Ever since publishing her first critically acclaimed book, The Philistine, in 2018, Leila Marshy has felt herself walking a new path. “It signalled the beginning of, I would say, my literary life, and it signalled a different stage in my social literary life,” she tells me during our interview on Zoom. A life, it seems, marked by a resounding success as a new author. The Philistine, a deeply queer story of reconnecting with oneself and one’s culture, was shortlisted for multiple prizes and translated to French only a few years after its debut. The Arabic translation is due out this year.

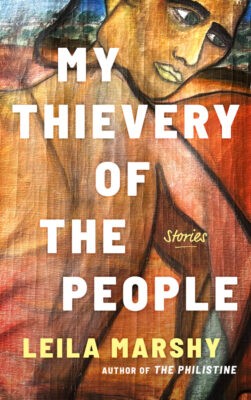

Marshy’s new book, a collection of short stories entitled My Thievery of the People, marks a new milestone in her literary career, although she feels a different connection to the book than she did to The Philistine. “The Philistine was a labour of love,” relates Marshy when asked about her new book in our interview. “It was my first book. I worked on it for a long time, on and off, I kept dropping it. But I had faith in it, I loved it… I was really close to it.”

My Thievery of the People Baraka Books

Leila Marshy

$24.95

paper

168pp

9781771863773

Marshy might be referring to the strong heteropatriarchal figures that appear as villains in this vastly diverse universe of short stories. A universe that varies delightfully in form – from journalling about the last days at a job after being fired, to a “How to” guide to internal collapse, to the mythical resistance of two women woven through history, to suspense and murder mystery. “I like to have fun with different forms,” she says, “and a story takes the form it needs. I like the challenge of having to create momentum and a lot of these stories have that.” Marshy’s fun is incredibly contagious.

My Thievery of the People opens on two strangers at a book event who are having a hard time connecting: “I really wanted that to set the tone. From a distance, it’s two people amiably talking, but up close, it’s two extremely traumatized people putting on their masks and not really communicating at all.”

This conjures, of course, our universal feelings of loneliness and alienation in big tech’s capitalist apocalypse, which 2025 seems shaping up to be, to put it mildly. This is especially daunting when you are a part of a community that has been historically oppressed and discarded, relegated into otherness. A sentiment Marshy knows all too well: “That’s my default place in the world that I’ve often papered over and kind of minimized in my life. But being outside and lonely and feeling vulnerable and misunderstood, you know, is also kind of human condition stuff.”

These feelings could seem pessimistic, and although Marshy’s characters and narrators are often cynical (in the best way), they embody a deep sense of agency that compels them, and hopefully by extension, the readers, to act. “My entire motivation is to question the power structure,” says Marshy. “I think colonialism in all its forms has been a horrible blight on the planet. It’s our responsibility as individuals, as artists even, to hold up the collective and help people resist erasure.”

My Thievery of the People helps us believe 2025 might not be that bad after all, and that big tech and other power structures should fear us. Marshy’s figures of power are fundamentally fragile and could crumble in the face of disaster, or fate, or chance. She highlights her female character’s resilience in one of the best stories of the collection, “1001 Nights in Palmyra’s Bed.” Its protagonist Noha struggles with her brother Ali’s royal-like return home after years of working abroad. Her destiny is tied with Queen Zenobia’s, a mythical queen who famously resisted Roman siege. “It’s, again, a story of resistance. It’s about personal occupation, but it’s also the story of Palestine. It’s like: resistance by any means necessary. In the end, resistance wins. Maybe it’s a kind of revenge fantasy.” Yet Marshy doesn’t really like the word revenge for its narrowness and implied violence. Retribution is closer to what she means, or justice.

Just like in The Philistine, Egypt makes multiple appearances throughout My Thievery of the People, becoming a character Marshy has loved ever since she lived there in her twenties. “Egypt helped me understand a few things about the world. Colonialism, poverty, the privilege of foreigners, the way in which Egyptians are stuck, get stuck, stay stuck. You can be absolutely brilliant and talented but there are too many structural and social things keeping you down.” Marshy’s connection to Egypt is also intertwined with the larger Middle East and her own Palestinian heritage. The latter doesn’t, however, often emerge in her writing, taking instead the shape of activism and community action in her day-to-day life. “I didn’t live in Palestine the way I lived in Egypt, and so the stories don’t just spontaneously arise. I could create one but then it wouldn’t feel authentic. I don’t want to shoehorn my Palestinian-ness. I mean, I lived in Egypt because I am Palestinian. It’s all connected.”

Marshy’s sophomore book, My Thievery of the People, signals that the writer’s literary path is only entering its bloom. Since last summer, she has taken up the role of fiction editor with Baraka Books. She feels right at home with the editorial vision of this Montreal-based publisher. “We share a need for political meaningfulness in the books we publish and write. Not all publishers have that mandate.”

Her current project? A non-fiction anthology of contributions about how Palestinians and their allies have been punished and scrutinized in Canada over the past year for their engagement, coming out this fall. And she has much more to celebrate: The Philistine has been optioned and is being made into a movie!mRb

0 Comments