Joan Didion said we tell ourselves stories in order to live. Elvie, Girl Under Glass is the culmination of how, with distance and healing, we can attempt to organize the chaos of our lives into coherent narratives – for art, for memory, for further healing, or maybe for activism.

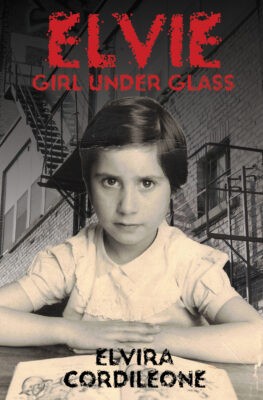

Elvie, Girl Under Glass

Elvira Cordileone

Renaissance Press

$22.99

paper

346pp

9781990086519

Cordileone was three years old when she and her mother immigrated from Campochiaro, Italy, to Montreal. From the moment she rejoins her father in Canada, Elvie is afraid of him. Her home life is chaotic, demanding, and sometimes dangerous, dominated by her father and his mental illness. As the eldest daughter of immigrant parents, Elvie bears a heavy burden: looking out for her younger siblings, attempting to protect her mother, performing household duties expected of girls, and navigating her father’s moods.

Cordileone’s father is never labelled a villain, but he is rightfully characterized as one. The memoir’s perspective is black-and-white, like a child’s. But this is never acknowledged or explored beyond Elvie’s mother, who laments her daughter’s binary thinking. Does Cordileone agree in retrospect? The years seem to have granted her some new perspective, though she still harbours anger as she details the dark and uncomfortable truths of her past.

The history of Quebec is woven into the personal narrative, albeit awkwardly. Readers from Montreal will appreciate details about the city, but Cordileone’s experience as a journalist is evident as she devotes pages to discussing events like the Quiet Revolution, Expo 67, and Bill 101. The pacing and formal, impersonal style of these passages can be jarring, and, as interesting and informative as the history is, the inclusions often feel forced. While events like the Cold War and FLQ bombings seem relevant to the author’s anxieties, she struggles to meaningfully link certain historical events to herself, one notable example being the 1969 Computer Centre Protest at Concordia University. While Cordileone was a student there at the time, she had no involvement in the events, instead witnessing it on television.

Throughout the memoir, Cordileone alludes to the future less than a handful of times. Considering the narrative ends in her twenties, this only makes the ending more unsatisfactory. She tells us she has panic attacks for the next thirty years, but we’re privy to none of that. She acknowledges her issues and her patterns, but we don’t see how she came to these realizations.

After poring over her traumatic childhood in such detail, readers might be left unsatisfied by the ending, when Cordileone leaves Montreal. Abrupt endings and unresolved plot threads can work in fiction, but this can be ineffective when dealing with real people. By ending the narrative the way she does, Cordileone deprives readers of her growth and healing, leaving them in the lurch. If we follow the dream metaphor from the prologue, then it can be assumed that the narrative ends when Cordileone leaves Montreal because for her, leaving Montreal meant freedom. If this was Cordileone’s intention, this connection could have been clarified.

Of course, a person’s life is not made up of characters and plot points, and things rarely have neat natural endings. It begs the question: How much of their life, of their soul, does a memoirist owe readers?mRb

I read “Elvie; Girl Under Glass” and found this memoir very traumatic, yet uplifting. I would love to be able to contact Elvie in order to discuss her history and years of depression. Her story has some similarities with my own immigrant from Italy hisory.

Hi, thanks for writing. We don’t have a direct contact for the author but you could try her publisher: https://pressesrenaissancepress.ca/who-weare/contact-us/