Martha Wainwright regrets not a word printed in her first work of autobiographical writing. From the other end of the phone line on a precariously sweltering spring day while sitting under the shade of a tree in the yard of her Outremont home, the renowned singer-songwriter – now notable author – shared that the titular regret was the publisher’s proposal from the onset, providing more of an abstract tuning key than any formal constraint during the book’s gestation. This memoir formed an almost mythical chapter of its own in the author’s life, a formalized lark that drew itself out over the span of seven years – a number that is loaded not with superstition, but with the significant wisdom of Martha’s hard-earned experience. (There are many Wainwrights and only one Martha, so I’ll refer to her here by her first name.)

The arc of her life story is loosely drawn in the memoir’s first few pages, a summary that gives a few hints as to her path’s main vicissitudes: feeling unrooted in faith and place, the complexity and sting of big truths about her life, and a habit of eschewing expectations. Sure, reading of the trappings of a well-known and beloved showbiz family can give a thrill here and there. The magic in this work, though, is not imbued by whichever legendary figure she gets to encounter by virtue of connections she is born into, but by the clarity of her language and the effortlessness of her prose. “It’s the gift of a performer to be sensitive to her public,” she believes, and that sensitivity has translated as unvarnished sincerity and candidness on the page, as on stage. She writes as she speaks, not as she sings, though both preserve a somewhat confessional intimacy without being eminently quotable or pithy.

Reluctant to mimic or appropriate another’s style, Martha spent little to no time doing literary research. “I happened to have read Joan Didion’s A Year of Magical Thinking at one point, and really admire her direct and powerful style. But I can’t even begin to try to write like her.” Any groundwork was mainly spent attending to her relationships, ensuring that they were depicted in ways that honoured the other’s own sense of an event or experience. “We remember things differently and feel them differently, too,” she writes. That care is palpable and earnest, even and especially in the ways she adores her brother Rufus, while also not sparing their less appealing exchanges or traits, which in turn invites the reader in as confidante. The care she has carried out through the pages leaves us variably cherishing even the most complex and difficult of characters.

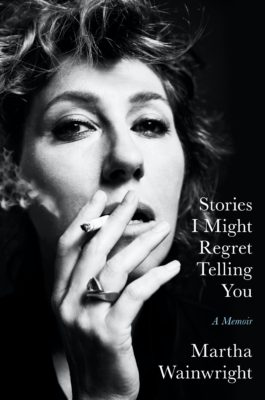

Stories I Might Regret Telling You Penguin Random House

A Memoir

Martha Wainwright

$34.95

cloth

256 pp

9780345815088

Whereas Martha’s relationship with Rufus reads as having more grounding stability borne of mutual admiration and delight, withstanding whatever competitive and comparative impulses arise from their dual sibling and collaborator relationship, her connection with her mother is explored with a poignant depth and sharpness reserved for that bond alone. Kate led a creative life guided by often unspoken but firm feminist ideals, bound by the paradoxical though not impracticable tension between self-affirmation, independence, and nurturance. Martha’s impulsiveness that marks her way of moving through the world is clearly related to her mother’s shrewd vivacity, which the matriarch did a great deal to inspire in her children, embarking on tours with the whole family in tow, a spontaneous cycling trip to see her daughter in New York, and flights across an ocean to support the harrowing first days of Martha’s own journey of motherhood.

Kate’s exacting expectations of her children to respect their talents while carving their own path led to some heated moments, particularly when colliding with Martha’s sporadic hedonism. Kate’s brief jabs of judgement are recalled with the keenness and the clarity of maturity. And yet there’s a grace in the light that Martha casts on their differences, as though she never shied away from learning the lessons their relationship has yielded.

Even though many pages are suffused with enough emotion to bring readers to tears, through several heart-rending episodes spanning her mother’s protracted fatal illness through the eventful birth of her first son, Martha never gets (as she calls her songwriting) “gory in all its details.” We are far from Knausgaardian meticulousness, while still guided to glean what makes meaning and keeps her alive. “I can really sit in sadness, as you might have guessed, but I can get out of it pretty easily, too, often by singing,” she writes. The performer knows how to steer the ship in a way that makes her public want to be in it.

Now a little older and wiser, an accomplished artist and engaged mother, this feels like the right time for Martha to have put her unsentimental pen to paper in generous expression of her most prominent influences. But what remains once one has revealed a life in memoir? “The telling of my story may make room for something else, perhaps for my family, my children, my partner, and what we’re going to do together in this crazy world,” she says. Still fulfilled by her craft and her relatively new commitment to tending a venue near her home, the charming and burgeoning Ursa, she feels like she still has a lot of work left to do to keep supporting herself and her family.

If song remains a way for the Wainwrights and McGarrigles to build a supportive way of life by which many members abide, this narrative of Martha’s life and its revelations do nothing to weaken its buttresses. We close the book quite in awe of how the branches of the family tree have yet to really buckle in the sway of time, owing to something Martha does a good job of illustrating: the instinctual dance of interconnection between family, passion, and commitment.

Where are we left in the end, after entering life having “barely made the cut”? “This book has helped me feel a little more comfortable with my worth. I’m good enough,” Martha shares in our talk. One thing is certain, there’s much more she can do with her formidable writing talent. If she was “broken but running” in her youth, she has hit an enviable stride of being flawed but thriving. And readers should be here for it.mRb

0 Comments