Kevin Lambert’s Querelle of Roberval is a vibrant storm of gossip and myth. Lambert has plucked his protagonist from Jean Genet’s 1947 Querelle de Brest and set him down in small-town Quebec as a labourer at a sawmill whose workers are attempting to unionize. Leaving Montreal after growing alienated from his friends with loftier and more boring ambitions than his – condominiums, scholarships – Querelle moves to Roberval and becomes the witting object of desire of the town’s men and boys – both the young queer men who flock to his apartment for sex at night, and their homophobic fathers – while a strike at the sawmill becomes increasingly contentious.

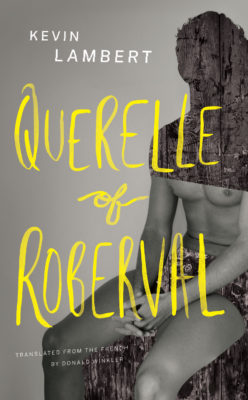

Querelle of Roberval Biblioasis

Kevin Lambert

Translated by Donald Winkler

$22.95

paper

200pp

9781771963541

Querelle of Roberval was originally published in French (winning Lambert the 2019 Sade prize in France), and translated to English by Donald Winkler. The language of the novel is rich and evocative, a compliment to both Lambert’s and Winkler’s instincts for poetry. Lambert displays his linguistic skill equally in images of the erotic and the abject, in a prose that entices and disturbs at the same time. This effect is most compelling in his descriptions of physicality and embodiment, in which he maps the contours of sex and violence and how the two bleed into one another. His sinister mythology is peppered with reminders of our current context that lace the heavy poetic language with a welcome sense of humour. When Querelle seduces young men in a desperate attempt to “seek refuge in his own abjection”, he finds them on Grindr, and when one character is impaled on a spit and roasted over an open flame to be devoured by the others, he is slathered in Costco barbecue sauce, thinned with wine and water.

Tensions in Roberval amplify as both the sawmill picketers and their opponents – their bosses, as well as the loggers whose own income depends on the sawmill’s operation – express their desperation with growing frenzy. When Querelle becomes the target of small-town gossip concerning the whereabouts of a young boy missing from the community, he becomes the centre of the conflict, an antiheroic martyr through which the people of Roberval exorcise their own turmoil.

Lambert relies more heavily on the surreal as the novel progresses, a shift that sustains the escalating violence and desensitizes the reader to the increasingly grotesque imagery. The suggestion, at the beginning of the novel, that the sawmill owner has spiked his workers’ coffees with Javex bleach, pales in comparison with the depravity to come. By the end, Lambert faces us with infanticide and necrophilia and dares us not to flinch. These scenes are no longer shocking because he has disoriented reality in an embrace of myth and theatre. The townspeople of Roberval morph into a chorus, singing an a capella dirge when the novel’s climactic murder occurs. Scenes of sexual assault or exploitation are written as sacred, but equally depraved, religious rituals. In the words of Lambert’s narrator, who describes the movement of a rumour through the small town: “at every twist in the tale […] there is a heightening of alarm and a crescendo of the voice, and a few more blooms are added to the bouquet of blood-soaked images.” Lambert’s own blood-soaked tableau is a gory, sensual, and provocative exploration of sex and violence, and their potential to redeem lives that have been deemed, for one reason or another, not worth living.mRb

0 Comments