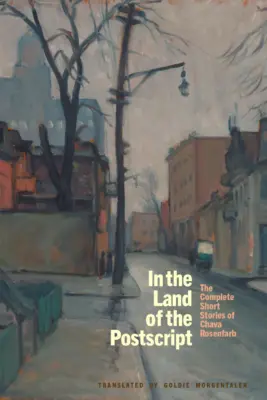

Though Canadian Yiddish writer Chava Rosenfarb died in Lethbridge over a decade ago, her influence and oeuvre continue to take shape in important ways. The appearance of a new generation of Polish-language critics and translators who are drawn to work like Rosenfarb’s, which they view as an important part of their own Polish literary heritage, has led to a resurgence of interest in her fiction, poetry, and memoiristic writing. This is also in part due to the energy and creativity of her translator and daughter Goldie Morgentaler, whose efforts have resulted most recently in the publication of a new collection of Rosenfarb’s short fiction, entitled In the Land of the Postscript.

In the Land of the Postscript

The Complete Short Stories of Chava Rosenfarb

Chava Rosenfarb

Translated by Goldie Morgentaler

White Goat Press

$18.95

paper

299pp

9798987707838

Holocaust experience is conveyed differently in “Edgia’s Revenge,” a long, almost novelistic story narrated by Rella, a former kapo (concentration camp guard), whose “one good deed was to save the life of Edgia,” as Morgentaler puts it in her introduction to the collection. Rosenfarb is on fresh territory in offering a post-Holocaust story from the point of view of a kapo, Jewish or not. Recalling her arrival in Canada following the war, Rella considers how “commemorations, memorial evenings, remembrance ceremonies were attended by masses of people. Books began to appear on the subject of the Holocaust […] But nobody tried to get to the bottom of the particular tragedy of the Jewish kapos.”

“Edgia’s Revenge” provides an important portrait of survivors’ lives in the immediate postwar years, a subject that is under-discussed. Like other stories in the collection, it depicts the ways that Canadian survivors remade their lives, with Rosenfarb’s favoured focus on Montreal and how the city received them. Iconic streets like Esplanade Avenue, with its view of parks and the mountain, placed European Jewish newcomers in a remarkable downtown setting, punctuated by the city’s lighted cross atop Mount Royal. The cross, to them, is both a banal marker and a symbol of Jewish marginality.

Morgentaler’s introduction to her mother’s stories is succinct and detailed. She offers a picture of pre-World War Two Canadian Yiddish culture, to which postwar writers like her mother were forced to adapt. The introduction conveys Rosenfarb’s own wartime experience, a personal narrative that underwrites her fictional renderings of survivors’ lives. This aspect of Rosenfarb’s work – her urge to fictionalize what she could simply present as personal experience – is her distinctive contribution to Holocaust literature. The stories’ shared themes, rendered through rich character portraits, offer a detailed portrayal of the postwar scene in which survivors are “haunted by their Holocaust experiences, but haunted in all the diverse and individual ways that make one human being different from another.”mRb

0 Comments