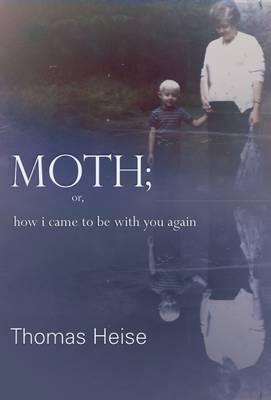

With Moth; or, how I came to be with you again, Thomas Heise has written a deeply moving account of loss, migration, and memory that blurs the line between poetry and prose. An associate professor in McGill’s English department, Thomas Heise has published numerous articles, a book on the interrelations between urban space and narrative (Urban Underworlds, 2010), and a book of poetry (Horror Vacui, 2006).

Moth; or, how I came to be with you again

Thomas Heise

Sarabande Books

$15.95

paper

165pp

978-1-936747-57-3

According to its preface, Moth was composed originally by hand in German, stored and forgotten in the back lining of a suitcase, then found and eventually translated. Its narrator applies the principle of Joe Brainard’s I Remember in compiling lists of memories rendered discrete, each sentence beginning with “I remember…”: “I remember when I touched my sleeping mother’s hair, it sparked in my hands and I thought she was inhuman…”; “I remember a strange family had taken me into its arms, welcoming me “home.”

Other souvenirs of a solitary adolescence, set in an atmosphere of exquisite gloom, recount strange meditative acts: “Unblinking, I would count backward from zero into an imaginary and negative realm of decreasing absolute magnitude where I hoped I might discover a pinprick, a small eye-tear in the fabric into which I could slip a gaunt arm.”

Throughout, there is a sense of surplus that’s closely related to the inexhaustibility of the narrator’s memory and imagination. The book’s dominant syntax (long periodic sentences chaining subordinate clauses to subordinate clauses) strongly contributes to the effect, which feels like a process of breathless accumulation. Wry, laconic remarks sporadically counterpoint long sentences: “A perfect world is right around the corner, and far, far away.” “The moment the chimp recognized he was human, he began to paint over the mirror.” “I wrote these words too, but they were unsatisfying like the colour grey or lamb.”

Such subtle turns of wit temper the book’s melancholy with understated, ambivalent humour. This combination is one of Moth’s many treasures.

Whether Heise’s somnambulist narrator salvages some notion of home by the book’s conclusion or whether his sense of anguish and deracination persist without cure, we don’t know. Three quarters of the way in, some kind of breakdown occurs, and it is very moving. The title word “moth” plainly suggests metamorphosis; and it’s possible that the narrator’s depression has lifted in the time intervening between the composition of Moth and the writing of its preface. The question rests perhaps on the therapeutic value of art, by which the convalescing poet has “come to be with us again.”

Jacob Siefring is a freelance literary critic and blogger living in Ottawa. He received M.A. in English and M.L.I.S. degrees from McGill University. His website is bibliomanic.com.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks