We live in such a hyperconnected world that the notion of a pop culture phenomenon remaining confined to one place is all but obsolete. But there are still a few out there.

Shigeru Mizuki is a living icon in Japan, to the point where an entire street in his birthplace, Sakaiminato, is given over to bronze figures representing characters from his work, and the nearest airport has been renamed in his honour. If you’re not Japanese, though, or a serious manga cultist who has learned the language, you’ll be forgiven for not having heard of him. The 91-year-old cartoonist’s first publication in English came just two years ago, when Drawn & Quarterly brought out a translation of his remarkable World War II memoir, Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths.

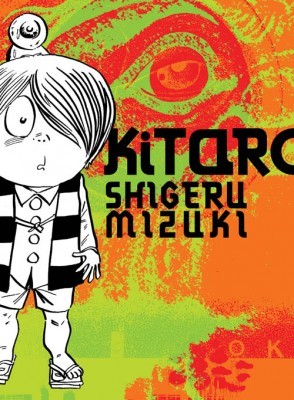

Kitaro

Shigeru Mizuki

Drawn & Quarterly

$26.95

Cloth

396pp

9781770461109

For manga newbies, indeed for anyone not accustomed to a lot of fantasy in their reading, this may all sound like at least one contrivance too many, but Mizuki renders his parallel world with such complete assurance that all such reservations quickly fall away. It helps that his settings are very much those of a recognizable Japan, drawn with a stylized realism that counterbalances the fantastic yokai goings-on perfectly. Among many other things, this book constitutes a tour of Japanese cultural touchstones. One of those is baseball, and Mizuki gives the sport its due in “Monster Night Game,” in which a player discovers a magic bat and soon has to choose between home-run omnipotence and his soul.

Elsewhere, “Ghost Train” follows a pair of Tokyo hipsters as they get definitively disabused of their smug disbelief in monsters; “The Great Yokai War” functions as a (possibly ironic) protest against the encroachment of Western pop monsters into post-war Japan. We’re reminded that these stories, for all their otherworldly timelessness, date from 1967 through 1969, and that the spirit of protest sweeping the western world at that time had very much reached Japan and had a voice in Mizuki and Kitaro; the stories’ scepticism about violence as a problem-solver is all the more powerful coming from an artist who lost an arm as a soldier.

A final note: this book honours traditional Japanese practice in being designed to be read from right to left, both on the page and within individual panels. I mention this only because I still occasionally meet people reluctant to take on the reading of manga because they think the whole “backwards” thing will trip them up. Trust me, within three pages or so it feels perfectly natural. Besides, what better way of encountering a new world than by reading in a new way?

0 Comments