Daniel Allen Cox’s new memoir in essays, I Felt the End Before It Came, is the first memoir by a queer ex-Jehovah’s Witness put out by a major publisher. It’s a captivating, richly layered text that dismantles any reductive ideas readers may hold about indoctrination, departures, comings-out, and the practice of memoir-writing itself.

Cox wrote most of the book during lockdown in the early pandemic. The isolation of that period gave him more time, more focus, and “more insularity,” he tells me, as we chat over Zoom on a warm day in May: “I just started to write memoir like I’ve never really done in the past.”

For the duration of his writing career, which began in the mid-2000s, Cox had avoided writing directly about his experiences as a queer ex-Jehovah’s Witness, preferring to address these aspects of his life through fiction. But in the space that the early pandemic provided, he felt called to write more starkly about himself, prompted in part by the nudges of many friends over the years – nudges he had initially waved away.

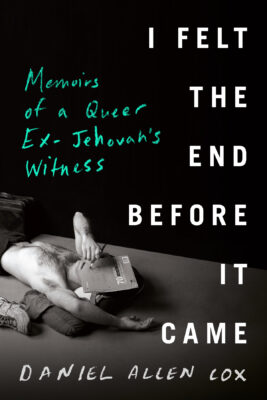

I Felt the End Before It Came Viking

Memoirs of a Queer Ex-Jehovah’s Witness

Daniel Allen Cox

$32.95

cloth

240pp

9780735242104

The memoir begins with “The Letter,” an essay which serves as an introduction to the Jehovah’s Witnesses. It’s also a complex reflection on Cox’s upbringing as a Witness in the West Island, his growing awareness of his own queerness (which is strictly forbidden by the Witness leadership), and his more or less voluntary departure from the group, called “disassociation,” at the age of eighteen.

This sounds like a fairly linear story: a childhood of indoctrination, followed by self-discovery and rebellion, followed by departure. We may expect a linear narrative when it comes to stories of exiting restrictive or coercive religious orders or cults – you’re in, and then you get out. However, this first essay complicates that notion: “none of my departures were as simple as they had first seemed,” Cox writes.

His first definitive act of departure was writing “a breakup letter” to the Witness elder who confronted him about his rumoured homosexuality – a letter that he has no copy of and can’t remember the contents of but that he considers to be “the best thing I’ve ever written.” The letter was “a feeling: a desperation, a soul leak, a horniness for a future that made sense,” and it was also “the first proof I’ve ever had that I could think for myself.”

This first, life-changing point of departure was also a point of coming out and a point of beginning. Cox’s memoir leads us through a layered series of reflections on how that departure has reverberated in his life through the subsequent decades, and how relearning and redefining words has been a crucial survival and liberatory strategy for him. “I would forever be leaving the Jehovah’s Witnesses,” he writes. To this day, he is still surprised by how the Witness-taught definitions of certain words pop up for him. For example, in the Witness sociolect, “understanding” is a process that has to come from the outside – from God or from the strict instruction of elders, rather than a process that can happen from within, through independent thought and reflection.

I Felt the End Before It Came is yet another iteration of that leaving: It finds Cox laying bare his own history, including all its gaps – in record, in memory, in language. This is Cox’s first long-form work of nonfiction – it is a departure, but also another beginning. Having previously published four novels (Shuck, Krakow Melt, Basement of Wolves, and Mouthquake), his decision to publish a memoir, especially one that addresses the traumas and manipulations of an insular religious order, will change his relationship with his readers – and likely gain him many more. “Comings-out are perpetual,” he tells me, “because, ideally, self-discovery is perpetual.”

His ongoing openness to self-discovery is palpable in these pages. The essays take us from reflections on stuttering, preaching, and finding meaning in “betweenness” to an exploration of Michael Jackson’s and Prince’s respective histories with the Witnesses; to Cox’s experiences with alcoholism and sobriety; to a brief history of his time spent living in late-’90s New York, engaging in queer porn and protest in parallel.

Cox’s approach to shaping his memoir was to show a process of questioning in its very structure. “I wanted to show unfolding awareness on the page,” he says. Many of the essays in the book pose “questions that aren’t fully resolved and actually may not be for a few essays more” – or that may even remain unresolved by the book’s end. This lack of simple resolution is one of the book’s strengths, since it demonstrates a form of understanding that emerges from considering and reconsidering one’s life, as opposed to the Witness-defined “understanding” that is static and dependent on hierarchy.

“The End of Times Square” is Cox’s essay on living in New York, which plays off Samuel R. Delany’s lauded Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. It’s one of the best in the bunch, a controlled chaos of spontaneous queer youthfulness, erotic and pornographic experimentation, queer protest, and sex work amid Giuliani’s homophobic crackdowns and widespread Y2K panic. Cox remembers feeling completely serene in the face of Y2K doom, in the middle of a huge crowd in Times Square on New Year’s Eve, 1999. “The thing about growing up in a doomsday cult is that it’s always the end of the world,” he writes. Elsewhere in the essay, he notes: “I was prepared for everything by being prepared for nothing.”

For Cox, the importance is figuring out how to separate the doomsday jargon of cultish groups from the actual realities of real-world catastrophes like climate change, global food insecurity, and the rollback of trans and queer rights. How, the book asks, can we understand both the real threats and the possibilities inherent in endings? How might we contend with disasters on earth, without the comforting belief that we will be miraculously saved when it is destroyed? “I’m immune to the trite notion of Armageddon and the end of the world,” Cox says, “because I feel that it’s been really overused in my life. But I hope that I’m not too immune to it, not so much that I don’t take action on really urgent unfolding things.”

Now that he has completed this memoir, Cox is taking a step back from mining his own experiences in his work. He’s currently focused on a collection of essays about the underground life of cities. He also, probably to the excitement of many of his longtime readers, feels compelled to return to fiction for the first time in many years. “A lot of my heart is tied to fiction,” he tells me. “Fiction is there, beating under the surface.”mRb

I was basically born into the JW’s bc my parents already were in that cult by the time i was 5 and were baptized in 1956. I was baptized in about 1963 as all my friends were too and even though at 13 you can’t decide your affliation to a religion at that age we all were doing it. So I was disfellowshipped at the age of 32 for adultery. I don’t believe in it for several reasons one of which is they handle sexual predators in-house which they are not supposed to so they quite often try to hide them. They are very family oriented which is a good thing so that is a pro point for them but going door to door was not fun and if you were baptized you were expected to do that and attend meetings 3 times a week. It is a heavy load and even worse for an elder which my father was.