren to address his character’s ongoing doubts about whether he has the right to write about the inhabitants of the thin strip of land at all, as a total outsider whose government funds much of the violence they are resisting. The people of the strip are not real, but they are deeply inspired by the people of Rojava, also known as the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria or West Kurdistan. Wren has never been to Rojava; years ago, he became fascinated with the zone via an essay by David Graeber about its militant inhabitants, how they are building a revolutionary society based on feminist, anti-capitalist, and ecological practices. “It’s the same feeling I had with the Zapatistas,” he tells me, “that something is happening, it’s far away, what is my relation to it, how can I support it, what does it mean, do I know that it’s what it claims to be?”

Similarly, when he first witnessed televised “shock and awe” during the US invasion of Iraq – the tactic of bombing another region with extreme intensity, without any specific targets, to show their military power – he was initially struck by a strong desire to go there. Not because he thought he’d be of any help or that it would be the right thing to do, but “because these things are being done and you’re far away and you’re sure it’s horrifying, but you can’t actually imagine what it would be like to be in the middle of it – or you can imagine, but is what you imagine what it’s actually like?” Dry Your Tears is an artistic attempt to “go there” without actually going there, to write about the thing that perhaps should not be written about, or at least not by an outsider from a wealthy colonial nation state. Wren puts it like this: “The way that I know I’m a writer is that even when I don’t want to write about things, I can’t help but write about them.”

Though this is an anti-war novel about a region under bombardment, Wren decided not to write any death into the book – with one possible exception that I won’t spoil here. He remarks that anti-war art often makes its case by showing the violence, its brutality and senselessness, as a way to oppose it. “I don’t need to read a graphic description of someone being killed to know that I am against killing them,” he says, “and that I’m against the military-industrial complex that creates these deaths. Depicting the violence and death can be unnecessarily titillating in ways that people often don’t want to admit.”

Instead of death, there is constant dialogue and discussion, endless meetings and strategizing – this is the richness and the drudgery of the collective community emerging on the thin strip of land. The writer-narrator listens to the community’s debates about everything from permaculture to the autonomy of children to bottom-up decision-making. Anytime the narrator thinks he may understand something about this place, he is challenged by someone – not antagonistically but frankly. When he eventually sends his manuscript back to the zone, he receives several long and thoughtful letters back, engaging with and critiquing his work. One of the organizers writes that his manuscript doesn’t convey how things in the zone are “alive and full of change.” Another letter writer explains, “Even though I agreed with almost nothing you said, disagreeing with you helped me formulate my own thinking.”

When asked why inspiration won out over the worry that he didn’t have the right to write about a place like Rojava, Wren reflects that despite these questions lingering, he feels that ultimately, it’s imperative that we be inspired by groups of people anywhere in the world who are counteracting the dominant systems of capitalism, colonialism, and exploitation. And the way that he knows best to spread this revolutionary motivation is through writing. He tells me that though he has the utmost admiration for activists who oppose war, colonialism, genocide, and other horrors, he knows himself to be more of an artist than an activist: “What I can do is make art that raises questions and hopefully makes people think about things more or differently than they would otherwise. In one way, I feel this does nothing, and in another way, I hope this does something.”

Dry Your Tears is a book full of discomfort, despair, and uncertainty, as collective organizing can be; but, like collective organizing, it also brims with the energy of argument, exchange, and a staunch belief in alternative ways of living in opposition to war and subjugation.mRb

0 Comments