Kuessipan, we are told on the dedication page, means “your move” or “your turn” in the Innu language. Not having read the book yet, we don’t know whose turn it is. But we know already that this will be an Innu story, and those who read on are rewarded with an intimate view of a unique community, situated in a geographical and historical place unknown to most of us non-Innu, although both the geography and the history are deeply connected to our own.

This is not a traditional plot-driven novel; its “arc” is rather a tiny segment that trails filaments back into the past and, as it grows along the pages, into the future. Rather than follow a single protagonist along a plotline that leads from A to B, this story accumulates in thin sheets, sometimes only a couple of paragraphs long, that gradually build a picture that surrounds the main figure, a young woman who rarely shows herself as “me” or “I” but who allows us to see her life in its details.

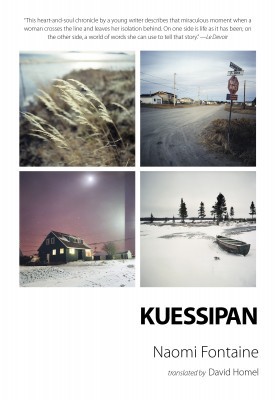

Kuessipan

Naomi Fontaine

Translated by David Homel

Arsenal Pulp Press

$14.95

Paper

90pp

978-1-55152-517-4

Fontaine’s descriptions of the poverty and dislocation of life in Innu country will not surprise anyone who reads the news, but in contrast to most of those news stories, her layered images of Innu life are full of human depth, including also struggle, pride, joy, and love. It is not a romanticized view, but contextualized, with an intelligence that keeps the story engaging.

In the end, it is a story of strength and of hope, which are intimately entwined. The hope is for the future, in the sleeping body of our heroine’s baby son, and the strength is from the past: “the life she had chosen now, that she had borrowed from her ancestors.” She draws power from her sense of herself, amplified by her people’s long history, fortified by the life she is making now, in which she is, in her own home, the woman of the house.

So whose turn is it? It is the turn of Nikuss, “my son,” who will draw his own strength from the land and the past of his people. He has his work cut out for him. He will know “that even the earth can be deformed by human grasping, the water sullied by contempt for everything that does not bring riches.” But a baby is nothing if not hope embodied, and he will “bring comfort,” he will “see the beauty of the world,” his “laughter will be the echo” of his mother’s hopes. He will stand with her “by the shore and the tides.”

Like all good stories, Naomi Fontaine’s Kuessipan ends with a beginning. mRb

Beautifully described.