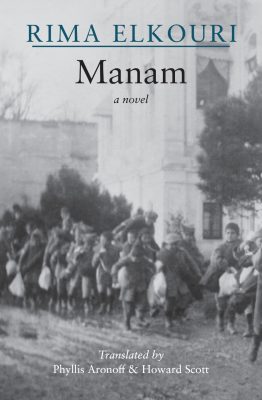

Manam, the first novel by well-known Montreal journalist Rima Elkouri, is layered, surprising, and transformative (and effectively team-translated by Phyllis Aronoff and Howard Scott in an empathetic English version). Elkouri, whose tenure as a columnist at La Presse began on the eve of the attack on the Twin Towers, has written about the complexities of what falls under the rubric of “Arab,” and about her own complicated identity. Among other trials and travels, the Armenian side of her family was decimated and dispersed during the genocide that left more than 1.5 million dead. This novel explores and renders that often unspoken violence.

Léa, a schoolteacher, decides to visit her late grandmother’s birthplace in present-day Turkey, “a country founded on forgetting,” both as a way to piece together the particulars of her family history and to search for the tendrils of belonging that the children of immigrants yearn for. She hires a local guide, a handsome film- maker whose genealogy was also muddied by the slaughter: like many others in the region, his ancestors were Armenians who converted to Islam, whether by force or to survive – people horrifyingly referred to as “the remnants of the sword.” The narrative follows Léa as she meets with locals who share threads of where she comes from and why her family left. Léa stitches together her own sorrowful infertility, memories of her grandmother, accounts of how her family managed to survive the Turks’ carnage, and letters from her grand- mother’s twin brother who stubbornly and poetically refuses to leave present-day, war-ravaged Syria.

Manam

Rima Elkouri

Translated by Phyllis Aronoff and Howard Scott

Mawenzi House

$20.95

paper

144pp

9781774150443

What most anchors the narratrix to her family’s past is sense memory: the smell of Aleppo soap, its painstakingly specific fabrication from olive oil, laurel berries, and saltwort ash; the description of cleaning out the grandmother’s house after her death; the familiar sweetness of the kleichas baking in a shop she wanders into, which leads to the baker sharing her own mother’s experience of about the summer of 1915.

Many of the stories Léa hears evoke the long and bewildering tug- of-war that inches toward healing: “Whether you’re the descendant of victims or murderers – or even of both, which is probably the case for the majority of us – don’t we need, now more than ever, to hear stories of resistance?” That resistance, and especially the unimaginable courage and resilience of survivors, is the central, pulsing wound in the novel. The title means “dream” in Arabic, but its fictional development here is the stuff of nightmares: Manam is also the name Elkouri invents for the Turkish town that was the site of one of the bloodiest massacres.

The book echoes with the peculiar, choking recitation of those who recount things that can scarcely be spoken. There are sentences in books like this that you read, and then you reread them, and you never forget them but you can also never repeat them. Whose words are they to speak? Whose wounds? Whose healing? Whose blade? Yet you have to read this book; I think we have to scream this book: as Léa knows, “worse than death is forgetting.”mRb

0 Comments