After making a splash in the alternative comics world last year with Photobooth, a delightfully idiosyncratic history of the titular machines and the author’s own obsession with them, Montreal-based artist and illustrator Meags Fitzgerald returns this fall with Long Red Hair, a new memoir about childhood, female friendship, and coming of age queer. Fitzgerald’s books are beautifully drawn in a realistic style that accentuates the surfaces of everyday objects and environments. Always attuned to the larger cultural perspectives suggested by their personal narratives, both Photobooth and Long Red Hair are examples of how graphic memoirs can transcend stories of the self in order to bring vibrant visual life to the marginal and the unexpected. Busy between her book launch and a trip to the Small Press Expo in Bethesda, Maryland, Fitzgerald found time to discuss her new book with me over email.

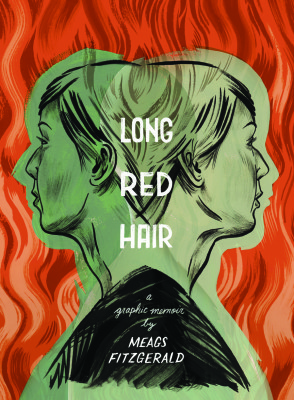

Long Red Hair

Meags Fitzgerald

Conundrum Press

$17.00

paper

88pp

9781894994958

Meags Fitzgerald: As a child I struggled with reading and writing, I loved stories but even little chapter books were daunting and felt inaccessible. From a young age, I was a strong drawer and so my interest in comics felt very natural. I’ve been writing and drawing my own stories since I was about six years old. Now, as an adult who reads a lot of books, my favourites all happen to be graphic novels. I think that’s because my mind operates in a very visual way, I just connect with the material on another level.

FBK: In comparison with the episodic nature of your new memoir Long Red Hair, your previous book, Photobooth, is both more traditionally literary and linear, and is closer to being an illustrated personal essay than it is to being a comic in the ordinary sense. Did that shift occur organically as part of your developing practice, or was it more a question of what felt right for each narrative?

MF: It’s true, I use very different narrative devices in each book. The shift was to serve the stories that are told in Long Red Hair. I wanted the narrator to have less of a presence and for the story to unfold more organically in conversation. For example, there’s only about a dozen speech bubbles in all of Photobooth (a 280-page book) but it’s the primary textual tool used in Long Red Hair.

FBK: I sense the influence of such authors as Alison Bechdel and Ariel Schrag on Long Red Hair, and in addition to writing graphic memoirs, both of those artists are of course thematically preoccupied with queer identities and coming-out narratives. In fact, there seems to be an entire sub-genre of coming-out narratives that has appeared in comics over the last few years, and I’m wondering if you think there is something about comics that lends itself to these types of stories?

MF: I believe that things that live in the fringes of society and popular culture have a way of finding each other. For that reason I don’t think it’s a coincidence that queer narratives lend themselves to the comics medium. From the beginning, alternative, underground comics have tackled sexuality in an honest and raw way. There seems to be a new wave of creators using the medium this way, likely in part because of the influence of Bechdel’s Fun Home. Admittedly, it was a huge inspiration to me.

FBK: More broadly, I’m interested in your thoughts about the relationship between comics and autobiography. And from your own perspective, why memoirs?

MF: I work in several disciplines, so aside from making comics and illustrations, I also perform at live storytelling events where I tell autobiographical stories. My relationship to the audience at these events feels very different from my relationship to readers (when I do get the opportunity to meet them in person at comic conventions). The difference hinges on a public vs. private dynamic. The connection you can form with someone after they spend 10+ hours reading about your life is deep. I’ve had some incredibly powerful meetings with readers and received emails that were so thoughtful that I was brought to tears. I haven’t experienced a bond like that yet from my work on stage. A book is an intimate object and I believe that enhances the truthfulness of the narrative.

FBK: At one point in Long Red Hair, you mention that when playing dress-up with your friends as an adolescent, “we were one way at school, and another version of ourselves entirely after sunset.” This is followed by a sequence where you and your friends play with Ouija Boards, read each other’s palms, and watch movies such as The Addams Family, The Craft, and Practical Magic on VHS. Could you elaborate a little on what you mean by this – what exactly is this “other version” of yourself, and how does it relate to the book’s overall preoccupation with femininity and what it means to be a girl and young woman in the culture?

MF: As a young girl, you first learn to understand your body through the perspective of older, white men. The media plays such a dominant role in the lives of our culture’s youth. I think that as a child, my friends and I were drawn to entertainment related to the occult because witch characters were singular and strong. A lot of other films made in the late 1980s to mid-1990s had very few or no female characters. Think of the first Toy Story film: all of the toys except the porcelain figurine, Bo Peep, are male. That sends a message to girls. I believe we were drawn to the supernatural and macabre because it felt a little forbidden and a little defiant. It’s empowering to break the rules (even if it’s only a perception). At a sleepover, where there are no rule-makers, we were free from the expectations of how little girls ought to behave. We knew we weren’t made of porcelain.

FBK: Finally – and just because I’m curious: In Photobooth, you mention several times that the paper stock used for colour photos is no longer being made, and that at the time of the book’s writing it was projected to be used up by summer 2015. Do you know if this has happened? Have we reached a point where the last colour photobooth picture has been taken?

MF: It hasn’t happened yet but it’s in the works. This summer, the last remaining chemical photobooths were removed from many Canadian cities. In Montreal, we’re lucky, because the company that operates all the booths in Canada is based here, so they’re leaving them for a bit longer. In the last few weeks I noticed that some have disappeared from metro stations but the most popular ones will probably last until the winter holidays. I knew it was coming but my heart truly aches every time I pass a spot where a photobooth used to be. mRb

0 Comments