Emma, Lama, Sally, and Louise are young women trying to make satisfying lives for themselves. Emma, a Tunisian immigrant and engineer, is rebuilding her life after divorcing her psychologically abusive husband. Lama is studying business administration, excited about her future but frustrated with her shallow mother and sisters. Sally is a Pakistani-Canadian whose recent turn to a stricter religious practice has created tension with her hardworking immigrant parents. And Louise, daughter of a French-Canadian mother who rebelled against the oppressive Catholicism of her own childhood, is in nursing school and, although it takes her a while to admit it, in love.

What they have in common is that they are all young Muslims. Mirrors and Mirages offers a refreshing glimpse into the inner lives of a cohort not yet well represented in Canadian fiction. In fact, believers of any faith are thin on the ground in CanLit, and the effort these characters make to balance their individual beliefs and the demands of their families and the culture around them is central to the story Monia Mazigh wishes to tell.

Mazigh is known for her battle to free her husband, Maher Arar, who suffered rendition and torture in 2002. Mazigh chronicled that experience in a non-fiction book, and subsequently ran for the NDP in Ottawa. Mirrors and Mirages feels very much as if it springs from the same well of social commitment, giving Canadian readers, Muslim and non-Muslim alike, rare images of the diversity of Muslim women’s lives in this country.

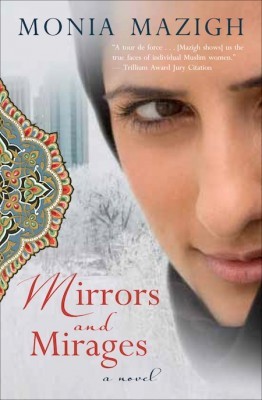

Mirrors and Mirages

A Novel

Monia Mazigh

Translated by Fred A. Reed

Arachnide

$22.95

paper

258pp

978-1-77089-359-7

If that sounds didactic, it is. Mirrors and Mirages feels rather like a well-meaning lecture, an impression reinforced by its stodgy tone. Mazigh tells us that Sally’s father chose that name for her because it was “a modern, upbeat name that would help her fit in.” (Not since it peaked in popularity in the 1930s.) Or take the young man who has a crush on one of our heroines, who describes himself as “the boy from your class.” It sounds like Dick and Jane. These are not the hip young hijab-wearing women I see all around me.

The book also seems to suffer from neglect. Mazigh’s writing is not well developed; she makes mistakes that a more experienced writer would avoid, such as over-writing (“The row houses were all two storeys: a ground floor and a second floor”) and using dull abstractions rather than scenes or details that would enliven the text. There are inconsistencies throughout – in one scene a character is standing to pray and in the next moment she is described from another point of view as kneeling, forehead to the floor. In another scene, “winter’s hardly here,” but then there is “spring sunlight.” A character comments on a phrase that someone else thought, but never spoke aloud. It is a shame that these errors were apparently never edited out, either in French or in English, weakening the reading experience and undermining Mazigh’s very good intentions. mRb

0 Comments