Everyone is dying to live: cancer patients, amateur yoginis, guests on Oprah. Inspirational posters on Facebook remind us to “focus on what’s important” and that when life gets you down to “hold your head up and keep going.” We must be the bravest, most noble, most self-directed group of people ever. We’re all “survivors” and if given half the chance we will chew your ear off with a heart-warming tale of grit and passion. Or we could get over ourselves and read Dying to Live: A Rwandan Family’s Five-Year Flight Across the Congo.

The Rwandan genocide began in April 1994, the day after President Habyarimana’s plane crashed under suspicious circumstances. Estimates now put the death toll at anywhere from five hundred thousand to one million people as he country’s two ethnic groups, the Hutus and the Tutsis, took out generations of resentment upon each other. Shortly after the first eruptions of violence, Pierre-Claver Ndacyayisenga, a schoolteacher in Kigali, his wife, and their three small children embarked on what would become a five-year walk for their lives.

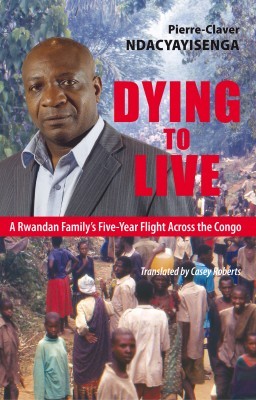

Dying to Live

A Rwandan Family’s Five-Year Flight Across the Congo

Pierre-Claver Ndacyayisenga

Translated by Casey Roberts

Baraka Books

$19.95

paper

168pp

978-1-92682-478-9

One day passes into the next, one village into the other, and there are more bullets to dodge, machetes to outrun, jungles to push through, fevers to endure, and meals to miss. Although a map is provided, it doesn’t do justice to the sense of time, space, and the unknown. The milestones of the journey are less places as they are stamps of survival: Lubutu, Ubundu, Boende, Opala, Wendji, Pokola, Yaoundé. The stakes were always impossibly high. Ndacyayisenga crafted a raft out of bamboo so his family could cross the impossibly wide Congo River; they gave up their last dollars to follow dubious guides through dense jungle; and when a fork in the road appeared they miraculously chose the way that didn’t lead to marauding soldiers.

On a cold December night in 1999, Ndacyayisenga landed in Montreal. Ten months later, after working several factory jobs and as an office cleaner, he was able to bring his family over. Though the journey was over, the struggle was not. “After escaping all the violence of our native land together, this was ultimately the battle our marriage would prove unable to survive.” And so closes the last chapter of Dying to Live.

Unfortunately, a sense of detachment undermines the book’s harrowing subject matter. Early on they lose their 11-year-old son during an exodus. This is the first real indication that they are walking in the shadow of death. When they finally find him, they only take “a few minutes to listen to the story of his adventure before (they) started out (again).” Later, they lose track of their daughter as they cross the fast moving Lubutu River. “Her disappearance introduced an element of conflict into my already exhausted group.” That’s all? She is found the next day, but the emotional relief is thin.

While the bones of the story hold up, they are often lost in the dry dust of information and the breathless recounting. A slower, gentler, and more focused approach would have worked just as well.

Finally, a note to translators the world over. Just because the French have a permissive relationship with exclamation points, it doesn’t mean you have to. mRb

0 Comments