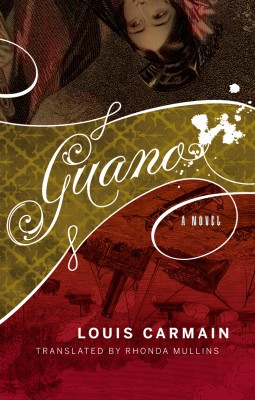

An elaborately coiffed woman, an intricate tapestry, and a woodblock sinking ship on the cover promise a story of love, history, and war. And Louis Carmain’s Guano delivers assuredly on all counts. But there’s also an off-white splotch that closer inspection reveals to be bird shit, a commodity once valuable enough to spark the minor war that provides the backdrop for this unsanitized yet sparkling historical novel with a sly contemporary feel.

Reviews of the French-language original, published in Quebec in 2013, register astonishment at the level of craft achieved in a first novel. There is a rare and impressive economy here. Carmain is trained as a historian, but he is clear on how much fact a ship can lug before it lists; he may love making every image new, but the experimental load is never too much for the prose to bear. And Rhonda Mullins’s adroit translation captures Carmain’s ready wit and wordplay beautifully, finding a faithfulness that doesn’t surrender the moxie of the English language.

We begin in Cadix in 1862, where a scientific expedition with a political side-project (or vice-versa) is preparing to set sail. Lieutenant Simón Cristiano Claro, never one to grasp the bull by the horns, is “astonished to find himself” aboard. After crossing the Atlantic and a contretemps in Chile, the Spaniards alight in Callao, Peru, where the small-time statecraft is ineffective and monotonous, but wryly funny in the accounts Simón embellishes for royal eyes.

Guano

Louis Carmain

Translated by Rhonda Mullins

Coach House Books

$19.95

paper

144pp

9781552453155

Carmain’s style is paratactic: short declarative sentences follow one upon another in rapid succession, and he trusts his readers to make their own connections. The story hums along, leavened with just enough historical insight and memorable imagery. “As everyone knows,” (I did not) “sailors do not march well.” Cannon are lined up on a ship “like decaying teeth.” In a home destroyed by war, “the loss of several joists gave the floor more spring.” The words for the long-awaited letter finally arrive, “as if in slow motion, clear and right and soft as slow tears that the eye lets fall after they have rested a time on the eyelashes.”

What makes Guano not just a fun but also a believable portrait of love and war is wealth of detail married to dearth of meaning. Life is lost painfully and most often pointlessly. Montse’s father’s horrifically casual transgression against a powerless employee, and the bloody retaliation it inspires, show the profound inhumanity of colonial society all the more powerfully because they are simply there, a brief sentence or two, uncommented on.

Unlike many historical toe-breakers, Guano keeps things short and sweet. Louis Carmain is content to say less than he knows. History, for him, “is built on trivial things that come and go, and no one notices.” It’s a convincing view, a compelling entertainment, an unexpected treasure of a novel. mRb

0 Comments