A first novel without a single misstep, In a Wide Country showcases Robert Everett-Green’s unfaltering ability to fashion resonant set pieces from the raw materials of human memory – a striking image, a telling object, a colour, a snippet of dialogue, and healthy doses of hope and humiliation.

The narrator Jasper is a grown man in the first and final chapters, but in the remaining forty-nine the perspective is that of his younger self, a boy on the cusp of manhood whose fiercely independent mother drags him along for a “fancy-free” summer on the road. The credible first-person narration doesn’t just show the world through young Jasper’s eyes, but subtly drops clues as to how older Jasper achieves this heightened recall. There is the “Drawer of Shame” where mother and son consign swiped objects as mementos of their failure, and the drawings and lists young Jasper makes to pass time while shadowing his mother on modelling gigs. It’s almost like he knew he’d want to write everything down one day.

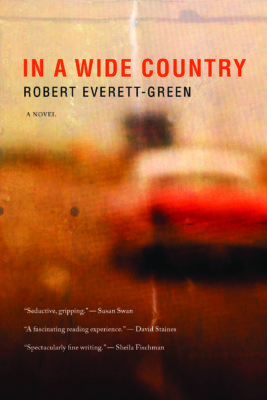

In a Wide Country

Robert Everett-Green

Cormorant Books

$22.95

paper

256pp

9781770865006

As mother and son head west, a series of short stays yields experiences that are formative but never comfortable. In one Alberta town, Jasper’s play with a distant relative turns disturbingly violent; in the next, he has a first sexual encounter, shortly before he and his mother are driven out by small-town prejudice.

In Edmonton they flirt with stability: Corrine rents an apartment and patches together work while Jasper balances his hectic family life, volatile friendships, and the bittersweet thrill of first love. Left to his own devices, he develops courage, street smarts, and an easy gift for storytelling; scrupulous honesty is a luxury he can ill afford.

Everett-Green is especially good at revealing the small-minded hate and violence just beneath the skin of the neighbourly post-war consensus. The upstanding citizens of this golden age constantly seek outsiders to persecute, a pattern dramatized repeatedly in harrowing, bloody scenes of children playing grown-up. Jasper’s childhood is difficult, unpredictable, and often disappointing, but also shot through with magic and triumphs snatched from the jaws of defeat.

The story may be interesting, but the telling is phenomenal. In sentences honed with journalistic concision and precision, Everett-Green finds poetry in calling things by their correct names: skaters career, men stride; farmland is divided into quarter-sections, floor covered in broadloom. Dialogue and period details are time-stamped in a way that feels earned, never forced, convincingly evoking a bygone era with a realism whose fit and finish recalls masters like Alice Munro and Russell Banks.

As opportunity after opportunity implodes, Corinne and Jasper head further west, until they wash up in Vancouver, a city “for people who couldn’t make up their mind what they were looking for.”

Some readers may be attentive and perceptive enough to see where this road trip will end. The rest of us will enjoy the surprise at the end of the road, and be humbled to reread and discover the many clues we missed along the way, hiding in plain sight – one more cause to marvel at the understated cogency of the storytelling that makes In a Wide Country such an affecting, enjoyable trip.mRb

0 Comments