If it’s true that history is written by the winners – and history would certainly seem to bear that out – then let’s spare a thought for one of the all-time losers. The Philistine Goliath of Gath has been viewed through the ages as a sacrificial stooge for plucky little David to smite; the necessary fall guy in the ultimate underdog story. If you’re at all interested in both sides of that legendary (and legendarily brief) duel, it’s clear that Goliath never got a fair shake in the telling, whether in the Old Testament or in the many subsequent versions. But now, after a mere couple of millennia, he has, thanks to Scottish cartoonist Tom Gauld. Better late than never.

Gauld, who has experience with tweaking the perspective of a Biblical tale – having done a four-page comic of the story of Noah as seen through the eyes of his sons – here posits the concept of Goliath as a mild-mannered administrator whose only distinguishing trait, and of course his ultimate undoing, is the simple fact that he’s big. Perfectly content to be left alone pushing a pencil, he finds himself in the hour of the Philistines’ need drafted into a dubious and deceptive “patrolling” mission, but is too nice a guy to stand up for himself. Most of the book finds him keeping a melancholy watch along with his child retainer, waiting for what we know is his inevitable demise. It’s all really rather sad, with a vein of black humour inherent in the contrast between the gravity of the situation and the utter mundanity of the characters and their dialogue. In its understated way, it makes as powerful a statement about war and its waste as any more epic treatment could.

Goliath

Tom Gauld

Drawn & Quarterly

$19.95

cloth

96pp

9781770460652

In an interview conducted by email from Gauld’s home in London, I ask what drew him to this well-known story. “I had an idea to do a story about a giant,” he wrote. “Mainly because I thought it would be visually striking, and realized that maybe David and Goliath was a good story to look at, so I found a bible and looked it up. I knew pretty much straight away that it would be interesting to adapt. It’s a very one-sided story. We know almost nothing about Goliath. He’s mainly a list of measurements: how tall he is, how much his spear weighs. I wanted my story to happen in the gaps in the Bible story. The same things happen but they seem different from the other side.”

Anyone retelling a classic narrative is of course faced with the question of how to deal with the fact that the reader knows how the story ends. Did Gauld have a special strategy for that? “Not really. I just trusted that the reader, upon seeing my Goliath, would be sufficiently intrigued about what would happen to get him into the situation he’s in by the end. I hope that the reader is involved enough in my version of the narrative that the actual ending is, if not completely forgotten, at least not in the front of their mind, so when the ending does come it’s hopefully still a bit of a shock.”

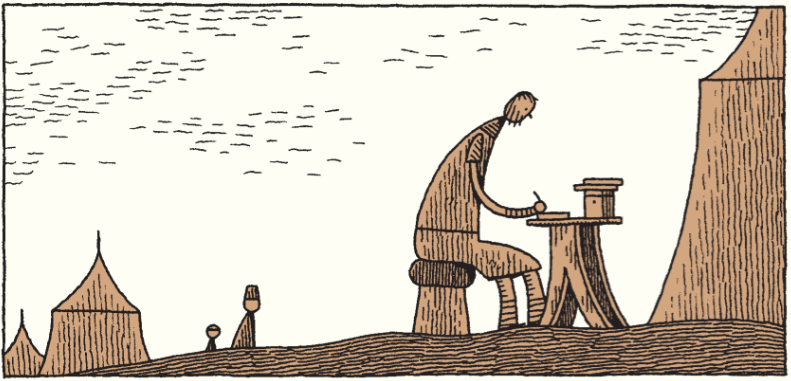

As for the book’s visual aesthetic – figures shown either in profile or straight-on, long shots but few close-ups, little depth of field – the cartoonist says it’s in keeping with his general approach. “I try and keep the artwork in my comics simple, to make it as readable as possible. I felt that taking out the perspective and keeping it to a flatter, more graphic feel would make the book feel calmer. I didn’t want the reader’s viewpoint to be whooshing all over the place, it’s all just straight on: often more like a theatre set than a movie.”

Such simplicity, the kind that serves to spotlight often-complex ideas, is something Gauld has been working toward since he was a child. Raised in Glasgow in a home that nurtured art – his architect father regularly supplied him with paper, his teacher mother encouraged his early obsession with drawing – Gauld’s earliest influences included Richard Scarry, Maurice Sendak, the Asterix and Tintin books, as well as the televised work of Oliver Postgate and Peter Firmin. “They were odd, gentle little animations which took place in surreal imagined worlds,” he says of those BBC series. “My favourite was a Viking saga called Noggin the Nog.”

Gauld’s vocation was further cultivated thanks to the enlightened approach of British higher education. “I know a few cartoonists who found their art school very anti-comics, but I never experienced that,” he says of his time at Edinburgh College of Art and the Royal College of Art (rca) in London. “My tutors were very encouraging of my comics. The art schools in Britain are quite relaxed. It was great to spend those years just playing around, figuring out what I wanted to do.”

Post-RCA Gauld teamed with fellow graduate Simone Lia to found a small publishing house, Cabanon Press (“I really like designing the book as well as creating the content, so I really enjoyed self-publishing”). Since then his work has appeared in a wide variety of forms and settings, the most prominent of which has probably been his ongoing weekly cartoon in the Guardian Review, a gig Gauld clearly relishes. “I like constraints on my work and this has lots: I’m given a theme by the newspaper, I’ve only got a day to do it, and it’s quite small. It’s like a mental exercise every Tuesday, trying to come up with something new and interesting.”

Such spontaneity stands in sharp contrast to the process that led to Goliath. It hardly seems fair for a work that can comfortably be read in a single lunch break, but two years of intensive labour went into the new book. Put bluntly, what took so long?

“Before Goliath I’d only created short narratives,” Gauld says. “So a lot of work on this book was figuring out how to tell a longer story. I began by working on vague ideas for words and pictures in my sketchbook, then I wrote out a script for the whole thing and fiddled with that quite a lot. Next I drew a rough version of the whole book, made up of quick, small, sketchy drawings, to figure out how the panels would be laid out on each page and what would be in them. Then I drew the whole book out in pencil, showed it to a few people and edited it based on their feedback. Lastly, I made the final ink drawings which you see in the book now.”

Given how touchy some Bible fans can be about adaptations, how thorough a grounding in the original did Gauld feel he needed to have? “I did a bit of reading,” he says, “as I didn’t want to make any howling errors in my story. But not that much.”

Not much, maybe. But clearly enough. mRb

0 Comments