May Our Joy Endure begins with one long sentence devoted to the air, which sweeps the talk taking place on the sidewalk up, storey by storey, until it reaches a luxurious residence on the sixty-third floor. Continuing its passage through an elegant birthday party attended by Montreal’s political and cultural elite, the air jingles the crystals of an immense chandelier and “dislodges fetid words reeking of alcohol and meat” before settling in next to Céline, “indisputably the best-known Québécoise in the world.” Céline – not Dion but Wachowski – is a billionaire architect in her late sixties, with a popular Netflix show, Hollywood friends (to her, they’re simply Meryl and Sigourney), and impressive buildings all over the world bearing her vision.

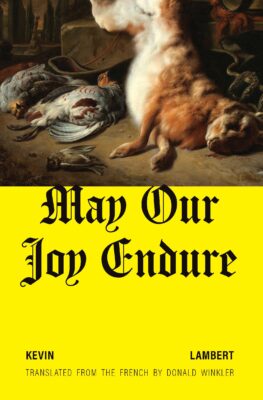

May Our Joy Endure

Kev Lambert

Translated by Donald Winkler

Biblioasis

$24.95

paper

296pp

9781771966207

Before long, Céline becomes the figurehead of the whole Webuy mess, thanks in no small part to the publication of two New Yorker articles inveighing against her so-called ethical approach to architecture. Protests follow. Unhappy shareholders revolt. The board members of Ateliers C/W tell Céline she has to go.

Céline’s career and reputation suffer, but she’s still a billionaire. The third and final section of May Our Joy Endure brings Lambert’s critique sharply into focus, indicting the fickleness of public opinion, the hollowness of “cancellation” when it comes to the affluent and powerful, and the inadequacy of protest that targets individuals over systems.

The novel takes its title from a passage from Marie-Claire Blais’ These Festive Nights, translated by Sheila Fischman, which also serves as one of the epigraphs. Lambert is unmistakably Blais’ heir, adopting a similar style composed of sweeping, maximalist sentences, an abundance of comma splices, and a slippery, shifting point of view that considers any character, no matter how minor, worthy of the spotlight. (Translator Donald Winkler deftly recreates these engaging stylistic idiosyncrasies.) Consider the overnight cleaner who offers us her reflections on Bruegel the Elder, who depicted “a world that cannot be reduced to a single perspective, an ultimate truth.” Like Bruegel and Blais, Lambert uses a large cast of characters to depict society’s complexities. His gaze is oceanic, homing in on individuals and zooming out to the systems within which they operate. He’s attuned to the flow of capital, gossip, and desire, writing about money streaming into bank accounts and shell companies, about businessmen arranging hook-ups with boys and thus “enhancing the global transmission of sperm being leached out in unsavoury byways.”

At the party that opens the novel, Céline joins her friend Dina in an impromptu song made up of one sentence, one wish: “May our joy endure.” Others join in. The song emerges from Dina’s recognition that while life is fragile and fleeting, she and her guests have experienced love and beauty. Lambert’s narrator then tries to quantify “the precise number of lives putting Dina’s birthday into play,” from the well-heeled guests to the servers, coat-check staff, and chauffeurs. Even transcendence can’t transcend the realities of class. As Céline later observes, “Proust was wrong in imagining the decline of a social class that is thriving more than ever.” To the question “What endures?” the novel has a ready answer: the dominance of the rich.mRb

0 Comments